The Feejee Mermaid: Early Barnum Hoax

The Feejee Mermaid (sometimes spelled Fiji Mermaid and FeJee Mermaid) was a hoax promoted by P.T. Barnum during the 1840s. It was the most famous of several fake mermaids exhibited during the 19thcentury. The Feejee Mermaid was exhibited in New York, Boston and London. Its whereabouts after 1859 are uncertain.

The Feejee Mermaid and other hoax mermaids had the upper bodies of apes sewn to fish tails, according to "The FeeJee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History" (Cornell, 1999), by Jan Bondeson. The Feejee Mermaid was probably made from an orangutan and a salmon.

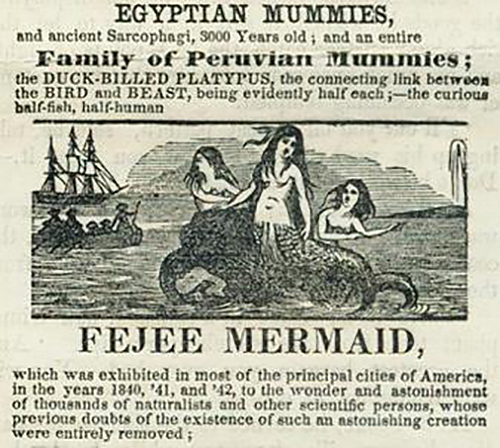

Unlike images of mermaids in folklore and popular culture, such mermaids were unattractive, often described as hideous. In his autobiography, Barnum described the mermaid as "an ugly dried-up, black-looking diminutive specimen, about 3 feet long. Its mouth was open, its tail turned over, and its arms thrown up, giving it the appearance of having died in great agony."

The Feejee Mermaid was instrumental in Barnum's success as a master showman. Not only was it hugely popular, it is emblematic of Barnum's ingenious plots to generate interest in his curiosities. "Barnum concocted quite an elaborate scheme to expand the curiosity into 'mermaid fever,'" said Adrienne Saint-Pierre, curator of the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Origins in Asia

According to Steven C. Levi, in "P.T. Barnum and the Feejee Mermaid," an article in the journal Western Folklore, the mermaid was likely created in the early 1800s by a Japanese fisherman. Levi suspected that the fisherman created the mermaid as a joke, while Alex Boese of the Museum of Hoaxes writes that such figures were used in religious practices in Japanese and East Indian villages.

Barnum's Feejee Mermaid was probably sold to a Dutch merchant during the 1810s. At that time, the Dutch were the only Westerners permitted to trade with Japan. After Commodore Matthew Perry opened trade between Japan and the rest of the Western world in 1853, many more fake mermaids appeared on the scene. Though these mermaids did not resemble the beautiful creatures described by Hans Christian Anderson, Shakespeare and others, the craftsmanship of the Asian mermaids was so fine that many Westerners were taken in anyway, according to Bondeson.

The mermaid goes to England

After being acquired by the Dutch, the mermaid went to England. The Dutch merchant ship sank but an American captain named Samuel Barrett Eades rescued the crew and the mermaid. According to Bondeson, Eades was so fascinated by the mermaid that be bought it from the Dutch in January 1822. He had to sell his ship to pay the $6,000 price.

Eades needed travel money, so he exhibited the mermaid in Cape Town. There, it was met with fanfare. A prominent English missionary wrote a much-circulated newspaper article that attested to the mermaid's validity.

In September 1822, Eades arrived in London with the mermaid. He set up a display at a coffeehouse with the mermaid under a thick glass dome. According to Bondeson, it was called the "Remarkable Stuffed Mermaid" and was the talk of the town throughout the fall. Every day, hundreds of people paid the 1-shilling price to see the mermaid.

Soon after arriving in London, Eades, who seems to have believed that the mermaid was real, invited two prominent naturalists to examine it. They proclaimed it fake, but Eades consulted other, less-knowledgeable naturalists, who said it was legitimate. This pleased Eades, who, in an act of great hubris, eventually claimed that one of the prominent naturalists, Sir Everard Home, had also stated that the mermaid was genuine. Home was furious and got several respected publications to announce that the mermaid was a fraud. This, Bondeson writes, was the beginning of the end for Eades' success with the mermaid.

