Great Debate: Should Organ Donors Be Paid?

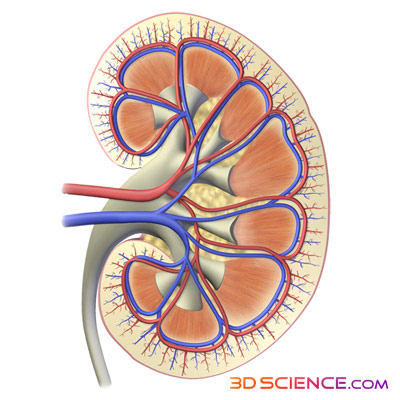

The recent arrest of a businessman accused of buying and selling kidneys in the United States, a scandal unearthed on July 23 as part of the New Jersey corruption investigation, has drawn attention once again to the ever-growing organ shortage in this country. Over the years, the number of people waiting for an organ in the U.S. has soared upward, increasing from 31,000 people in 1993 to over 101,000 today, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, the non-profit organization that keeps track of all the transplants in the U.S. As the shortage grows, the dilemma remains, how can the number of donations be brought up to meet the need? Some think this supply-and-demand problem could have a financial solution — provide incentives to donors. Of course, selling organs in the U.S. is against the law. The National Organ Transplant Act, passed in 1984, states that human organs cannot be exchanged “for valuable consideration,” meaning something of monetary value. But for years, members of the transplant community have debated the idea of providing incentives to organ donors, such as tax credits or even direct payments. However, some fear that these types of incentives could lead to an unregulated market for organs and is not worth the risk. While implementation of incentives is likely far off, the issue has divided the transplant community, and no clear consensus exists. Perhaps the greatest amount of discussion for financial incentives surrounds kidney donation. Not only is the need for this organ the greatest — about 80,000 people on the UNOS list are candidates to receive a kidney — but it is one of the few organs that can come from a living donor (while people have two kidneys, they need only one to function normally). Since donations from the deceased alone are not likely to meet the demand for kidneys — last year there were about 8,000 deceased donors, which results in 16,000 kidneys, only 20 percent of the total number on the waitlist for kidneys — some have focused their attention on ways to increase the number of living donors. Take Away “Disincentives” Since some people actually end up losing money when they give an organ, one idea is to take away any financial obstacles that might hinder someone from making a living donation. While some people who favor these types of incentives will not go as far as to say donors should benefit financially, they do agree that donors should not be put at a monetary loss for their altruism. For example, in the rare case that donors experience complications from the procedure, they may have to pay for lifelong medical treatment. Others may have to pay for their travel to and from the hospital, or they may lose money when they take time off work after the procedure. The National Kidney Foundation is in favor of covering these types of donation-related expenses, says Dolph Chianchiano, the vice president for health policy and research at the foundation. For instance, they are supporting state and federal legislation to create tax credits for living donors that would reimburse their out-of-pocket donation costs, he says, even if it doesn’t increase donations. “The main reason [we support reimbursement] is that it’s the right thing to do for the living donors,” says Chianchiano. “But one would hope that it would alleviate some concerns that potential living donors might have.” Providing initiatives to remove financial disincentives “may increase living donation,” says Dr. Francis L. Delmonico, a transplant surgeon and medical director of the New England Organ Bank in Newton, Mass. There are 49 million people in the U.S. without health insurance, says Arthur Matas, a surgeon and director of the University of Minnesota’s Renal Transplant Program. And providing them with reimbursements for medical care or even health insurance in case they change jobs and are not covered due to a preexisting condition may ease their worries about being a donor. The American Society of Transplant Surgeons also supports getting rid of disincentives, and they even have a program that provides aid to living donors who have lost money as a result of their donation. However, donors need to apply for the funds, and the program has only reimbursed about 500 donors in the U.S., according to Delmonico. Money For Kidneys? Imagine if people were not just reimbursed, but actually paid for their kidneys. Some people think that a regulated system could be put in place in which true financial incentives — ones that result in financial gain — are provided to donors. This incentive could be a cash payment, or something less direct, like lifetime health insurance. One of the biggest fears with introducing financial incentives is that it might lead to an organ market and create a situation in which the rich could exploit the poor for organs. “Once you insert monetary gain into the equation of organ donation, now you