Future of Health Care: Data Can Empower Patients, Obama Says

To really improve health care for Americans in the future, people must be given more power over their own health data, President Barack Obama said Thursday (Oct. 13).

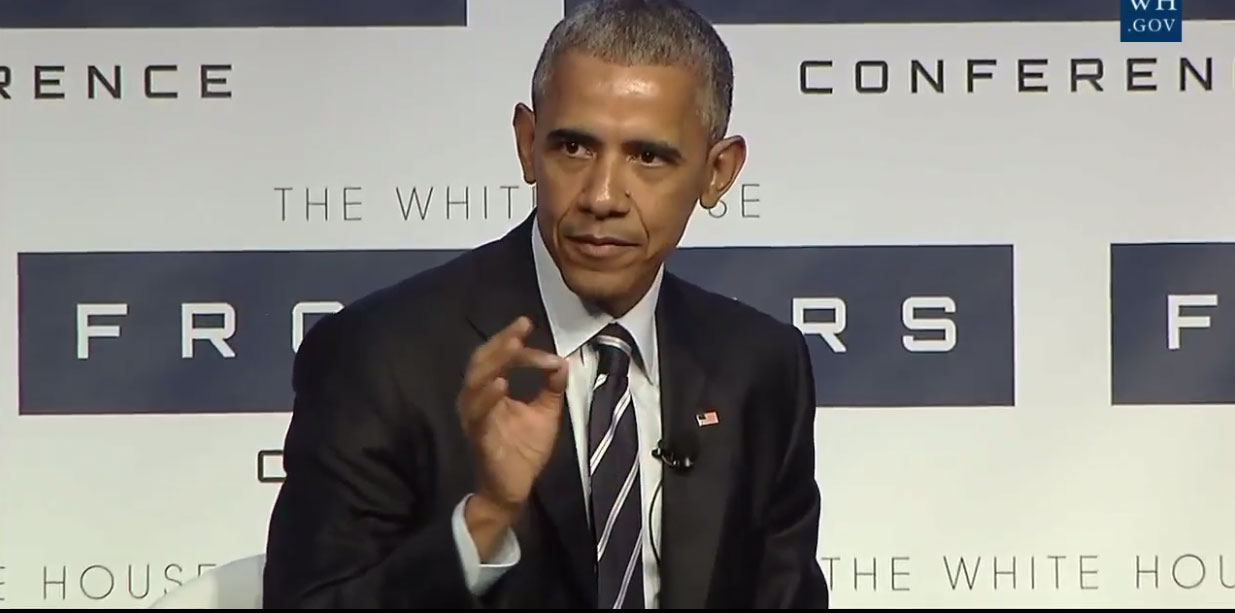

Speaking at the White House Frontiers Conference, an event that focuses on how the U.S. can harness science and technology to improve lives, Obama discussed the importance of opening up health data systems. When people have more information, they feel empowered, and they "don't just feel like cogs in [a] system," Obama said.

"We're trying to promote the notion that this data belongs to you, the patient, as opposed to the institution that is treating you," Obama said, speaking on a panel about health information. "Once you understand that it's yours and you have agency [i.e., power], as you consult with doctors, you're able to be a more effective advocate" for your health, he said.

An important step will be to make it easier for health systems to share an individual's health data, Obama said. Currently, many systems use software that makes it difficult for health care providers to share information, so patients end up going from doctor to doctor, filling out forms to give the same health information. [10 'Barbaric' Medical Treatments That Are Still Used Today]

Another panelist, Zoë Keating — a cellist, composer and patient advocate — spoke about her frustrating experience with the health care system when her husband was diagnosed with lung cancer and was treated at multiple institutions. She described a system that felt "fractured, impersonal and cruel."

"During our journey, we never had a sense that there was one person keeping track of all the data," Keating said.

The panel was related to Obama's Precision Medicine Initiative, which aims to usher in an era of medicine that "delivers the right treatment at the right time to the right individual," based on their genes, environment and lifestyle, according to the White House. Obama discussed how the goal of the initiative is not just to develop innovative new treatments, but also to improve people's lives.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What we've been calling this Precision Medicine Initiative is really, how do we stitch together systems that can maximize the potential of the research" that scientists are doing "and end up with Zoë's husband getting better treatment?" Obama said. "At the end of the day, they're people, who count."

On the research side, the initiative is working toward creating large databases that scientists can use to share data. This means that, instead of individual institutions studying diseases by themselves, researchers will be able to pool and synthesize large amounts of data from many institutions, which will hopefully accelerate research and innovation, Obama said.

For example, using this data may allow researchers to identify genes that predispose people to specific diseases, and then find ways to intervene before these diseases develop, Obama said.

Still, once researchers have this information, it will be important to figure out how to get it to patients quickly, "to empower them so they can be in charge of their own health," Obama said.

The Frontiers Conference kicked off with an announcement of more than $300 million in federal and private funding for various projects in science and technology. This includes $16 million toward the Precision Medicine Initiative, and $70 million for the BRAIN Initiative (which stands for Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies), which aims to improve scientists' understanding of the human brain, according to the White House.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.