Ancient Footprints to Tiny 'Vampires': 8 Rare and Unusual Fossils

Move over, dinosaurs!

Untold numbers of fossils representing billions of years of geologic history are preserved around the planet, and though large and heavy dinosaur bones tend to be the most visible examples, fossils can take many forms.

Fossils can represent microscopic creatures, animals with no bones at all, preserved internal organs, and traces of skin, hair and feathers. They can even offer evidence of ancient animals' behavior in impressions of footprints or burrows, or as individuals trapped in amber — snapshots of life in scenes from the distant past.

In addition to offering tantalizing glimpses of animals that went extinct millions of years ago, fossils also reveal the ancient world they inhabited. Each precious find is another tiny piece in the vast puzzle of Earth's geologic history, and helps scientists to understand how life on this planet evolved and changed over billions of years.

Here are a few examples of spectacular finds that offer a window into Earth's past, and help scientists understand the remarkable animals that lived long ago.

Oldest on Earth

Scientists recently unearthed the oldest fossils ever found: layered structures created by microbes 3.7 billion years ago, preserved in ancient rock in Greenland. Their discovery pushes back the earliest evidence of life on Earth by approximately 220 million years. [3.7-Billion-Year-Old Rock May Hold Earth's Oldest Fossils]

The fossils were found in metamorphic rocks that were subject to intense underground heating and pressure, so the finding will likely face scrutiny over whether the observed structures arose from natural causes or if they indeed have biological origins, according to scientists.

Tiny "vampires"

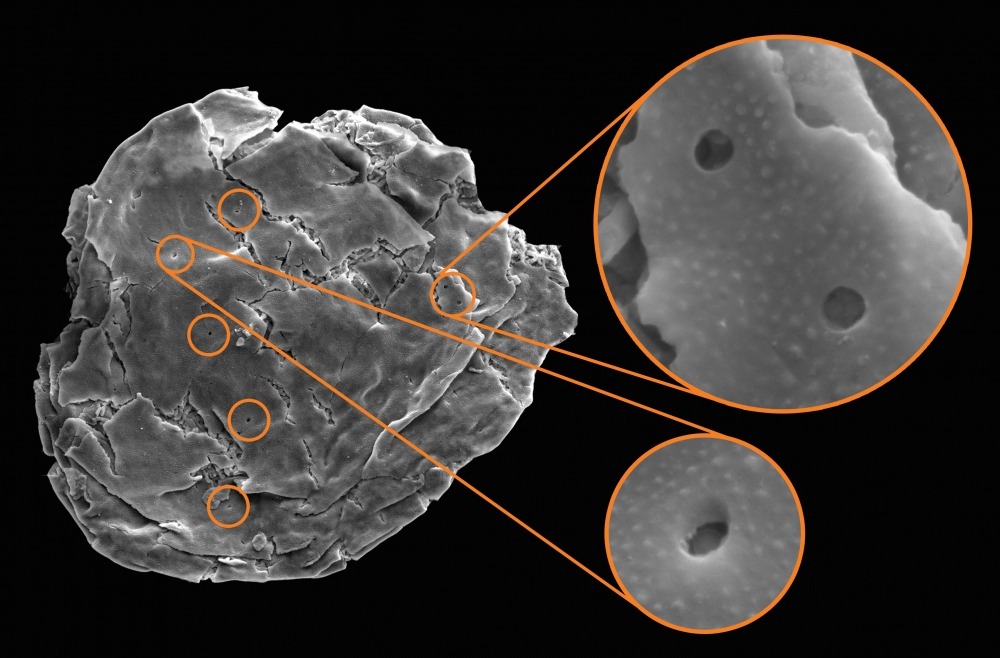

Microscopic fossil structures perforated by tiny, circular and half-moon-shaped holes show that even ancient microbes had predators. Discovered in Arizona's Grand Canyon, these preserved, shell-like pods that protected single-cell organisms were punctured in several places — most likely by a miniscule creature in search of a meal, according to a study published in May 2016 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"It would be hard to explain these very distinct holes, except through predation," according to Melanie Hopkins, an assistant curator of invertebrate paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Hopkins, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that this is the oldest known evidence of predatory behavior, dating back approximately 750 million years ago.

Study author Susannah Porter, an associate professor of paleobiology at the University of California in Santa Barbara, wrote in the study that this type of predation — which she described as "vampire-like" — is similar to that of certain amoebas alive today, which may be modern relatives of this ancient predator.

Oldest nervous system

The oldest and best-preserved nervous system to date belongs to a fossilized arthropod that looked like a shrimp in a fancy helmet.

Discovered in what is now South China, Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis lived 520 million years ago, and was described in a study published in March 2016 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Running along the length of the ancient animal's segmented body was a visible central nerve cord, studded with nerve tissue masses arranged along its entire length. The preservation was so good that researchers were even able to detect individual nerve structures.

Fossilization typically preserves only hard structures such as bones, teeth, exoskeletons or shells. But the location where these arthropod fossils were found is well-known for conditions that are ideal for preserving soft tissue. The animal's carcass likely was buried in fine sediment and had little exposure to oxygen; this allowed the internal organs to fossilize rather than decay, and preserved them in exceptional detail.