have a market. Once you have a market, markets are not controllable, markets are not something you can regulate,” says Delmonico. “The problem with markets is that rich people would descend upon poor people to buy their organs, and the poor don’t have any choice about it.” However, others feel that such a system could be overseen by transplant professionals who would screen donors and decide if they are healthy enough to donate, says Dr. Benjamin Hippen, a nephrologist. This system would be drastically different from the organ trafficking schemes that have arisen in other countries such as India and Pakistan. In these unregulated systems, the middleman who purchases the organ for a recipient has no interest in the health of the donor. “The sort of thing that I’m thinking about changes the incentives so that there’s a focus on the propriety of safety [and] on the transparency about the risks to the person exchanging their kidney,” he says. Extremely poor people could also be excluded from the system, says Hippen. Poverty is associated with a high risk of kidney disease, and thus an exchange involving a very poor donor would not benefit either party, he adds. Removing poor people from the system would also prevent this group from being exploited by those with more money. However, Hippen does not consider fear of exploitation as a reason to omit the poor from this system with incentives. “I don’t think the mere fact of being poor renders poor people incapable of making decisions that materially affect their lives,” he says. In this system, the government would pay for the incentive, regardless of its form. The cost of keeping a patient who needs a kidney on dialysis is so expensive — around $65,000 to $75,000 per year — that it would be in the government’s interest to pay for a transplant as well as an incentive, says Hippen. “The transplant pays for itself versus dialysis after about 18 months,” he says. And kidneys would be allocated in the same way they are now for deceased donations — through UNOS. This organization has a contract with the government to manage organ procurement and transplantation, and people who need organs are matched through the UNOS system. “That’s a fairly efficient and medically sound way to allocate kidneys,” says Hippen, who thinks such a system would also work for live donations. This set-up would mean that the rich and poor would have equal access to kidneys, says Hippen. “There wouldn’t be any discrimination [regarding] the recipients’ socioeconomic status; kidneys would really be allocated according to medical criteria and not by how much money the recipient has.” Decreasing the organ shortage in the U.S. would also reduce the market for organ trafficking in other countries, says Hippen. “The reason that organ trafficking flourishes is because it’s economically supported by wealthy countries where there’s a disparity between the demand for and supply of organs,” he says. However, those opposed to financial incentives argue that the risk of slipping from incentives into a market is too big to take. “We’ve just been though two years of complete economic collapse at the inability to regulate markets because people cut corners, cheat [and] are not forthcoming,” says Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. “And there’s no reason to think a market in organs would work any differently.” Additionally, there is a concern that certain religious groups would be turned off by the idea of financial incentives, says Caplan. If individuals in these groups stopped donating organs, the organ supply could actually decrease. And even if incentives are put in place, they may still not persuade many people to provide their organs for transplant. “There’s not a lot of evidence that what is stopping people from giving kidneys when they’re alive or when they die is money.” says Caplan. While almost everyone is in agreement that the disincentives need to be removed, there is great debate about whether or not to provide financial incentives, with people passionate on both sides, says Matas, of the University of Minnesota. If financial incentives were ever put in place, they would most likely first need to go through pilot trials to test out different systems. They could be carried out in a few regions in the country and conducted like research studies, with both a trial and follow-up period. However, before any studies could take place, the National Organ Transplant Act would need to be lifted for that area. “Right now we’re not even close to there yet,” says Hippen. Meanwhile, the waitlist problem remains. “As we have these debates about what to do, the waiting list gets longer and the waiting times get longer,” says Matas. “We need a radical change to our approach.”

This story is provided by Scienceline, a project of New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

- Video: Organ Repair

- Body Quiz: The Parts List

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.