Denali Dinos: Ancient Bones Are First of Their Kind in National Park

Alaska's majestic Denali National Park is home to North America's tallest mountain and a wide array of wild animals, including moose, wolves and grizzly bears. But now, scientists have concrete evidence that the park was once home to an entirely different set of creatures: dinosaurs.

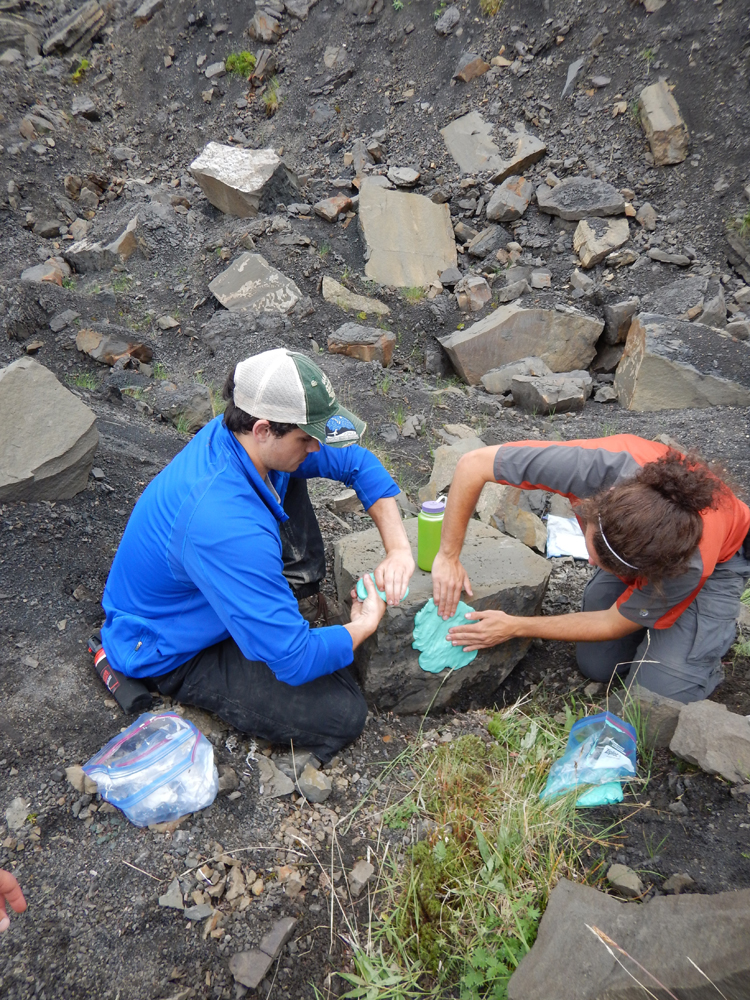

Researchers found the fossilized bones of what they think are dinosaurs during a July 2016 expedition that included paleontologists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) and the National Park Service, according to an online announcement that was made Tuesday (Oct. 18). The group also discovered several new dinosaur trackways — fossilized impressions of footprints left by dinosaurs that once walked though mud that later turned into rock.

"This marks the beginning of a multiyear project to locate, document and study dinosaur fossils in Denali National Park," Pat Druckenmiller, the leader of the collaborative dinosaur project and a curator of earth sciences at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, said in a statement. [See Photos of the Dinosaur Discovery in Denali]

They found a total of four bone fragments — the largest of which is just a few inches long — that seem to be parts of larger bones that belonged to a big beast, and not to a smaller mammal, bird or even a flying reptile, the researchers said. The specimens also resembled other plant-eating dinosaur bones found in other parts of Alaska, the researchers said.

The microstructure of one of the specimens — a large fragment of spongy bone — indicates that it isn't from a crocodile or slow-growing, cold-blooded (also known as ectothermic) animal, the researchers said. And a preliminary analysis of the shape and structure of another of the specimens, an ossified tendon, indicates that the fibrous connective tissue may have belonged to a large ornithopod dinosaur, likely a duck-billed dinosaur, Druckenmiller said.

In fact, among large dinosaurs, duck-billed dinosaurs (also called hadrosaurs) were probably the most common to live in Alaska during the Cretaceous period, the researchers said. The climate was warmer back then, but still chilly, suggesting that dinosaurs could survive in cooler conditions, team member Gregory Erickson, of Florida State University, told Live Science in 2015.

In 2005, UAF students found Denali's first known dinosaur trackway in the Cantwell Formation near Igloo Creek. Paleontologists have discovered thousands of dinosaur tracks since then, including those of hadrosaurs, also known as duck-billed dinosaurs, but they had yet to find any dinosaur bones, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other dinosaur trackways that have been found in Denali National Park over the years belong to ceratopsians (a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that includes triceratops), therizinosaurs (bipedal herbivores) and flying reptiles known as pterosaurs, Erickson said.

However, no dinosaur bones had ever been found in the park, until now. "Now that we have found bones, we have another way to understand the dinosaurs that lived here 70 million years ago," Druckenmiller said.

To learn more about the fossils, Erickson, who studies dinosaur bone and tooth structure, is now cutting some of the fossils into microscopically thin slices so that he can analyze their internal architecture.

Once he examines these thin sections under a high-powered microscope, Erickson will be able to identify what kind of animal left the bones behind. Moreover, the bones' growth lines, which are similar to tree rings, will reveal how fast the animals grew and how old they were when they died.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.