The Bizarre History of 'Tetris'

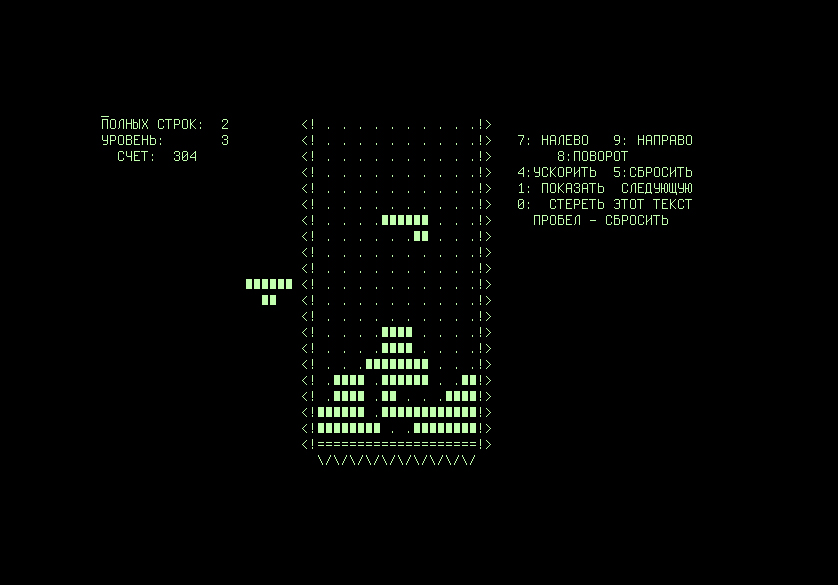

Its graphics are simple, and its rules are straightforward: rotate fast-dropping puzzle pieces on your computer screen to fit together and create solid lines — which then disappear. Repeat ad infinitum.

"Tetris," the hugely popular and addictive game that swept the world in the 1980s and 1990s, continues to engage and captivate players today. Unlike the majority of products developed during the early boom years of video game design, "Tetris" was a no-frills outlier: no fancy images, no memorable characters and no narrative.

But while the game may be uncomplicated, the story of how it came to dominate the gaming industry and bewitch millions of people around the world is quite the opposite. The tale is rife with handshake deals, game industry rivalries, and tense negotiations between Western executives and Soviet officials during the last decade of the Cold War, when relations between the USSR and countries in the West were anything but friendly. [7 Weird Facts About Tetris]

In a new nonfiction graphic novel titled "Tetris: The Games People Play" (First Second, Oct. 2016), writer and illustrator Box Brown fits together the puzzle pieces that describe the explosive gaming-world takeover of "Tetris," uncovering the unique historical circumstances in world politics and the nascent gaming industry that made the "Tetris" story so unique.

"Tetris" — "tetra" plus "tennis"

It all began with a puzzle-loving software engineer named Alexey Pajitnov, who created "Tetris" in 1984 while working for the Dorodnitsyn Computing Centre of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, a research and development center in Moscow created by the government.

Pajitnov didn't intend to make money from his creation; he designed the game "for fun," Brown told Live Science.

"He was doing this just to see if he could do it," Brown said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pajitnov was inspired by a puzzle game called "pentominoes," in which different wooden shapes made of five equal squares are assembled in a box. Brown wrote that Pajitnov imagined the shapes falling from above into a glass, with players controlling the shapes and guiding them into place. Pajitnov adapted the shapes to four squares each and programmed the game in his spare time, dubbing it "Tetris." The name combined the Latin word "tetra" — the numerical prefix "four," for the four squares of each puzzle piece — and "tennis," Pajitnov's favorite game.

And when he shared the game with his co-workers, they started playing it — and kept playing it and playing it. These early players copied and shared "Tetris" on floppy disks, and the game quickly spread across Moscow, Brown wrote. When Pajitnov sent a copy to a colleague in Hungary, it ended up on display in a software exhibit at the Hungarian Institute of Technology, where it came to the attention of Robert Stein, owner of Andromeda Software Ltd., who was visiting the exhibit from the United Kingdom. [The Top 5 Benefits of Play]

"Tetris" intrigued Stein. He tracked down Pajitnov in Moscow, but ultimately the game's fate lay in the hands of a new Soviet agency, Elektronorgtechnica (Elorg), created to oversee foreign distribution of Soviet-made software. Elorg licensed the game to Stein, who then licensed it to distributors in the U.S. and the U.K. — Spectrum HoloByte and Mirrorsoft Ltd — The New York Times reported in 1988. According to the Times, "Tetris" was the first software created in the Soviet Union to be sold in America.

Gaming the system

Stein's agreement with Elorg covered "Tetris" licensing only for personal computers, not coin-operated machines or handheld devices. But Stein told U.K. distributor Mirrorsoft that these rights would soon be in hand, and Mirrorsoft proceeded to ink licensing deals with game companies Atari and Sega in Japan for arcade kiosks and home-gaming consoles.

BulletProof Software's Henk Rogers also had his eye on brokering "Tetris" deals in Japan, and secured rights for "Tetris" distribution on computers and consoles for Nintendo, through the U.S. distributor, Spectrum HoloByte.

However, the legal owner of "Tetris," the Soviet agency Elorg, knew nothing of these deals, Brown wrote. The only contract the agency had signed was the deal with Stein covering computer rights, and nothing else.

The penny dropped when Rogers met with Elorg officials in Moscow about licensing "Tetris" for handheld devices — Nintendo had just created the Game Boy — and showed them a "Tetris" cartridge for the Nintendo Entertainment system (NES). The Soviets were outraged, but Rogers convinced them that if those rights were, in fact, up for grabs, licensing them to Nintendo — for both handheld and console devices — would be highly profitable.

Elorg agreed that Rogers could secure the handheld rights for Nintendo, with console and coin-operated kiosk rights added later, amid angry protests from Atari over the threat to their own versions of "Tetris." A prolonged legal battle between the two rival game companies followed, but was eventually resolved in favor of Nintendo; that company quickly solidified "Tetris'" hold on eager consumers across America by including a copy with every Game Boy that Nintendo sold.

For the love of puzzles

A lot of money changed hands during these deals, but Pajitnov, the game's creator, was not part of the negotiations and saw no profits at all, missing out on approximately $40 million, SFGate reported in 1998.

However, Pajitnov and Rogers had become friends, and with Rogers' help, Pajitnov emigrated to America in 1991 and devoted himself to creating games, first for his own game-design company and later for Microsoft. And in 1996, when Elorg was dissolving, Rogers went back to Moscow for a final round of "Tetris" negotiations — to return ownership of the game to the man who invented it.

In Brown's book, the unusual story of "Tetris" is interwoven with an exploration of gaming: why people do it, how it changes them and how it brings people together. Pajitnov himself began this journey simply because he loved games and puzzles and wanted to share them with the world. And in the process, Brown told Live Science, "Tetris" took on a life of its own.

"To me, this is the universal thing that happens with all art and artists," Brown said. "You make something for people, and it becomes popular. Once it goes out into the world, it can be redefined by other people and become something else entirely. This is what happened to 'Tetris.' In an extreme way, I think of it as a lens to view that theme in all art and commerce."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.