Zika Can Cause Birth Defects in Monkeys Too

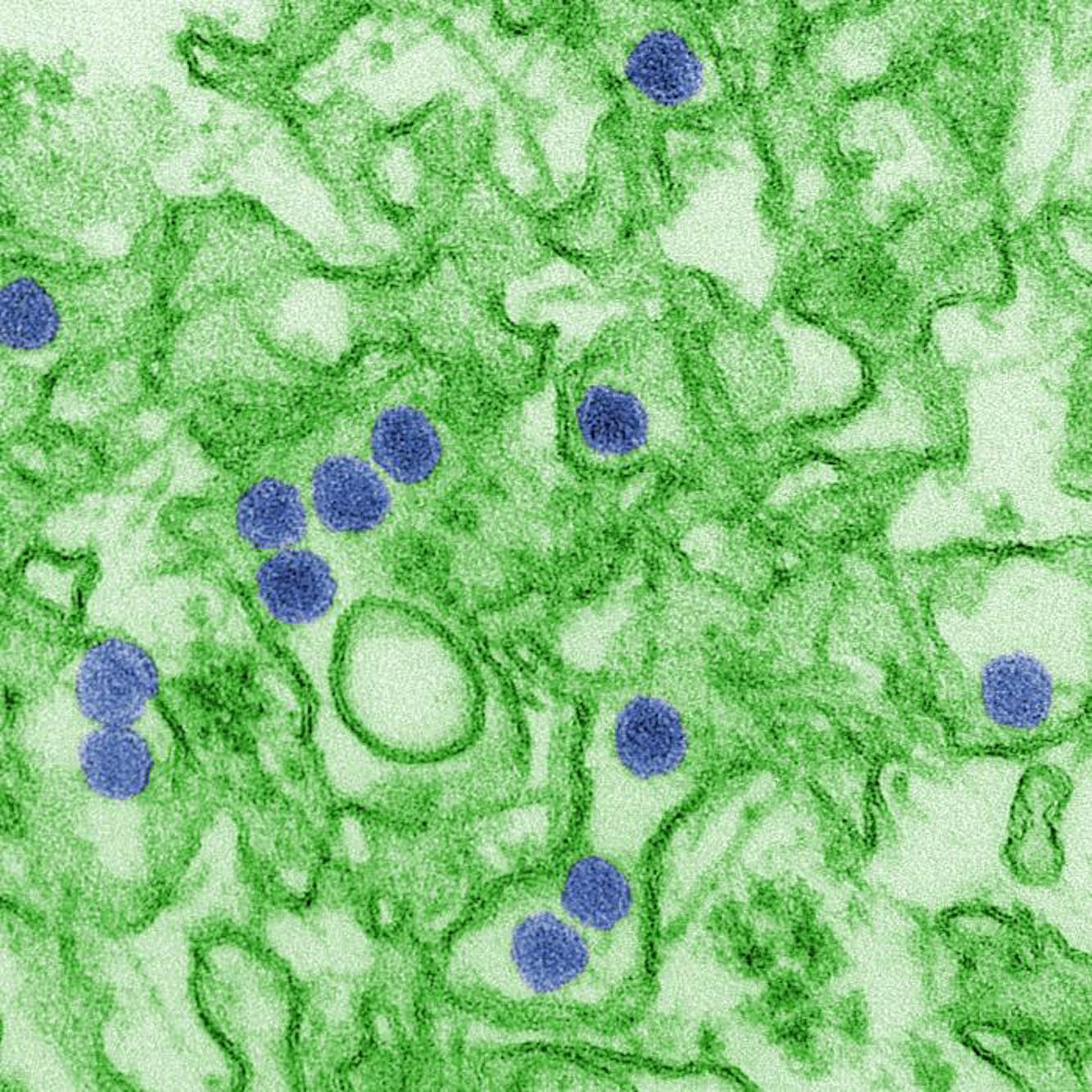

Some monkeys can contract Zika virus in the womb and show signs of brain damage similar to those seen in human babies, according to a new study.

The findings mark the first time that a monkey has shown signs of "congenital Zika syndrome" — the range of health problems linked with Zika virus infection in the womb. The results suggest that researchers may be able to develop a model of Zika virus infection in monkeys that could help with the development of vaccines or other approaches that would help prevent birth defects caused by Zika, the researchers said.

Researchers have been trying to develop a model of congenital Zika syndrome in nonhuman primates (such as monkeys) because pregnancy in nonhuman primates more closely resembles human pregnancy, compared to pregnancy in other animals such as rodents. However, in a previous study of pregnant monkeys infected with Zika, the virus did not appear to make its way into the fetus's brain tissue, as it does in humans.

In the new study, the researchers used a different species of monkey, called a pigtail macaque, and used a slightly higher dose of Zika virus for infection.

The researchers infected a pigtail macaque with Zika when it was in the third trimester of pregnancy. Signs of brain injury to the fetus occurred quickly — within 10 days of infection, the researchers said. The fetus developed brain lesions and showed signs of slowed brain growth as well as injury to parts of nerve cells called axons. The researchers also found evidence of the Zika virus genetic material in the fetal brain tissue. [Zika Virus News: Complete Coverage of the 2016 Outbreak]

The findings show that a Zika virus infection during pregnancy "has the capacity to result in fetal brain injury in a pregnant pigtail macaque," the researchers wrote in the Sept. 12 issue of the journal Nature Medicine. This animal model "may have significant utility for testing novel vaccines and therapeutics to prevent the congenital [Zika virus] syndrome," the researchers said.

More studies are needed to better understand how the virus causes injury to the brain, they said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.