7 Weird Facts About Tetris

One more row

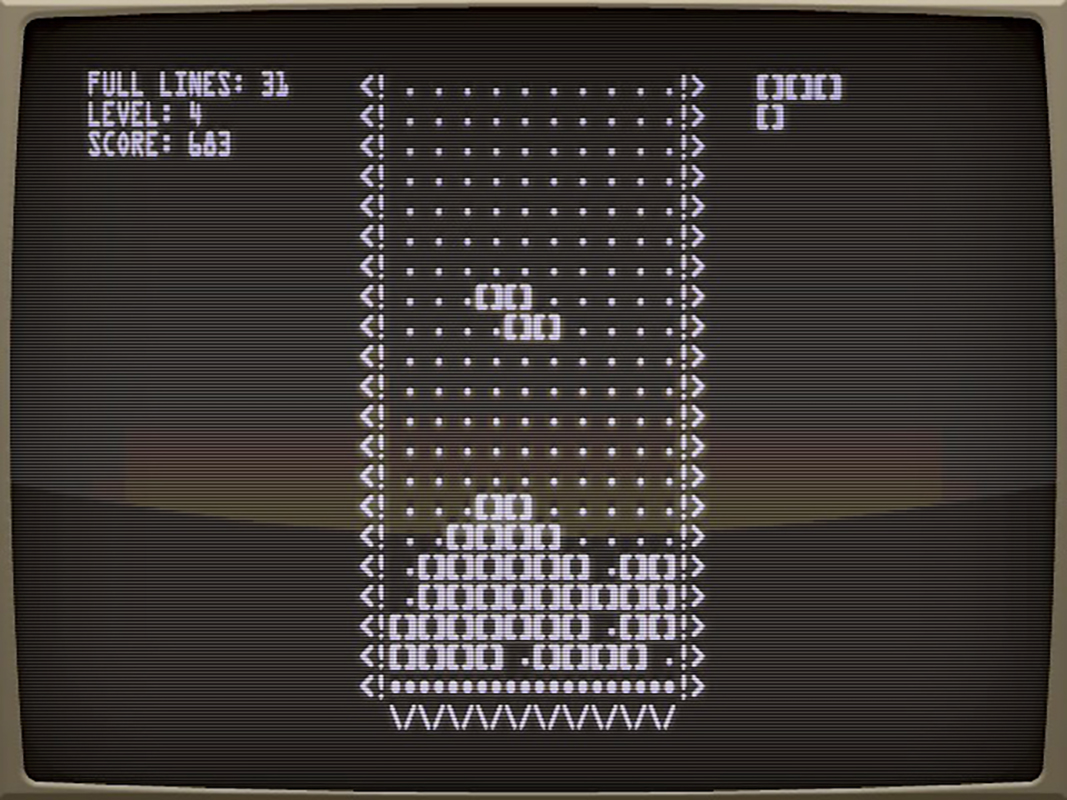

It was the game you played so obsessively that perhaps you remember seeing the falling shapes in your sleep.

What began as a programming challenge and source of amusement for a Soviet software designer in the 1980s, eventually spread quickly from country to country. Even today, decades later, players are still drawn to Tetris, mesmerized by the simplicity of the game and how satisfying it is to play.

If you've played it — and who hasn't? — you may think that after spending hours rotating and dropping puzzle pieces to the hypnotic sound of the 8-bit theme song, that you are intimately familiar with Tetris. But the video game that hypnotized millions of people of all ages has a long and colorful history — and its narrative holds plenty of unlikely surprises. Here are seven strange facts about Tetris.

Its name was inspired by tennis (partly)

The unusual name "Tetris" was coined by its inventor, computer software designer and puzzle enthusiast Alexey Pajitnov, when he created the game in 1984. He got the idea for the shapes of the playing pieces from a popular puzzle game called "pentonimos," in which each piece was made up of five equal squares. But in Pajitnov's computer game, the pieces were made of four squares. He combined the Latin word for the numerical prefix "four" — "tetra" — with the word "tennis," since that was his favorite game.

