Scopes Monkey Trial: Science on the Stand

The Scopes "Monkey" Trial was an American legal trial in Dayton, Tennessee, during the summer of 1925. Also known as The State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes, the case tried high school substitute science teacher John Scopes for violating Tennessee's ban on the teaching of evolution in all public and state-funded Tennessee schools. The ban, formally the Butler Act, was passed in March of 1925, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The trial lasted eight days. John Scopes was found guilty but the verdict was overturned on a technicality. The true importance of the trial was not the verdict, however; the Scopes trial increased American awareness and interest in the issue of teaching theology and/or modern science in public schools. It also drew attention to the divide between religious Fundamentalists and Modernists who took a less literal approach to the Bible and supported modern science, as well to the schism between urban and rural American values.

According to the Philadelphia Independence Hall's US History website, despite the ruling, the public saw Scopes and supporters of evolutionary theory as the victors in the case. Though the debate over teaching evolution in American public schools continues today, the Scopes trial proved to be highly influential in American culture. "It is, for better or for worse, emblematic of the creationism/evolution controversy," said Glenn Branch, an author, philosopher and deputy director of the National Center for Science Education. "It showcased the enduring themes of creationist rhetoric and provided a template through which many continue to understand the controversy."

The Scopes trial inspired the 1960 film "Inherit the Wind." The film is not a documentary and contains several exaggerations and historical inaccuracies.

Historical background

In his book "When All the Gods Trembled: Darwinism, Scopes, and American Intellectuals," historian Paul Keith Conkin argued that the Scopes trial was one of the most dramatic events that came about in the wake of the publication of Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of the Species" in 1859.

Darwin's theory of evolution sent shockwaves across the world, and while many scientists and naturalists embraced it, some people found it disturbing. In America, churchgoers and religious leaders debated whether to accept the modern scientific theory, especially as it pertained to the origins of humans, or to reject it in favor of their traditional literal reading of scripture. According to US History, many urban churches decided to reconcile evolution with their beliefs, but rural churches maintained a stricter stance.

Branch explained other significant factors that led to the Scopes trial, in addition to the increasing prominence of evolutionary theory. One such factor was World War I, which had ended just seven years before. "There were a few who blamed the war in part on the acceptance (and misunderstanding) of evolution by German militarists, including even confirmed evolutionists," he told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Additionally, after the war, American public education expanded. "For the first time, students, particularly in rural areas, were being expected to continue their education into high school, and were correspondingly being exposed to more … with books like Hunter's 'A Civic Biology' — which broached the conception of evolution — being used throughout the country (including Dayton, Tennessee)."

Branch also noted the importance of the early 20th century revival of Fundamentalism. Evolution was not initially a target of Fundamentalism, but became one by the 1920s.

Controversy comes to Tennessee

According to Conkin, John Washington Butler was a member of the Tennessee House of Representatives, a farmer, and a Baptist. Butler decided that Tennessee textbooks contradicted the Bible. He drafted a bill prohibiting teaching "Evolutionary Theory" in any state-supported schools, colleges, or universities. It banned teaching any theory that suggested man descended from "lower animals" or that contradicted divine creation. Though the bill was vague and "Evolutionary Theory" had a wide definition in Tennessee at that time, it was passed and became the Butler Act in March 1925.

On May 4, a newspaper published an announcement: the ACLU was looking for a teacher willing to rebel against the Butler Act. The ACLU would defend the teacher in court for free. The next day, local business leaders decided that holding the trial in Dayton would put their town on the map (and hopefully bring jobs; the town had been struggling economically). They asked 24-year-old substitute science teacher John Scopes to participate, and he agreed.

"Scopes was willing to be the defendant in part because he accepted evolution and objected to the law, and probably in part because he had witnessed the faculty at the University of Kentucky successfully lobby against a similar bill," said Branch. Scopes had studied law in college and was working in Dayton to save money for law school. Therefore, said Branch, he was not concerned about negative career consequences from the trial.

Scopes was voluntarily arrested by his good friend Sue Hicks, Dayton city attorney, and, said Branch, inspiration for Johnny Cash's hit "A Boy Named Sue." The town prepared for the trial by outfitting the courtroom with the latest broadcast technology, constructing a pedestrian mall and tourist camp, hanging banners, and creating an overall carnival atmosphere.