An intermediate pterosaur

The fossil pterosaur Darwinopterus astonished paleontologists — for the first time, they saw a creature whose body plan included features associated with two separate pterosaur groups that lived during time periods separated by millions of years. The earlier pterosaur group had long tails, while the group that emerged later had large heads.

Darwinopterus, however, had both.

"Darwinopterus is thought to be the bridge between those two groups," paleontologist Mark Witton, who was not involved in the study describing the pterosaur, told Live Science.

According to Witton, Darwinopterus — which lived 161 million years ago and was described in a study published in October 2009 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B — not only answered important questions about how pterosaurs evolved, it offered vital insights into the workings of evolution itself.

"You imagine evolution working in a fairly minimalist way — it makes a few changes here and there, and then over time you gradually go from one form to another," Witton said. "What Darwinopterus showed us is that in the case of these pterosaurs at least, that didn't happen at all."

Based on the evidence of the Darwinopterus fossil, scientists learned that the head and neck anatomy associated with the later group of pterosaurs evolved first, and evolved quickly, Witton explained. Darwinopterus resembled the later group of pterosaurs from the shoulders up, but the back end of its body was "classic long-tailed pterosaur," Witton told Live Science.

Oldest vertebrate brain

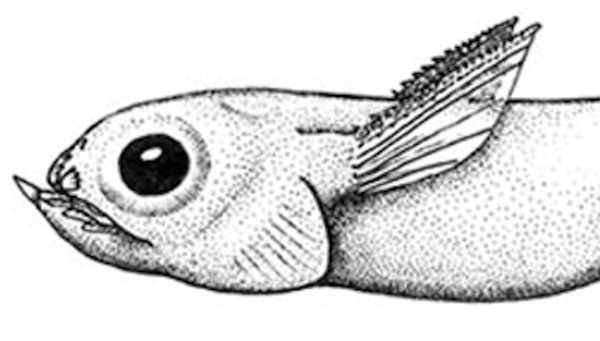

The oldest example of a fossil brain from an animal with a backbone belongs to a bulging-eyed fish that lived 300 million years ago and was a relative of modern fishes in the shark family.

Fossilized brains are unusual, to say the least. Organs fossilize only rarely, and the brain's tissue is especially soft and delicate. Prior to this discovery, described in January 2009 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paleontologists gathered what information they could about brains in fossil animals from impressions that the brains left behind on fossilized skull material.

Scientists used computed tomography (CT) to scan the tiny object — which measured a mere 0.3 inches (7 millimeters) in length — and reconstructed it in 3D. Well-preserved details in the brain revealed a large vision lobe, and optic nerve extending to the braincase.

Insect warfare

Amber tombs preserve the bodies of ancient ants and termites, offering a glimpse into the behavior and social structure of insects that lived millions of years ago.

The ants, some of which are locked together forever in mortal combat, are 99 million years old, and the termites in amber date back 100 million years — the oldest termite specimens found to date. Different body adaptations in the termites are described in a study that was published in February 2016 in the journal Current Biology, and identify them as soldiers or workers, hinting that even millions of years ago — during the early stages of termite evolution — termite social structure included highly specialized roles.

Animals entombed in amber really do seem to be frozen in time, retaining the shape and color of their bodies as they appeared in life. Because the sticky tree sap traps them so quickly, animals can be captured in the middle of interactions that scientists can interpret millions of years later, to understand how they lived.

Ancient footprints

Fossil bones suggest what an animal may have looked like on the inside, but individual fossil footprints or collections of prints — known as trackways — provide a view of a fully-fleshed animal foot as it pressed into wet sand or mud. Preserved prints left behind by an early human ancestor 1.5 million years ago offer clues not only to the shape of their feet but how they used them, suggesting they walked much like modern humans.

The tracks were found in Kenya in 2009, and were described in a study published in July 2016 in the journal Scientific Reports. The impressions featured a pronounced arch, a big toe that lay parallel to the other toes, and a round heel, similar to human feet, but were far too old to be human. Researchers determined that the prints were made by Homo erectus, an older hominid lineage.

Analysis of the prints revealed that they were created by stepping motions that were identical to those used by Homo sapiens — with the inner ball of the foot and the first two toes applying most of the pressure.

Further investigation of how the footprints were grouped suggested that males congregated together, hinting at some form of sex-specific social behavior.

Colored feathers

A fossil of a tiny dinosaur with four wings provided scientists with a rare glimpse of how those wings may have looked in life, when they were covered with feathers.

The dinosaur, known as Microraptor, was about the size of a modern pigeon and lived in southeastern China about 130 million years ago. Researchers described the fossil in a study published in March 2012 in the journal Science. The scientists analyzed the traces of feathers preserved in the fossil, and looked at miniscule structures called melanosomes that lend color to feathers.

The arrangement of Microraptor's melanosomes told scientists that its feathers were black, and that they were probably 120 million years old, making this specimen the earliest fossil evidence of iridescence in feathers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.