Tiny 'Vampires' Put the Bite on Amoeba Prey 740 Million Years Ago

When movie vampires strike, they leave behind telltale marks in the victim's neck — puncture wounds that show where they sank their fangs. More than half a billion years ago, similar evidence was left behind in fossils by predators that were a lot smaller than your average Hollywood bloodsucker.

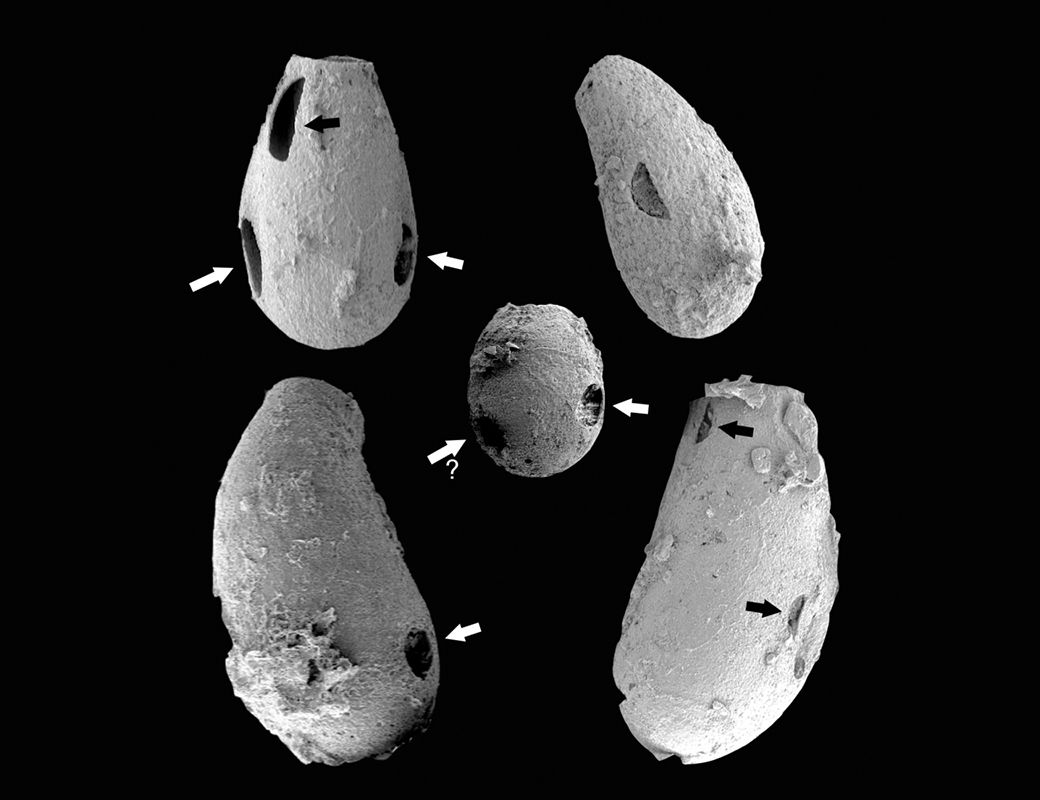

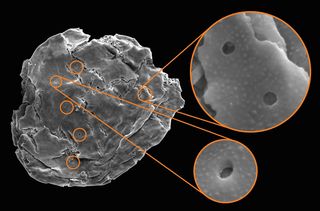

Recently, scientists discovered amoeba fossils perforated with circular holes that were likely made by microscopic predatory creatures 740 million years ago. The holes showed where a single-celled predator drilled through its amoeba prey's protective cell wall to consume the material known as cytoplasm that lies inside, according to a new study.

This is thought to be the oldest evidence of predatory behavior in eukaryotes — the group of organisms with complex cells that includes all plant and animal life on Earth — and is the earliest known evidence of predation in the fossil record. [Ancient Footprints to Tiny 'Vampires': 8 Rare and Unusual Fossils]

Fossils too small to see

The fossils, which measure 75 to 150 micrometers (about 0.003 to 0.006 inches) in length, were found in the Grand Canyon basin, in what is now Arizona. But hundreds of millions of years ago, this was a shallow seabed with warm, calm waters that hosted untold species of single-celled organisms, according to the study's author, Susannah Porter, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Finding fossils of early life that are too small to see with the naked eye is challenging, to say the least, Porter told Live Science. Researchers studying life from this era — known as the Precambrian, which covers all geologic time on Earth up until about 600 million years ago — look for certain types of rocks that are likely to hold fossils. That rules out metamorphic rocks that have undergone dramatic structural changes, or coarse-grained rocks that could allow water to flow through them, carrying bacteria that would consume organic material and prevent an animal from fossilizing.

Fine-grained rocks, however, "are like a tomb," Porter said. "They're not very porous, and they seal the fossils up."

Even so, only about 5 percent of the samples that scientists collect contain fossils, she added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's a little bit of a gamble," Porter said. "You could come up with nothing, or you could hit the jackpot."

A familiar sight

The holes that Porter saw in the fossils reminded her of similar holes left by contemporary amoeba predators with the ghoulish name Vampyrellidae amoebae, which she encountered during earlier research related to fossils from this group, she told Live Science.

Another possible cause — bacteria breaking down and eating the cell wall after the animal had died — couldn't explain the patterns and the precision of the circular holes, Porter said.

"With microbial degradation, you would expect to see larger, more widespread perforation that would show further breakdown and consumption of the wall," she said. "I never saw that. It looked like something was trying to go through the wall to eat what's inside."

In some species of modern vampire amoebas, the animal extends part of its body as an appendage called a pseudopod, to engulf part of the prey's cell wall. Then, it produces an enzyme that cuts a ring through the wall, allowing the amoeba to lift up a circle of the protective wall "like a manhole cover," Porter said. Once the hole is made, the amoeba can insert its pseudopod to scoop out the cytoplasm inside, or absorb the cytoplasm as it oozes out of the hole, much like vampire bats lap up the blood that wells from puncture wounds in their mammalian victims.

But there are still important pieces missing from this ancient story of predation at the microscopic level. The prey species that the so-called vampires fed on is yet to be identified, Porter said. However, the fossils can still help scientists understand the diversity of single-celled life during the Precambrian that was just a precursor of the vast diversity of more complex forms that would emerge during the Cambrian period, about 540 million to 350 million years ago.

"This is giving us a first glimpse of the diversification of complex cells — eukaryotes — rather than bacteria and archaea [a group of single-celled organisms with no nucleus]," Porter told Live Science. "It shows us that our ancestors had started becoming important in terms of their role in ecosystems and their diversity on Earth."

The findings were published online May 18 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.