Up She Goes! 8 of the Wackiest Early Flying Machines

Making history

"They go up diddley up-up, they go down diddley down-down …" So goes the classic song from the 1965 flim "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines," a comedy about a fictional 1910 aviation contest to fly from London to Paris.

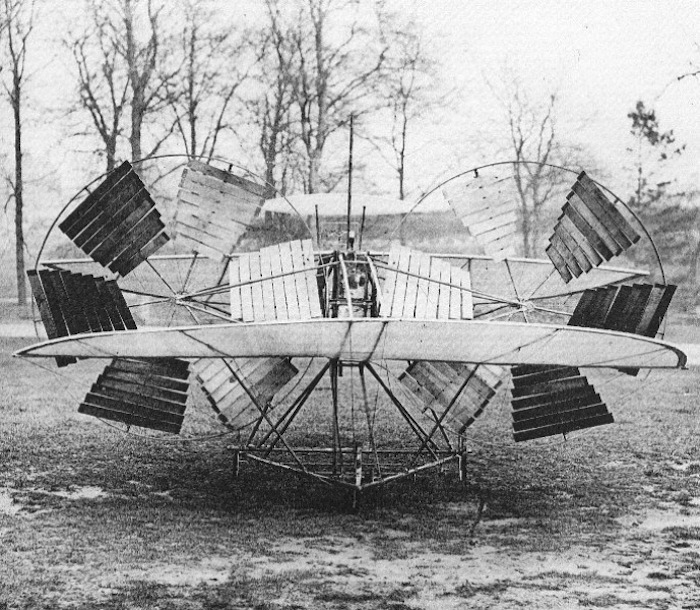

The early inventors and aviators who dreamed that people could fly made many painful mistakes, but their vision, perseverance and faith — a lot of faith, really — led in time to modern aircraft and the aerospace technologies that have opened up the skies for exploration. Here are 8 of the wackiest flying machines from the very earliest days of aviation, most of which were actually able to get off the ground, at least briefly — unlike the elegant, but flightless, French "Marquis' Multiplane" of 1908, shown above.

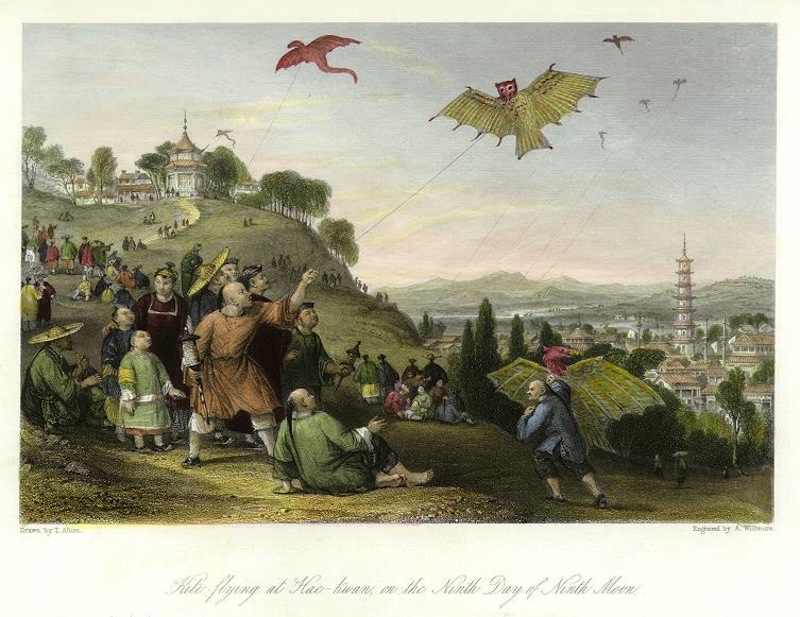

Chinese war kite, 500 B.C.

Kites large enough to carry a man were first used in China thousands of years ago, mainly for military observation and sometimes as a punishment for errant soldiers or prisoners. The Chinese general Kung Shu-Pan, a contemporary of Confucius in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C., is recorded as having "himself made an ascent riding on a wooden kite in order to spy on a city which he desired to capture." The kite was shaped like a bird, and could stay aloft for three days and three nights.

In 1282, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo described how authorities at a seaport would strap an unwilling victim onto a large rectangular kite, and send him aloft to determine the wind direction (a bit like a weather vane) and the best time for ships to set sail.

Kites continued to be used for military observation at different times and places right up to the time of the earliest balloons and airships. Powerful lifting kites were used as a fairground attraction developed by the Wild West showman and aviation pioneer Samuel Franklin Cody, including very large bat-winged box kites that could lift several people in a gondola to altitudes of several thousand feet.

Observation kites were also used by the British in the Boer War in South Africa in the 1890s. The British used several war kites designed by Cody from 1906 until they were replaced by observation balloons and aircraft during World War I.

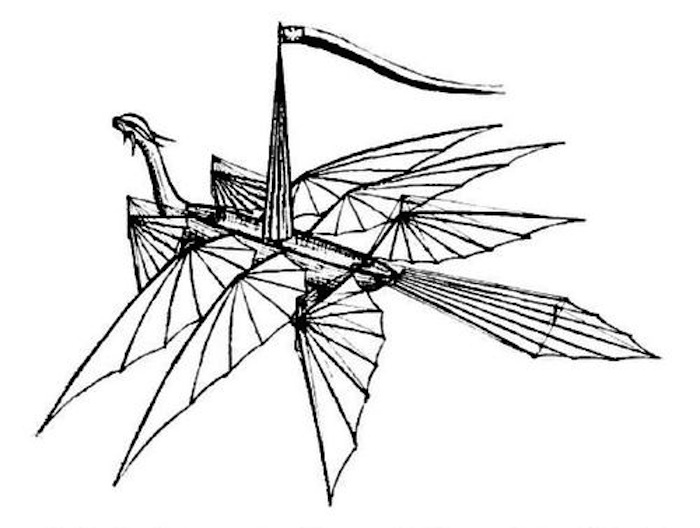

Clockwork Flying Dragon, 1647

The Italian inventor and early scientist Tito Burattini demonstrated a flying model glider that he called the "Dragon Volant" (Flying Dragon) at the court of the King of Poland in Warsaw in 1647. From contemporary descriptions and later drawings of device, such as the one shown above, it may have been made from cloth or paper stretched over a wooden frame, with four flapping wings driven by springs.

In 1648, Burattini launched the Dragon Volant once more, this time with a cat aboard, for a brief but surely turbulent gliding flight, thereby establishing a tradition followed by the animal astronauts of the American and Russian space programs in the 20th century.

It’s reported that Burattini was unable to convince the king to finance a full-sized version of the Dragon Volant, large enough to carry himself, but he was certain that "only the most minor difficulties" would be involved in landing his mechanical dragon if he could get off the ground.

Emergency parachute, 1783

Several inventors seized on the idea of a parachute long before anyone ever got one to work, including Leonardo Da Vinci in the 15th century, who drew a pyramid-shaped parachute that he described as "a tent made of linen of which the openings all stopped up … [a man] will be able to throw himself down from any great height without suffering any injury."

In 1595, the Croatian inventor Fausto Veranzio published a design for the Homo Volans, or "Flying Man," a parachute based on a ship's sail, with material stretched across a square wooden frame with ropes.

History does not record all the painful flight experiments that must have followed, but on Dec. 26, 1783, the French inventor and scientist Louis-Sébastien Lenormand made what is considered to be the first successful decent by parachute, from the tower of the Montpellier observatory, shown in this 19th-century illustration.

Lenormand thought his invention could be used in an emergency to escape from the upper floors of buildings in case of a fire, and for his public test flight, he descended safely from a height of about 82 feet (25 meters) using a parachute measuring 14 feet (4.3 m) across, with a wooden frame of spokes like an umbrella, covered with silk.

The crowd in front of the observatory for the demonstration included the balloonist Joseph Montgolfier, who had pioneered the first manned air balloon flights with his brother Etienne just a few months earlier in the same year.

