Your Brain on Tetris: How Video Game Seduced Millions

In the 1980s, a humble yet compelling computer puzzle game called Tetris unexpectedly transformed into an addictive global phenomenon that consumed countless waking hours of obsessed players around the world.

Now widely considered to be the most popular computer game of all time, Tetris' simple design and repetitive gameplay triggered responses in the brain that attracted people of all ages and from all walks of life — and kept them coming back for more.

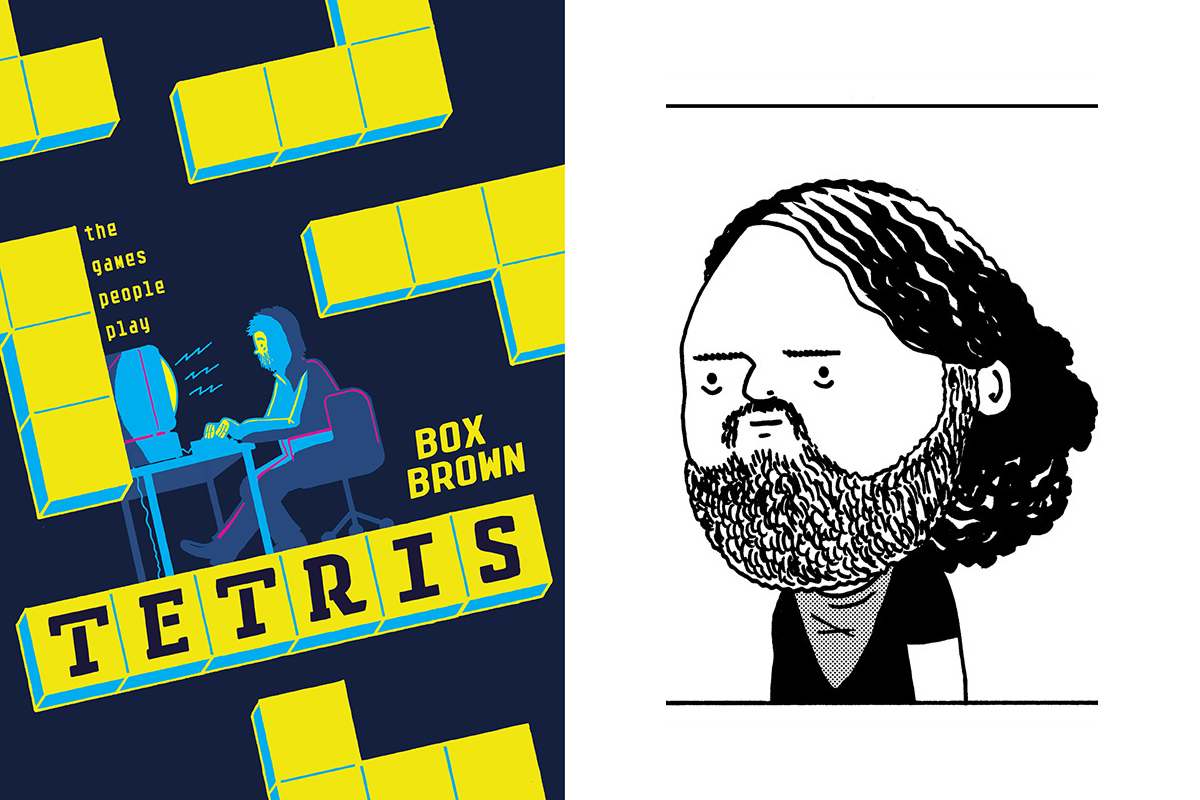

The remarkable and largely unknown story behind the game that transfixed millions — and continues to do so today — unfolds in the nonfiction graphic novel, "Tetris: The Games People Play," by Box Brown, released in the U.S. Oct. 11 by First Second Books. [Too Much of a Good Thing? 7 Addictive Educational iPad Games]

When Brown discovered a 2004 BBC documentary about Tetris, he was inspired to dig deeper into the game's backstory, which began in the former Soviet Union. Tetris' creator, a software designer named Alexey Pajitnov, developed the game in his spare time just for fun. And when he shared it with his colleagues, they all had the same reaction — they couldn't stop playing it.

Eventually, video game executives in the West heard about Tetris and jockeyed furiously for control of foreign rights to the game, which by then was in the hands of Soviet officials.

"For Alexey it was a pure art project," Brown told Live Science. "Once it entered the free market, something else happened. There was this crazy fight for the rights, and it became an international bestselling game that was on every computer, every game system that came out — everyone had their own version of it."

Suddenly, Tetris was everywhere. And like many people who grew up during the 1980s, Brown played Tetris extensively as a child. Even as a 9-year-old, he noticed there was something unusual about it.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It wasone of the only games I had that my parents would also play with me," he said. "That was a huge deal."

Unlike many games at the time that were marketed specifically for children, Tetris didn't have characters or a story that could alienate older players, which could explain its age-spanning appeal, Brown said.

Your brain on Tetris

During Brown's research for the book, he consulted with a neuroscientist to understand what happens in the brain when people play Tetris, and what compels them to keep playing once they start. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Brown explained that the appearance of each Tetris tile in the frame signals your brain that there's a new problem to be solved. Guiding that piece into position creates closure and brings satisfaction. Those two steps — culminating in a satisfied feeling — repeat as long as you play the game, and provide motivation to continue playing.

"Every time you put a new piece down you're getting a new resolution," Brown said. "So it's constantly feeding this sense of completion."

And scientists have found that playing Tetris can provide benefits other than a feeling of satisfaction for a game well played.

Research presented in 2012 at the British Psychology Society Annual Conference suggested that playing Tetris could lessen symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and protect against traumatic flashbacks. And a study published in the journal Addictive Behaviors in 2015 found that playing Tetris weakened cravings for drugs, activities and food.

Study co-author Jackie Andrade, a psychology professor from the School of Psychology and the Cognition Institute at Plymouth University, said in a statement that Tetris was likely so effective because when we crave something, we imagine ourselves consuming the desired substance or taking part in the longed-for activity — and playing Tetris blocks that visualization.

"Playing a visually interesting game like Tetris occupies the mental processes that support that imagery," Andrade said. "It is hard to imagine something vividly and play Tetris at the same time."

One more level

Decades have passed since the first Tetris pieces quickened heartbeats as they dropped smoothly into place, but for many players the game is still going strong. In fact, a number of variations on the original version are currently available as apps, and on websites, game systems and social media platforms.

Even Brown still finds himself revisiting the game from time to time.

"I still play Tetris," Brown said. "I have the original Nintendo version of Tetris, I have these old game-in-watch versions of Tetris. You can put it down, pick it up, and it's still good. It's like riding a bike — it's always fun to do."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.