Vadim Gerasimov, a programmer and graphic designer who worked with Pajitnov on early versions of Tetris, recalled that he was dubious when Pajitnov proposed it.

"I thought it sounded a bit strange in Russian," Gerasimov wrote on his website, "But Pajitnov insisted on giving the game this name."

It caused actual hallucinations

In the nonfiction graphic novel "Tetris: The Games People Play," author and cartoonist Box Brown wrote that people spent so much time in front of screens playing Tetris that they developed a peculiar side effect — even after they had stopped playing the game, they could still see images of falling pieces when they closed their eyes. Some people even saw Tetris tiles in their dreams

This became known as the "Tetris Effect," and in recent years has come to apply to other games that people play for extended periods of time. Also called gaming-induced pseudo-hallucinations, or game transfer phenomena (GTP), the phenomenon was analyzed in a 2014 study published in the International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction.

Some game art included a political protest

On May 28, 1987, a 19-year-old German pilot named Mathias Rust flew a single engine Cessna airplane 500 miles (805 kilometers) from Finland, illegally crossing the Soviet border and landing mid-day in Red Square.

What does this have to do with Tetris, you may ask?

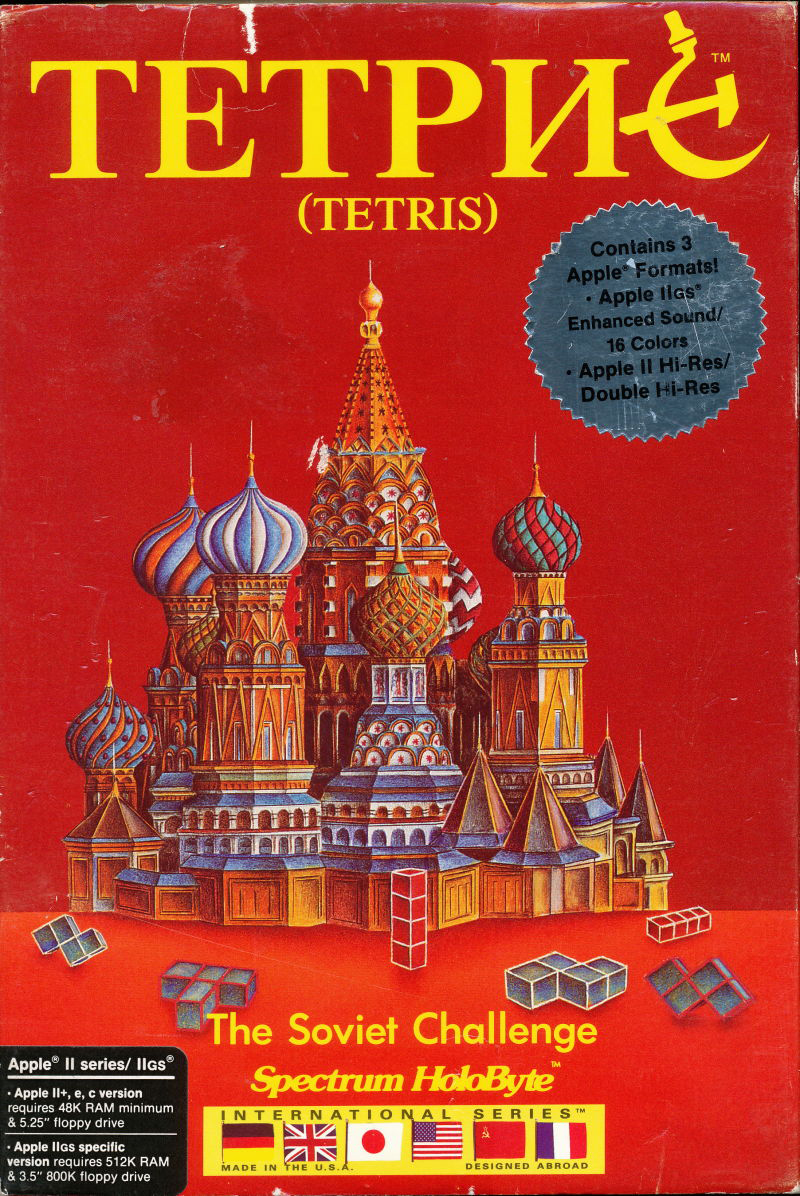

According to Brown, the distribution companies for Tetris in America and the U.K. decided to include images of Rust's plane in graphics of Russian scenes that they added to the game for visual interest. Needless to say, Rust's stunt was no laughing matter in the Soviet Union, where he was tried and convicted of "malicious hooliganism, violating international flight rules and illegally crossing the border," the New York Times reported in Dec. 1987.

The music was actually a love song

The catchy tune that plays cheerfully as gamers spin and drop their Tetris tiles was based on a folk song from the 19th century called "Korobeiniki," about the courtship between a peasant girl and a peddler.

How did it become the theme song for a game that had no romance, no characters — no story of any kind?

In the 1980s, the USSR was a mysterious place to many in the West; its culture wasn't widely exported, and there was little opportunity for people from other countries to experience its music, art, and architecture.

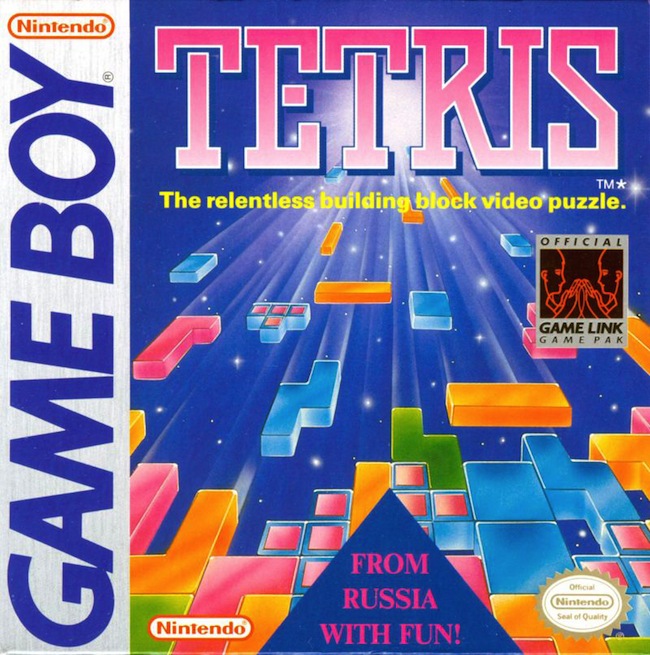

Tetris, which was created in Moscow, was a video game ambassador from this enigmatic location. When Tetris was licensed and packaged for computers, game consoles and coin-operated machines in the West, designers added "Russian" touches: images of Red Square and Soviet cosmonauts, and a theme song inspired by a traditional Russian folk ballad.

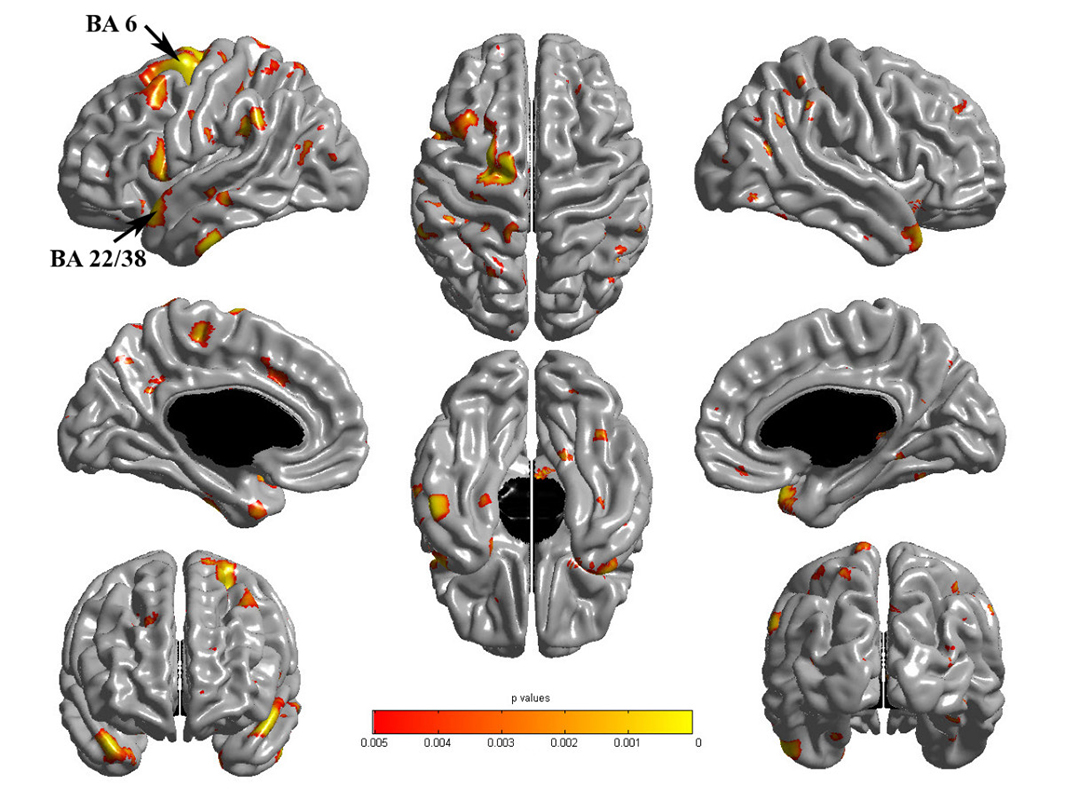

It can change the shape of your brain

Playing Tetris thickens the brain's cortex and can contribute to greater cognitive efficiency, according to a study published in Sept. 2009 in the journal BMC Research Notes.

A group of 26 teenage girls were tasked with playing Tetris for 30 minutes each day over three months. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) of their brains taken before and after the three-month period showed thickening in three brain regions — one in the left frontal lobe and two in the left temporal lobe — while there were no changes in the brains of girls who did not play Tetris.

It's a work of art

In Nov. 2012, Tetris was one of 14 video games acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, part of an initiative to develop a new category of artworks within the museum collection, MoMA officials said in a statement.

Other games in the group included Pac-Man, Myst, the Sims and Portal, and all were presented to the public as part of MoMA's "Applied Design" exhibit (Mar. 2, 2013 – Jan. 20, 2014).

The museum describes Tetris as an "abstract puzzle" that is "highly addictive" and "one of the most universal of all video games, appealing to players across lines of age, gender, and geography and adapted for nearly every gaming and computer system."

It was the first video game in space

In 1993, Tetris boldly went where no video game had gone before, when Russian cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov brought his Nintendo Game Boy and Tetris cartridge aboard the Soyuz TM-17 rocket on a Russian mission to the space station Mir.

That space-flown Game Boy and cartridge were sold at auction on May 5, 2011, one of the lots in a "Space History Sale"through Bonham's Auction House.

According to the Bonham's description, "This Game Boy spent 196 days in space and has orbited the Earth more than 3,000 times." A handwritten note from Serebrov included in the auction lot states — in Russian — "Like all cosmonauts, I love sport. My particular favorites are football and swimming. During flight, in rare minutes of leisure, I enjoyed playing Game Boy."

It sold for $1,220 USD.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.