Photos: 500 New Methane Seeps Off the Pacific Northwest Coast

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Cascadia Margin

An exploration of the Cascadia margin between British Columbia and Northern California this summer aimed to map methane seeps in the region. Scientists aboard the Research Vessel Nautilus captured this seafloor image of a flounder and friend in June 2016 during a remotely operated vehicle dive.

[Read full story on the discovery of methane seeps]

Champagne bubbles

The camera of a remotely operated vehicle launched from the Research Vessel Nautilus captures methane bubbles rising from a seep in Cascadia. Researchers exploring this region in June 2016 discovered about 500 previously unknown methane seeps, doubling the amount known to be along the U.S. West Coast.

Sea life in Cascadia

Starfish and other sea life on the ocean floor near newly discovered methane seeps in the Cascadia region. Methane seeps attract methanophiles, or organisms that live off the hydrocarbon gas. They thus form the basis of largely unexplored ocean ecosystems.

Researchers aboard the Nautilus took temperature readings and seafloor and water samples from the seep site, as well as samples from bacterial mats growing around the seeps.

Close-up on a seep

A close look at a Cascadia methane seep reveals sea life — and, sadly, seafloor litter. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas produced both by microorganisms living under the ocean floor and by geological processes as buried organic material decomposes under pressure. Little is known about the sources of the methane seen here.

Crabby creatures

A remotely operative vehicle camera captures a yellow crab and starfish on the seafloor in the Cascadia margin. This area is a geologically active subduction zone where the oceanic crust is pushing under the less dense continental crust of North America.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

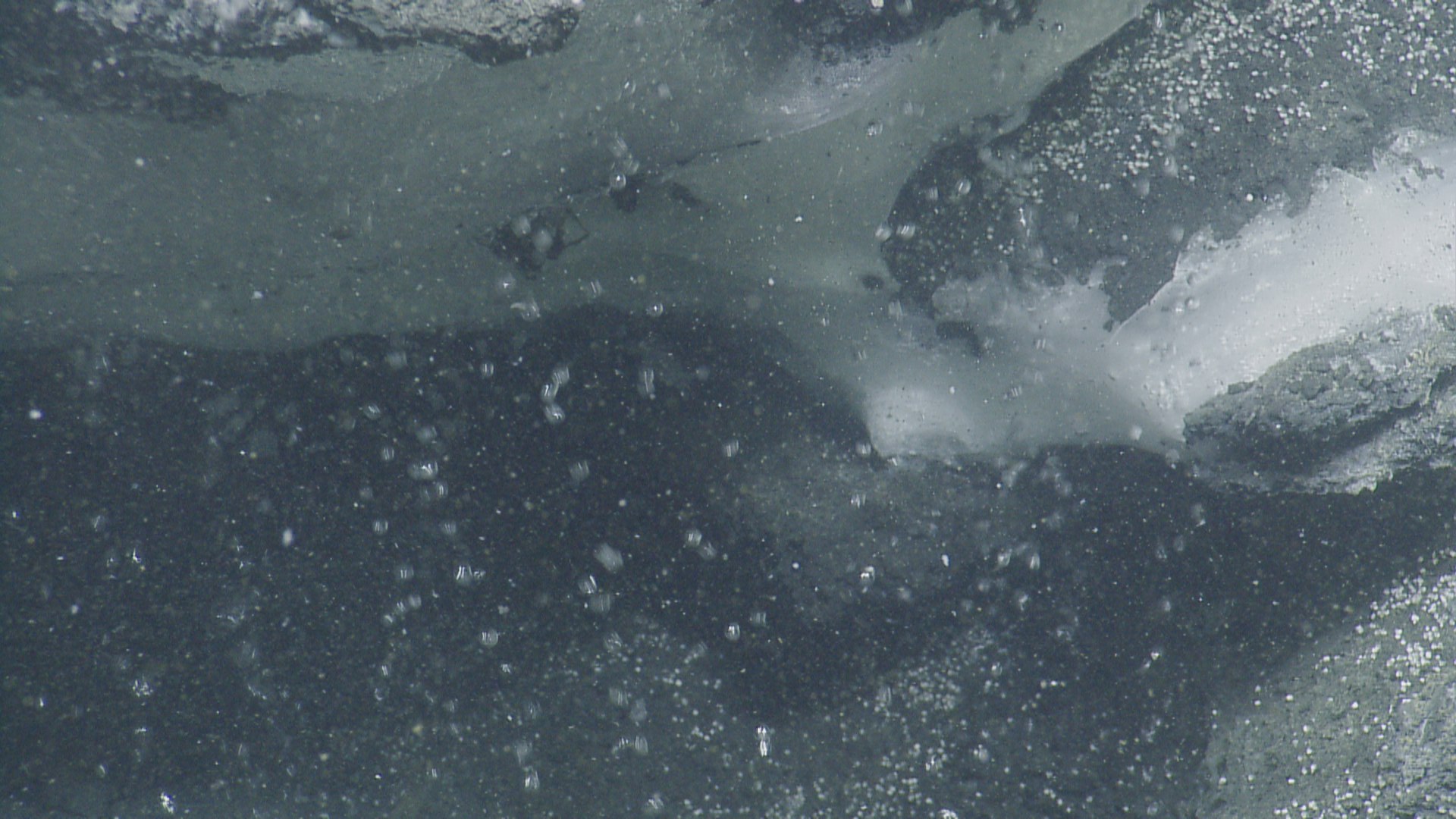

Icy environment

Methane ice lines a newly discovered methane seep off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. This ice is known as methane clathrate or methane hydrate, and it's made of methane molecules trapped between molecules of water. Around the seeps are bacterial mats made of organisms that live off the methane gas.

Researchers discovered the bubble plume from this seep using sonar. The seep is in the middle of the Astoria submarine canyon, an unexpected spot for such a seep, according to researchers with the Ocean Exploration Trust.

Bubbles and dots

Methane bubbles, many surrounded by a skin of icy methane hydrate, flow upward from a seep in the Astoria submarine canyon. The white dots on the ocean floor were a mystery to researchers aboard the Nautilus, who collected some for analysis.

Reach for the stars

Starfish along the floor of Astoria canyon off the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

Drifting through

The research scientists aboard the research vessel Nautilus saw animals swimming and drifting through the methane bubbles streaming from the seafloor in the Cascadia margin near Oregon and Washington. The scientists aren't sure why animals would be passing through the methane bubbles, but one researcher aboard Nautilus suggested they could be consuming bacteria coming from the seeps.

[Read full story on the discovery of methane seeps]

Champagne bubbles

The methane bubbles streaming up from the seafloor off the Pacific Northwest coast appeared almost like champagne bubbles.

The researchers watching the camera feed from their ROV commented on how many bubbles they were seeing at these seeps, with plenty of "wow" comments.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus