Naval Whodunit: How the Doomed Crew of Arctic Expedition Died

The crew on the doomed 1845 Franklin Expedition aimed at navigating the fabled Northwest Passage likely didn't die of scurvy, but rather from tuberculosis, respiratory illness and cardiovascular disease, a new study finds.

The crew also likely suffered from physical injuries while hunting wild game and making their way through terrain in the Canadian Arctic.

The findings, however, aren't based on a direct examination of the naval expedition's logs — those have never been found. Rather, the researchers said, the discovery is based on the so-called "sick books" of the ships that were sent to search for the expedition's survivors: the HMS Assistance, Enterprise, Intrepid, Investigator, Pioneer and Resolute. [In Photos: HMS Erebus Shipwreck Solves 170-Year-Old Mystery]

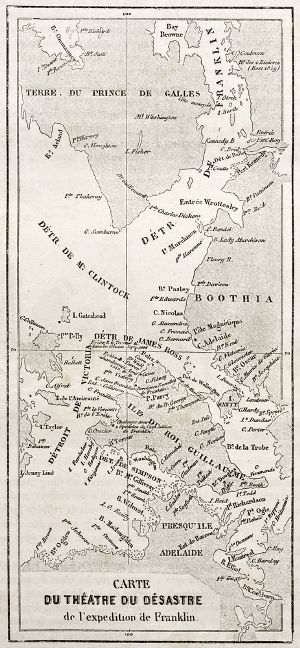

The Franklin expedition has long fascinated historians. Rear Adm. Sir John Franklin led the Royal Navy's 1845 to 1848 expedition to navigate the Northwest Passage, a sea route connecting the northern Atlantic to the northern Pacific Ocean. In 1846, the expedition's two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, became trapped in ice near King William Island in the Arctic. Some of the men initially survived, with research suggesting they relied partly on cannibalism to make it. Even so, eventually all 129 of them died, including Franklin, who passed away in 1846, archaeologists told Live Science in 2015.

The expedition's failure sparked one of the largest naval search parties in history. In 1850, three ice-preserved corpses were found in the northern Arctic, and the rest of the crew's remains were discovered much farther south in 1859. Rescuers also found a single-page document detailing how ice had trapped the ships, and that the crew had deserted them in 1848, the researchers said.

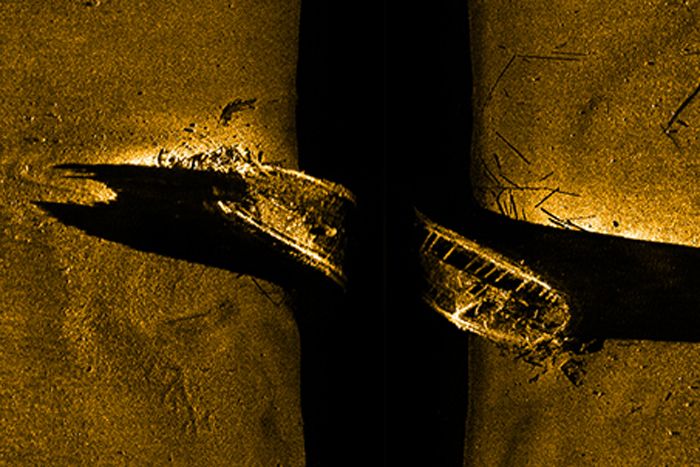

In 2014, Canadian researchers used sonar images to uncover the HMS Erebus and its bell. More recently, this month, scientists reported they had potentially found the resting spot of the HMS Terror.

However, experts have yet to uncover the sick books kept on the two expedition ships. This hasn't stopped scientists from speculating about what killed the 129 crew members, with some suggesting tuberculosis, scurvy and lead poisoning as top culprits.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To better understand the issue, a team of researchers from the University of Glasgow in Scotland looked at 1,480 "sick book" illness and death records found on the ships that were sent to find the expedition.

The types of illnesses seen in the search crews were likely similar to those experienced by the crew in the Franklin Expedition, the researchers said. For instance, an analysis showed that the crew likely lived with common respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders, injuries, and exposure to the cold, the researchers said.

There wasn't much evidence, however, of either scurvy (a disease linked to a lack of vitamin C) or lead poisoning, the researchers noted.

"Scurvy occurred commonly [at sea], despite the provision of lemon juice to prevent the disease," Keith Millar, a professor in the College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences at the University of Glasgow, said in a statement. "However, based on the evidence from the search ships, and analysis of the skeletal remains of some Franklin crewmen by other researchers, it seems that scurvy may not have been significant at the time when Franklin's crews deserted the ships."

Likewise, lead poisoning was unlikely, even though the solder that sealed the canned provisions aboard the expedition contained lead, Millar said. That's because the rescuers in the search party also had these lead-containing cans, but those men didn't die from lead poisoning, Millar said.

"Unless a unique source of lead was present on Franklin's ships, there is no clear evidence that lead poisoning played a part in the disaster," Millar said. A previous study published by Millar and his colleagues that analyzed lead in the crews' remains came to the same conclusions.

Millar added that tuberculosis was often a top killer aboard naval vessels, but there was little evidence that it caused significant losses among the search parties. Instead, just like those participating in the search parties, the crewmembers from the Franklin expedition probably experienced accidents and injuries sustained from hunting wild game or from trudging through the harsh climate and terrain, the researchers said.

Questions about the crew's last years may be answered if future excavations uncover the expedition's sick books, Millar added.

"We understand from our colleagues in Parks Canada that if any of the expedition's written records were stored securely on board, then the underwater conditions are such that they may remain in a legible condition," he said. "If a 'sick book' has survived on one of these ships, it may record the events that led to the failure of the expedition and put an end to further speculation, including our own."

The study was published in April in the journal Polar Record.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.