Marsquakes Could Potentially Support Red Planet Life

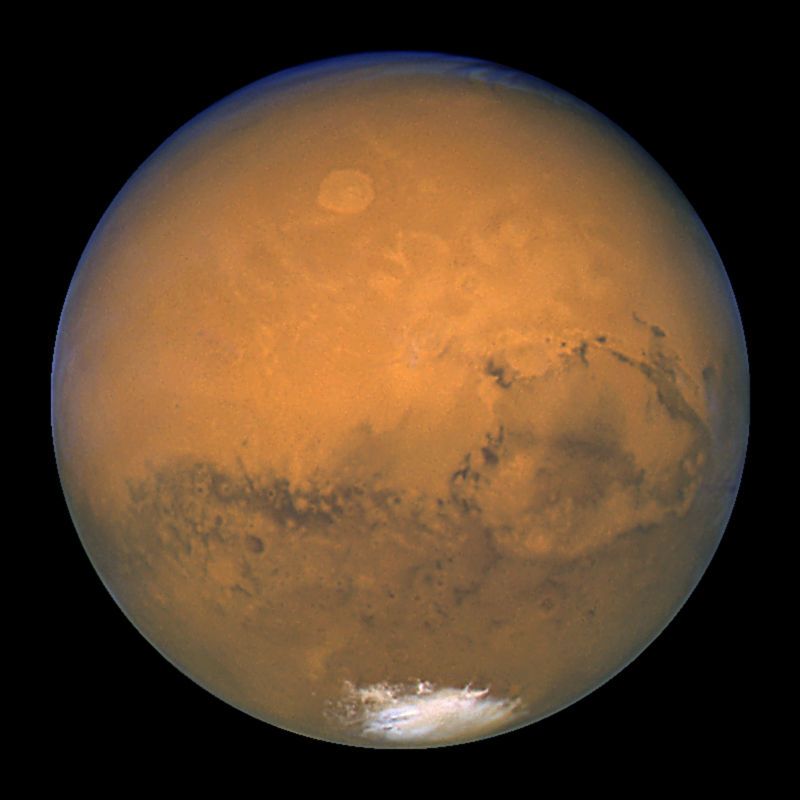

Marsquakes — that is, earthquakes on Mars — could generate enough hydrogen to support life there, a new study finds.

Humans and most animals, plants and fungi get their energy mainly from chemical reactions between oxygen and organic compounds such as sugars. However, microbes depend on a wide array of different reactions for energy; for instance, reactions between oxygen and hydrogen gas help bacteria called hydrogenotrophs survive deep underground on Earth, and previous research suggested that such reactions may have even powered the earliest life on Earth.

Prior work suggested that when rocks fracture and grind together during earthquakes on Earth, silicon in those rocks can react with water to generate hydrogen gas. Study lead author Sean McMahon, a geomicrobiologist at Yale University, and his colleagues wanted to see if marsquakes could generate enough hydrogen to support any microbes that might potentially live on the Red Planet. [The Search for Life on Mars in Pictures]

The scientists examined special types of rocks that are created when rocks grind against each other during earthquakes. The samples the researchers analyzed from Scotland, Canada, South Africa, the Isles of Scilly off the coast of England and the Outer Hebrides of Scotland were up to hundreds of times richer in trapped hydrogen gas than surrounding rocks that were not generated from such grinding.

"These findings were surprising and exciting because we didn't know if we were going to find anything at all," McMahon said.

The researchers said the hydrogen gas in the samples they analyzed was abundant enough to support hydrogenotrophs on Earth.

"Our findings are a contribution to a broader picture of how geological processes can support microbial life in extreme environments," McMahon told Space.com. "There's not much of what we think of as food miles below Earth's surface, but over the last few decades, scientists have found that Earth has a huge amount of biomass down there, maybe 20 percent or more of Earth's biomass."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

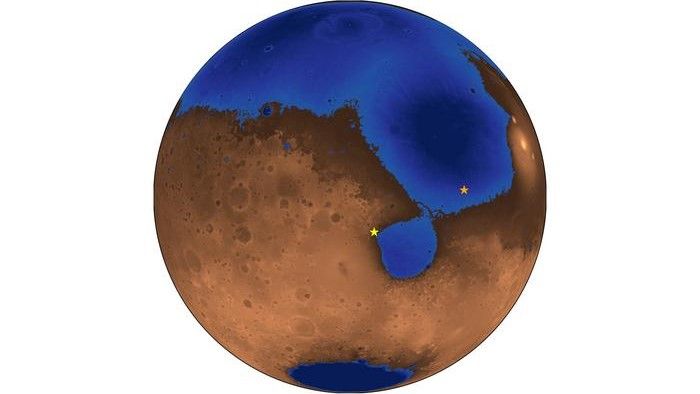

When it comes to whether marsquakes and water might work together to generate hydrogen on Mars, previous research suggested that liquid water was once abundant on the surface of Mars. It also suggests that large reserves of liquid water may still exist underground on the Red Planet at depths of about 3 miles (5 kilometers) on average. However, Mars has much fewer quakes than Earth, because the Red Planet nowadays lacks both volcanism and plate tectonics.

Still, the researchers noted that conservative models of marsquakes based off data from NASA's Mars Global Surveyor suggest that, on average, the Red Planet experiences a magnitude-2 event every 34 days and a magnitude-7 event every 4,500 years. This means that marsquakes may on average generate less than 11 tons (10 metric tons) of hydrogen annually over the whole of Mars, which may be still enough to sporadically fuel pockets of microbial activity there, the researchers said. [The Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"This hydrogen can probably support only small amounts of biomass," McMahon said. "Still, this fits into the growing picture of the kind of biosphere that Mars might be capable of sustaining. If you look at bacteria and other microorganisms on Earth, you find ones capable of resting in a dormant state for extremely long periods of time, and they can wake up and reproduce and then go back to sleep again for another 10,000 years or so."

McMahon noted that even rocks that lack water can apparently generate hydrogen gas during earthquakes. This suggests that grinding might release hydrogen that is ordinarily chemically bound to rocks. "A lot of work needs to be done to understand how hydrogen can be liberated," he said.

NASA's 2018 InSight mission is scheduled to measure seismic activity on Mars. "Having actual data of marsquakes from the surface of Mars will show whether what we've done here is really relevant or not," McMahon said.

McMahon and his colleagues John Parnell at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland and Nigel Blamey of Brock University in Canada detailed their findings in the September issue of the journal Astrobiology.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.