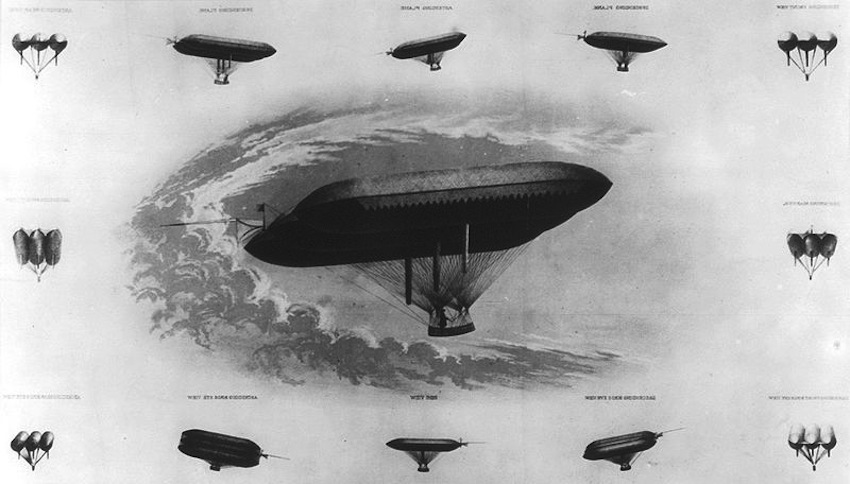

Aeron dirigible, 1863

American airship pioneer Solomon Andrews first flew his Aeron dirigible, or steerable airship, over Perth Amboy in New Jersey in 1863. The pilot then flew over New York City in 1866, making it as far east as Oyster Bay, New York. Andrews also wrote to President Abraham Lincoln, offering the use of the Aeron in the American Civil War, but the government reportedly showed little interest in the idea.

The Aeron had no engines, but used a wing-shaped compound gasbag design and steering vanes that let Andrew control his height, speed and direction by what he called "gliding under gravity" — using speed to create lift as the airship alternatively sinks and rises.

Andrews' ideas inspired later experimental airship designs and these vehicles remain promising concepts for several experimental airship designs today, such as the Airlander Hybrid Air Vehicle, which gets some of its lift from lighter-than-air gas and some from its shape and motion.

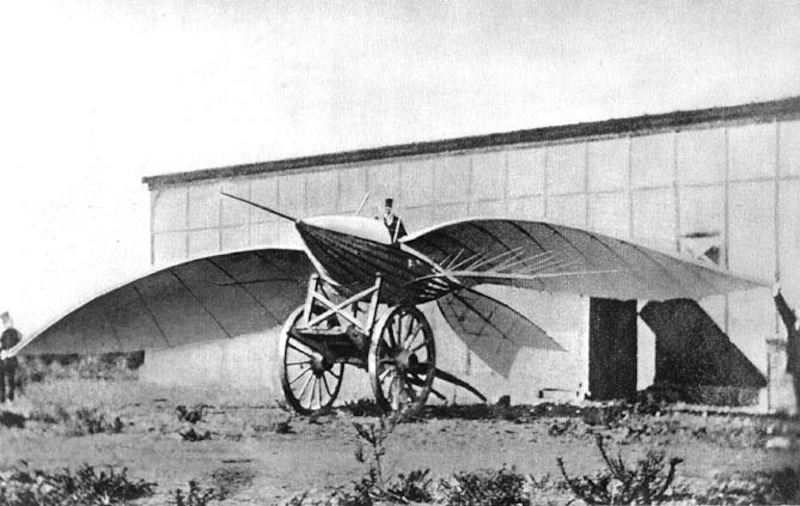

Artificial Albatross 1868

French inventor Jean-Marie Le Bris was inspired to build his graceful piloted gliders by watching the flight of the albatross during his sailing voyages around the world. He studied the anatomy of birds, and the phenomenon of lift created by their wings. Hoping to take flight himself using the same phenomenon, Le Bris built a glider, named L'Albatros Artificiel, inspired by the shape of the bird he’d seen on his travels.

In 1856, Le Bris successfully flew his "Artificial Albatross" on the windy beach of Sainte-Anne-la-Palud, near the extreme eastern point of France. The aircraft was placed on a cart towed by a horse, which gave it enough speed to reportedly reach a height of 330 feet (100 meters), flying for a distance of 660 feet (200 m), and landing at a point higher than his point of departure, a world first for a heavier-than-air aircraft.

In 1868, with the support of the French Navy, Le Bris experimented with a lighter version of his Artificial Albatross with better control, by distributing his body weight — the principle used in modern hand gliders and parasails — and wings that could tilt. This image of Le Bris and the later aircraft in the city of Brest in 1868 is thought to be the first photograph of a flying machine.