The trial began July 10. Nearly 1,000 people crammed into the courthouse. Outside, people opposed to evolution sold anti-evolution literature and performed a side show with chimpanzees, according to Douglas O. Linder, a law professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Bryan and Darrow: A match made in legal heaven

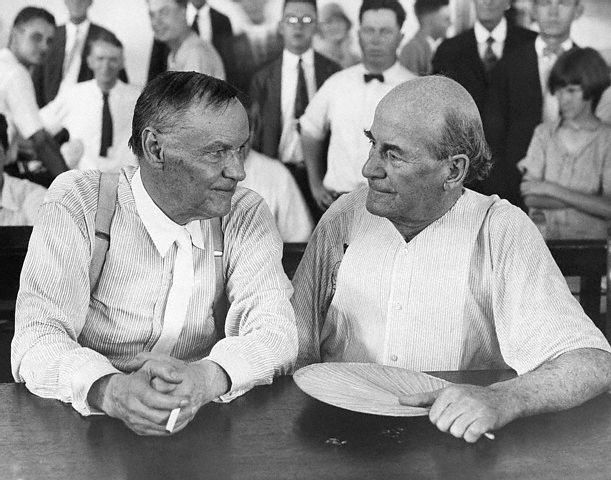

One reason the public flocked to Dayton was to witness two superstar attorneys known to have outsize personalities: William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for the defense.

Bryan was a three-time Democratic presidential nominee, former secretary of state, and charismatic anti-evolution leader popularly known as "The Commoner." Though he had not practiced law in 30 years, he volunteered for the case. H.L. Mencken, the cynical and snarky journalist from "The Baltimore Sun," portrayed Bryan as symbol of anti-intellectualism and Southern ignorance (Bryan was from Illinois). That was an oversimplification, according to US History.

In addition to contradicting his religious beliefs, Bryan believed that teaching evolution violated local control of school curricula, promoted laissez-faire capitalism, and justified war and imperialism. Furthermore, Bryan was not opposed to science. He belonged to several national science organizations. In his book "Darwinism Comes to America," historian Ronald L. Numbers notes that, in private, Bryan did not always take the Bible literally.

At nearly 70, Clarence Darrow was an old antagonist of Bryan's. When Darrow learned of Bryan's involvement in the Scopes trial, he volunteered for the defense. Darrow was famous for his agnosticism, wit, and history of defending notorious murderers, according to Conkin. The ACLU did not initially want him as a defense attorney (one of the Dayton businessmen involved in getting the case going wanted H.G. Wells) out of concern that his "zealous agnosticism might turn the trial into a broadside attack on religion," according to Linder.

Other attorneys played important roles, including Arthur Garfield Hays, a free speech advocate, and Dudley Field Malone, an international attorney, on the defense, and two former attorney generals of Tennessee and Bryan's son for the prosecution.

The trial

Fundamentalist Christian judge John Raulston presided over the trial. He opened each day with a prayer in spite of Darrow's objections. Scopes' role was small; the trial quickly became a verbal battle between lawyers. Bryan claimed it was a choice between evolution or Christianity; Darrow said that civilization itself was on trial.

Bryan originally hoped to attack the scientific status of evolution, said Branch, but was unable to find expert witnesses. Therefore, the prosecution quickly called witnesses who had seen Scopes' admitting he taught evolution and rested their case.

The ACLU had never intended to win the case, according to Numbers. Rather, they wanted to appeal it to the Supreme Court, where they believed they could test the constitutionality of the law. They believed the Butler Act violated the 14th Amendment. "Hays wrote that the goal was to make it 'possible that laws of this kind will hereafter meet the opposition of an aroused public opinion,'" said Branch.

The defense made several arguments. Hays argued that the Butler Act violated the rights of teachers, said Branch. "Malone (a liberal Catholic) emphasized that evolution isn't necessarily in conflict with Genesis but only with a particular literalistic reading of it. Darrow emphasized that scripture is not a suitable basis for legislation about what is taught in public schools."

