How a Hidden TB Infection Caused One Woman's Infertility

A woman living in New England who had trouble getting pregnant eventually discovered that her infertility was due to a cause not typically seen in this country: tuberculosis.

The 31-year-old woman had been trying to get pregnant for a year and a half, but had not been able to conceive. She appeared healthy; she exercised regularly, rarely drank alcohol, had never smoked, was not overweight and had regular periods, according to a report of her case from doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital. She had been born and raised in Nepal and had also lived in India before moving to the United States five years earlier.

Nine months before the woman went to Massachusetts General Hospital, an exam at another hospital showed that she had blocked fallopian tubes. These kinds of blockages prevent sperm from meeting an egg, and therefore cause infertility. Infections can result in blocked fallopian tubes, but so can a condition called endometriosis.

A common solution for women with blocked fallopian tubes who want to get pregnant is in vitro fertilization (IVF). So the woman and her husband went through two rounds of IVF, in which doctors mixed the woman's eggs and the man's sperm in lab dishes to make embryos, and then implanted the embryos in the uterus.

But IVF didn't work. Each time, the embryos failed to implant in the uterus. [Conception Misconceptions: 7 Fertility Myths Debunked]

The doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital then tested the woman for several infections that are known to affect fertility, including chlamydia and gonorrhea, but the results were negative.

They also performed a biopsy of the woman's endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, which revealed several granulomas. These masses of tissue are usually produced in response to an infection, but can also result from exposure to a foreign substance, such as talcum powder.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

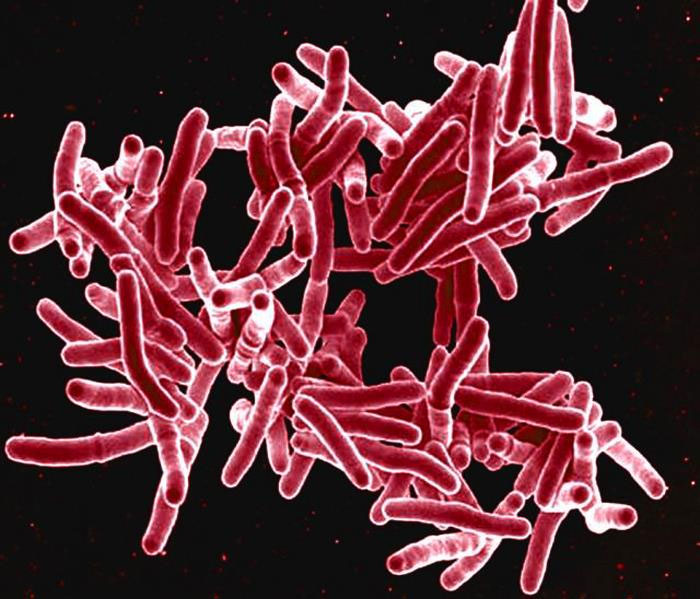

The woman's doctors then suspected she could have a tuberculosis (TB) infection of the uterus lining, because the illness is known to cause granulomas in this tissue. As a child, the woman had received the BCG vaccine, which reduces the risk of TB; however this vaccine does not always prevent a TB infection, the report said.

She did not have any other symptoms of tuberculosis, either, such as coughing or chest pain. But in many people, the infection is "latent," meaning the immune system keeps the bacteria under control and people don't show symptoms and aren't contagious, according to the Mayo Clinic.

It's uncommon to see tuberculosis as a cause of infertility in the United States, and doctors do not routinely screen for it, said Dr. Richard Legro, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health sciences at Penn State University College of Medicine, who did not treat the patient, but was involved in writing her case report. The woman's TB would likely have gone undiagnosed if she had not sought treatment for infertility, Legro said.

Although people tend to think of TB as primarily a lung disease, it actually "can affect most organ systems, so you always have to be aware of it," Legro said.

Tuberculosis is rare in the United States, but common in Nepal and India, the report said. Genital infections with TB are a common cause of some types of infertility in developing countries; a 2008 study of 140 Indian women seeking IVF found that 25 percent had genital TB. And among the women whose infertility stemmed from problems with the fallopian tubes, 50 percent had genital TB, the study found.

Genital TB can be difficult to diagnose, in part because patients can have varied symptoms or no symptoms at all, according to a 2011 paper. Many women who are eventually diagnosed with the condition first went to the doctor because of infertility, the paper said.

The New England woman tested positive for genital TB and underwent treatment with antibiotics for one year. She later underwent another round of IVF and froze some embryos for possible later use. The woman eventually became pregnant with one of the embryos she had saved.

At 34 weeks of pregnancy, the woman gave birth to a baby girl who weighed 4 lbs. (1.8 kilograms). The baby is currently gaining weight and doing well, the report said.

The report is published in the Sept. 15 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds