T. Rex Probably Didn't Use Its Tiny Arms Much

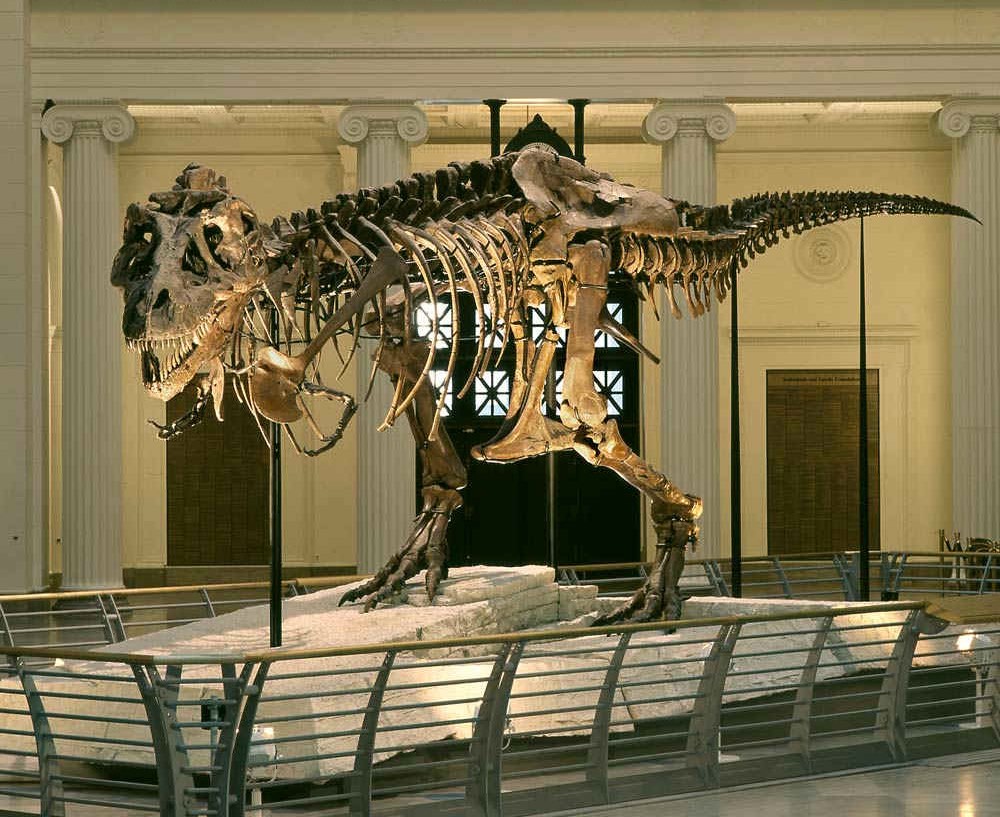

Sue the Tyrannosaurus rex — the most complete and best-preserved T. rex skeleton ever found — temporarily surrendered her arm to science. And the preliminary results suggest it wasn't doing her much good anyway.

Tests on Sue's arms at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois showed few signs of stress, according to The Field Museum in Chicago, where this giant beast dominates the museum's main hall. The tests suggest that when this fearsome predator was alive more than 65 million years ago, she didn't use those itty-bitty arms very often, museum scientists said.

"It's very early yet, but it seems like there aren't many signs of stress on the bones that would indicate frequent use," Peter Makovicky, associate director of dinosaurs at the museum, said in a statement. "Based on what we know now, it looks like T. rex didn't use its arms much, at least not as an adult, but there's still a lot to learn." [Image Gallery: The Life of T. Rex]

Tiny T. rex arms

T. rex's comically small front limbs have long stumped scientists. Some have argued that the arms had a purpose, pointing out that the bones are short but thick and could have supported bulging muscles. Others think the arms were basically vestigial (a small remnant of an ancestor). T. rex wasn't the only carnivorous dinosaur to have stubby limbs. An allosaur called Gualicho shinyae discovered in Argentina this year also had surprisingly small arms for its body size. G. shinyae is only distantly related to T. rex.

The finding shows that "tyrannosaurs' [arms] really aren't unusual," biologist Thomas Carr told Live Science when the allosaur discovery was announced. "It's not just a one-off [finding]," he said.

New scans

Sue the T. rex was unearthed in Montana in 1990. She's 40.5 feet (12.3 meters) long and 13 feet (4 m) tall, and her skull alone weighs 600 lbs. (270 kilograms). Sue's jaw is pockmarked with holes that may have been caused by a parasitic infection. If so, the disease was serious and may have killed the mighty predator.

But it's Sue's arms that are getting all the attention now. This month, researchers removed the arm bones from the skeleton and transported them to the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. This instrument creates extra-bright X-rays, which researchers are using to study where muscles would have attached to the bone and where blood vessels would have penetrated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Understanding the fine internal morphology of the skeleton will give us clues about how the arm could move and what it was used for," paleontologist Carmen Soriano, a scientist at the Advanced Photon Source, said in a statement released Oct. 12.

The final results of the scans are months away, according to the statement.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.