Malone's argument was likely the most influential on public opinion. It is Branch's opinion that the most rhetorically effective speech was Malone's "Duel to the Death," given early in the proceedings and regarded by Bryan, Scopes and Mencken as the best of the trial. "Darrow's hostility toward religion probably made it harder for his argument to be well-received," added Branch.

The defense hit a roadblock when Raulston refused to let them call expert scientific witnesses to validate evolutionary theory. Darrow had an unorthodox response: since he could not defend Darwin, he decided to challenge the Fundamentalist reading of the Bible.

On the seventh day of the trial, which had been moved outside, the defense began what "The New York Times" called "the most amazing court scene in Anglo-Saxon history." Bryan himself was called to testify as an expert on the Bible.

Things began calmly, writes Linder. "You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven't you, Mr. Bryan?" asked Darrow. Bryan politely replied that he had studied it for about 50 years. Bryan's expertise thus established, Darrow began a series of questions that undermined Bryan and the literal interpretation of the Bible at every turn. Darrow asked Bryan about believing that a big fish had really swallowed Jonah, that Joshua had made the sun stand still, the truth of Adam's temptation and of the Genesis creation story.

As he was questioned, Bryan became flustered. According to US History, perhaps the most famous exchange involved the story of Noah's Ark. When asked about the process of determining when the flood occurred, he said, frustrated, "I do not think about things I don't think about." Darrow replied, "Do you think about things you do think about?" Bryan replied, "Well, sometimes," to derisive laughter.

Exasperated, Bryan said that Darrow was slurring at the Bible. Darrow said that Bryan had "fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on earth believes." At that, Raulston halted the trial and adjourned the court. The next day he ruled that Bryan's testimony should be stricken from evidence.

The damage to Bryan and the Fundamentalist side had already been done, however; the press proclaimed Darrow the victor of the examination. Darrow was out of options for the case, and hoping to ensure an appeal to the Supreme Court, asked the jury to find Scopes guilty. This move prohibited Bryan from giving his closing remarks, said Branch, and historians wonder if the public perception of the trial would have been different if he had been able to speak. Scopes was found guilty and fined $100.

Six days after the trial, Bryan lay down for a nap after a big dinner and died in his sleep.

A year later, the verdict was overturned on a technicality so the ACLU could not appeal the ruling.

Influence

The Scopes trial has had a wide-reaching effect on American culture and policy regarding the evolution education debate.

Bryan made three claims that continue to be influential, said Branch: "Evolution is scientifically problematic; that evolution undermines morality, society, and religion; and that this position on teaching evolution is supported by secular considerations like fairness, objectivity, etc." These ideas have been called the pillars of creationism.

The public perception, heavily influenced by the media's coverage of the case, was that the anti-evolution crusade was dealt a serious blow. Linder wrote that in 1925, 15 states had anti-evolution legislation in the works, but after the trial only Arkansas and Mississippi passed the laws.

"But," said Branch, "the case had a chilling effect on the teaching of evolution. Fearing controversy, publishers frequently removed, downplayed, or used euphemisms in the treatment of evolution in their textbooks — including Hunter's "Civic Biology." This development was not reversed till the 1960s, as the federal government started to pour money into science education as part of the Space Race with the USSR.

"We don't have a good baseline for the situation before Scopes, but a 1940 national survey of high school biology teachers found that only slightly more than half were teaching evolution (and teachers from parochial and Southern schools were probably underrepresented in the survey, so that overstates the likely rate); one in five reported avoiding or denying it. It's hard not to believe that the memory of the Scopes trial played a role."

Branch advised against interpreting the Scopes trial as the creationism/evolution controversy in a nutshell. "It was artificial, overblown, and not decisive; a lot of its features are peculiar to its historical context (constitutional law, for example, has developed significantly since the 1920s)," he said. Nevertheless, it is the form through which many understand controversy. As recently as 2012, a Tennessee legislator dubbed a new anti-evolution legislation "the monkey bill."

The memory of the Scopes trial lingers in the American consciousness because of its larger-than-life players, its rhetorical spectacle and, perhaps most of all, because it raised questions that continue to divide the country.

Additional resources

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.