Monkeys with brain implants are able to type out sections of the Shakespeare play "Hamlet," new research shows.

What's more, the macaques are able to type at a relatively fast 12 words per minute, with fewer typos than past brain-computer interfaces. The new brain implants could one day improve communication for those who are almost completely paralyzed, such as the polymath Stephen Hawking.

"Our results demonstrate that this interface may have great promise for use in people," study co-author Paul Nuyujukian, a bioengineer who will join Stanford faculty as an assistant professor in 2017, said in a statement. "It enables a typing rate sufficient for a meaningful conversation." [Video: Brain Implant Helps Man Drive Wheelchair With Mind]

Monkey brains

Past research has shown that monkeys can control prosthetic arms, drive robotic wheelchairs, control each others' minds and even slowly type words using their minds. However, past communication systems were typically too slow for the natural pace of conversation.

Systems currently available for people are similarly limited. Stephen Hawking, who is a quadriplegic, uses a technology that uses the minute movements of facial muscles to transcribe his thoughts, while other software relies on eye-tracking for those who are paralyzed to relay their words. However, eye- and facial-muscle tracking can take time, be tiring, and may simply be out of reach for those whose paralysis is too severe, according to the researchers.

To get around this problem, Nuyujukian and his colleagues implanted multiple electrodes inside the brains of two rhesus macaques. The team then taught the monkeys to type each letter when given a specific prompt. (The old saw is that given a typewriter and an infinite amount of time and paper, a bunch of monkeys could type the entire works of William Shakespeare by random chance, but Nuyujukian and his colleages were hoping for a more targeted effect.)

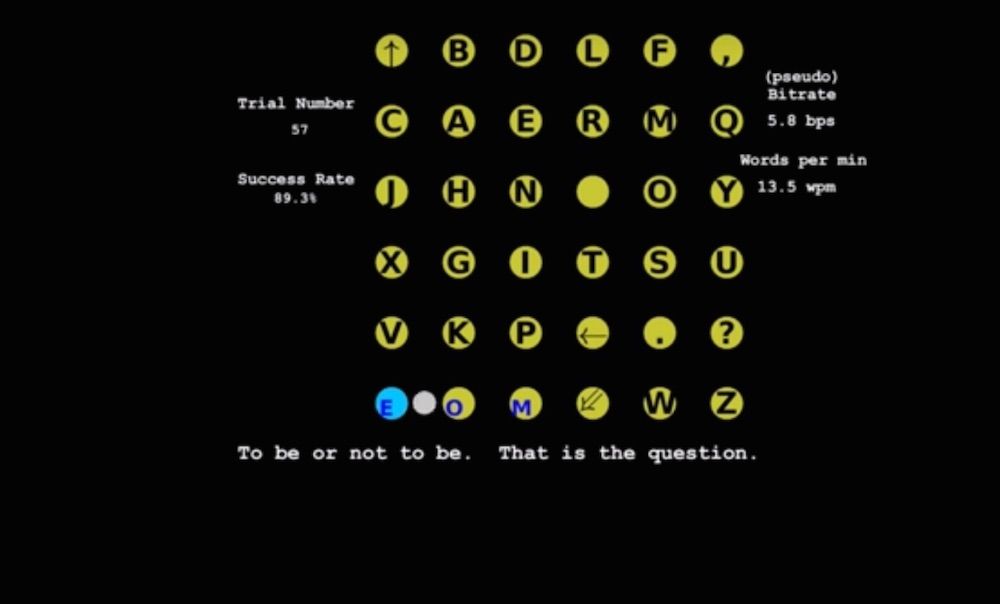

The team then prompted the monkeys one letter at a time to type the famous "To Be or Not to Be" speech from "Hamlet," as well as snippets of newspaper articles from the New York Times. The monkeys were able to type at about 12 words per minute — certainly not as speedy as the best typists but fast enough to sustain conversation, the researchers reported Sept. 12 in the journal Proceedings of the IEEE.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Talking quickly

Of course, people will be not just transcribing words but presumably thinking of them, and may also be trying to talk in busy environments, which could increase the time it takes for the system to work.

"What we cannot quantify is the cognitive load of figuring out what words you are trying to say," Nuyujukian said.

Though the relatively slow typing speed means people who use the system would likely be conversing more slowly, there are ways to offset the speed limitation, the researchers said.

"We’re not using auto completion here like your smartphone does where it guesses your words for you," which could speed up the system, Nuyujukian said.

What's more, these brain implants can remain in place safely for at least four years — the macaques experienced no side effects and showed no brain abnormalities over that length of time, the study found.

The newest version of this brain-computer interface is currently being tested in humans in clinical trials, the researchers said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.