The rush of articles denouncing the mermaid also implied that the public was gullible. Attendance at the mermaid exhibit fell off and in January 1823 the coffeehouse closed. Over the next few years, the mermaid toured England but it was not overly popular, as news of its fakery had circulated the country.

Meanwhile, it came to light that Eades had not been the only owner of the ship he sold to pay for the mermaid. The other part-owner brought legal action and the mermaid was ultimately declared a ward of the chancery (a ward of the court), which inspired several political cartoons. It nevertheless seems that Eades was able to keep exhibiting it, according to Bondeson.

Eades was ordered to pay back the co-owner of the ship. According to Boese, Eades sailed the seas for the next 20 years trying to pay off the debt but never succeeded. When he died, the mermaid went to his son. It was his sole inheritance.

Mermaid fever in New York

After its initial fame in England, the mermaid existed in relatively obscurity for nearly 20 years, according to Bondeson. Then in the early 1840s, Moses Kimball, proprietor of the Boston Museum, met with Eades' son and bought the mermaid. In 1842, Kimball traveled from Boston to New York to meet with his friend, P.T. Barnum, who had recently purchased a museum in the city. He suggested that they work together to exhibit the mermaid.

"Between the two of them they engineered quite a story preceding the public presentation of the Fejee Mermaid," Saint-Pierre told Live Science. "Barnum leased the mermaid from Kimball. The plan was cleverly crafted to incite, at first, just a little interest from the press, with made-up letters to the papers from people in distant states who claimed to have met a Dr. Griffin from London and had seen his amazing creatures, including the mermaid. Interest escalated when Griffin 'arrived' at a hotel in Philadelphia before his supposed return to London, and the press had to get a look."

But Dr. Griffin was not who he said he was. He was Levi Lyman, who, according to Steven C. Levi, had worked with Barnum on a hoax in 1835. But "Dr. Griffin" proved pivotal in the mermaid's success.

At the time, new animals from around the world really were being discovered, said Saint-Pierre. Dr. Griffin showed the public other unusual animals, like the platypus, which seemed to offer proof that he was a naturalist and that the mermaid was real.

Additionally, Dr. Griffin and Barnum appeared to have a public tiff, which aroused interest. Barnum wanted to exhibit the mermaid at his new American Museum, but Dr. Griffin refused. Barnum said he had already created publicity materials for the mermaid, and, supposedly unable to use them, gave them to the New York media to use. This made him look generous, but was really a devious way to promote the mermaid, said Saint-Pierre. It also angered the newspaper staffs, for each had been told they were the only outlet getting the publicity materials. Instead, on Sunday, July 17, 1842, identical advertisements for an exotic mermaid appeared in all the papers. Interestingly, the advertisements showed beautiful mermaids with the torsos of voluptuous human women — completely different than the Feejee Mermaid's appearance. But given the mermaid's success, the public didn't seem to mind.

Dr. Griffin's letters, the Philadelphia appearance and the advertisements had New Yorkers desperate to see the mermaid. Following his and Barnum's plan, Dr. Griffin agreed to exhibit it for a week at the New York Concert Hall. Crowds flooded the exhibit, where the fake naturalist gave lectures stating that all land-dwelling animals have counterparts in the ocean (sea horses, sea lions, etc.), so it only followed that sea-humans would exist, according to Boese.

After a week at the New York Concert Hall, Dr. Griffin "generously" agreed to let Barnum show the Mermaid at his American Museum. Attendance at the museum tripled.

"The idea of first showing the Fejee Mermaid at a venue other than the American Museum was a brilliant strategy because Barnum knew his reputation was tarnished, or 'suspect,' that people had not forgotten the Joice Heth hoax from a few years before," said Saint-Pierre. (The Joice Heth hoax involved claiming a woman was 161 years old when she was, in fact, in her 70s.)

"That had been his first real venture into showmanship, and one he looked back upon in later years with regret for how it was handled, Saint-Pierre continued. "But at the time, Barnum was smart to realize that if all he did was simply show the mermaid in his museum there would have been a lot of scoffing and doubt, and perhaps only a little interest."

Barnum exhibited the Feejee Mermaid in New York with great success for one month. After that, he decided to send it on a tour of the Southern United States. His uncle, Alanson Taylor, was to care for it.

A controversial tour

Taylor lacked his nephew's showmanship and press navigation skills. In Charleston, Taylor found himself at the center of a feud between two local newspapers; one attested to the mermaid's genuineness, while the other adamantly claimed that the mermaid was a fraud and that the people of Charleston were idiotic to see it. Taylor was harassed publicly. The skeptics were led by the Rev. John Bachman, who threatened to destroy the mermaid.

The rental lease between Barnum and Kimball stipulated that Barnum would take upmost care of the mermaid, so this threat worried Barnum. Though he initially tried to use the controversy to generate press and keep the tour going, Barnum ultimately realized that Taylor was not up to the task. The mermaid was returned to New York.

Saint-Pierre noted that this episode illustrates an important aspect of Barnum's development as a showman. He was able to recognize when the mermaid had had her run in a town. "I think Barnum was realizing he had crossed the line perhaps a few too many times with the mermaid scheme. He speaks about regretting it when he was older, though he did show other mermaids during the years of the American Museum."

Additionally, Saint-Pierre said, the Charleston incident helped cement his friendship and business relationship with Kimball. When the mermaid was under threat, Barnum went out of his way to rescue it and adhere to the lease.

What happened to the Feejee Mermaid?

Upon its return from Charleston, the Feejee Mermaid was again displayed at Barnum's American Museum in New York. According to Boese, in 1859, Barnum took the mermaid on tour to London, where it again proved a popular attraction. When Barnum returned to the United States, the Feejee Mermaid took up residence at Kimball's museum in Boston. That is its last known location.

In the early 1800s, Kimball's museum burned down. It is unclear whether the Feejee Mermaid was destroyed in the fire or rescued. According to Bondeson, some sources report that it was retrieved from the debris. In 1897, Kimball's heirs donated a fake mermaid to Harvard University's Peabody Museum. It is still there today, but it is still unknown if it is the original Feejee Mermaid.

"The Peabody has no solid documentation that their mermaid was the one that Barnum rented from Moses Kimball," Saint-Pierre said. "Kimball did exhibit mermaids at later times, so it could be that the mermaid is a later one. … It could certainly be argued that its rather good condition indicates it was a later version, not as well travelled as the original Fejee Mermaid."

The mermaid at the Peabody also looks significantly different from the Feejee Mermaid described by and pictured in Barnum's autobiography. There, she is depicted mounted vertically, "with a large head and pendulous breasts," said Saint-Pierre. "The Peabody's mermaid is very different, being horizontal, like a fish, and with a small head and no breasts." The Barnum Museum has a replica of the Feejee Mermaid as depicted by Barnum, which was made for a TV documentary.

The Feejee Mermaid's legacy

Though hoax mermaids existed before the Feejee Mermaid, its success and the opening of Japan made them far more common in the curiosity landscape of the 1800s. According to Boese, the term "Feejee Mermaid" came to be something of a generic term for "hoax mermaid." Nevertheless, Barnum's original Feejee Mermaid was a bigger success and captured the public imagination in a way other hoax mermaids did not. It was and continues to be regularly referenced in popular culture.

Some of its power probably comes from the important role it played in the development of Barnum's career as "America's Greatest Showman." Saint-Pierre said, "A large measure of Barnum's success was due to his understanding of his audiences, discerning what they wanted and finding clever ways to promote what they wanted, and finding ways to get people to want what he had to offer them. The challenges that came about with the mermaid scheme undoubtedly set the stage for Barnum's later successes with Tom Thumb and Jenny Lind [and Jumbo the elephant], because he realized the immense value of promoting in advance, and that it had to be carefully choreographed, not done at random."

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.