Aerial steamer, 1875

The aeronautical design principle of "if it won’t fly, add more engines" found early expression in the first attempts to build powered aircraft in the late-19th century, when steam engines first became small enough to be practical in aeronautical designs.

In 1875, Thomas Moy successfully flew the unpiloted "Aerial Steamer" tandem-wing aircraft, shown in this image, which was powered by a 3-horsepower steam engine that drives large twin propellers.

The aircraft weighed almost 210 pounds (100 kilograms) but was able to fly for very short distances under its own power, about 6 inches (15 centimeters) off the ground, tethered above a circular track built in a former ornamental fountain at Crystal Palace in London, in the United Kingdom.

Otto ornithopter, 1894

Many early flight pioneers looked to birds for inspiration, and reasoned that since birds flap their wings when they fly, then the same technique might work for human flight. Leonardo Da Vinci drew a design for a mechanical wing in the early 15th century, and many designs for what became known as ornithopters — aircraft that flap their wings — were proposed in the 18th and 19th centuries. One inventor in France in the early 1800s reportedly used an ornithopter attached to a small hydrogen balloon to make small hops.

This image from 1894 shows the German aviator Otto Lelienthal with his human-powered ornithopter.

Lelienthal had become famous in Germany after making a series of successful early glider flights, and he hoped his muscle-driven "kleiner Schlagflügelapparat" (which translates to "little flapping apparatus") would enable him to fly like a bird.

But he was killed in a crash while flying a fixed-wing glider in 1896, before he could complete the development of his ornithopter design.

Today, scientists recognize that the way birds use their wings to fly depends on a highly evolved lightweight physiology and flying senses that let them control their wing shape and surface texture, and finely adapt it to efficiently produce the lift they need at any moment.

Some scientists are now studying how the brains of birds, bats and insects can handle such complex information about flight with only small brains, and hope that such "bio-inspired" research can teach them more about efficient flight for aerial drones.

Cornu helicopter 1907

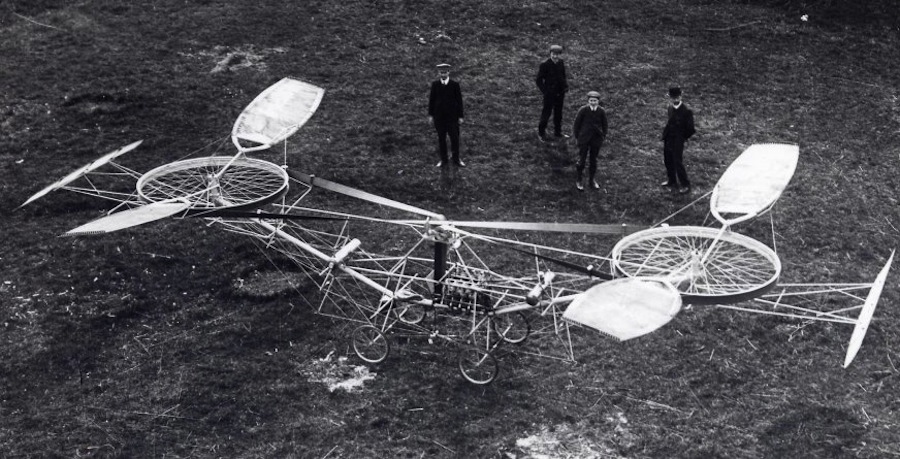

French flight pioneer and bicycle maker Paul Cornu made the first free helicopter flight in this remarkable contraption on Nov. 9 1907. The primitive helicopter has two rotors mounted one in front of the other, and the pilot sat between the rotors, with the 24-horsepower petrol engine between his knees.

Steerable control vanes were included under the rotors, but they didn't seem to work, and the pilot steered mainly by rocking the helicopter from side to side, and moving the nose up and down.

The first flights were made with the helicopter tethered to the ground, but in time Cornu was able to make several free-flying hops of up to 6 feet (2 m) in height, and only long enough to learn that the machine was almost uncontrollable.

Cornu abandoned working on his prototype helicopter soon after those first experimental flights, and eventually returned to making bicycles for a living.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.