Snakes Used to Have Legs and Arms … Until These Mutations Happened

The ancestors of today's slithery snakes once sported full-fledged arms and legs, but genetic mutations caused the reptiles to lose all four of their limbs about 150 million years ago, according to two new studies.

The findings are welcome news to herpetologists, who have long wondered what genetic changes caused snakes to lose their arms and legs, the researchers said.

Both studies showed that mutations in a stretch of snake DNA called ZRS (the Zone of Polarizing Activity Regulatory Sequence) were responsible for the limb-altering change. But the two research teams used different techniques to arrive at their findings. [Image Gallery: Snakes of the World]

According to one study, published online today (Oct. 20) in the journal Cell, the snake's ZRS anomalies became apparent to researchers after they took several mouse embryos, removed the mice's ZRS DNA and replaced it with the ZRS section from snakes.

The swap had severe consequences for the mice. Instead of developing regular limbs, the mice barely grew any limbs at all, indicating that ZRS is crucial for the development of limbs, the researchers said.

"This is one of many components of the DNA instructions needed for making limbs in humans and, essentially, all other legged vertebrates. In snakes, it's broken," the study's senior author Axel Visel, a geneticist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, said in a statement.

Pinpointing ZRS

Visel and his colleagues began looking at the genomes of "early" snakes that were closer to the base of the snake family tree — such as the boa and python — that have vestigial legs, or tiny bones buried within their muscles. The scientists also studied "advanced" snakes, including the viper and cobra, which do not have any limb structures.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During their investigation, the researchers focused on a gene called sonic hedgehog, which is key in embryonic development, including limb formation. Sonic hedgehog's regulators, located in the ZRS sequence of DNA, had mutated, they found.

However, the researchers needed proof that the ZRS mutations were responsible for limb loss. To find out, they used a DNA-editing technique called CRISPR (short for "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats") to cut out the ZRS stretch in mice embryos and replace it with the ZRS section from other animals, including snakes.

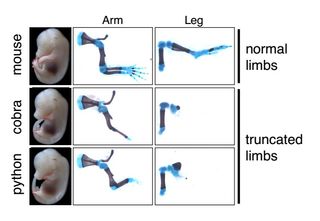

When the mice had ZRS DNA from other animals, including humans and fish, they developed limbs just like any regular mouse would. But when the researchers inserted the python and cobra ZRS into the mice, the mice's limbs barely developed, the researchers found.

Next, the researchers took an in-depth look at the snakes' ZRS, and found that a deletion of 17 base pairs (that is, paired DNA "letters") within the snakes' DNA appeared to be the cause of the limb loss, they said. When they painstakingly "fixed" the mutations in the snake ZRS and inserted it into mice embryos, the mice grew normal legs, they found. [Photos: Weird 4-Legged Snake Was Transitional Creature]

However, creatures usually have redundant DNA that protects against mutations such as these, so it's likely that multiple evolutionary events led to limb loss in snakes, Visel said.

"There's likely some redundancy built in the mouse ZRS," he said. "A few of the other mutations in the snake ZRS probably also played a role in its loss of function during evolution."

Snake femurs

Adult snakes don't have limbs, but extremely young snake embryos do, according to the other study, published online today in the journal Current Biology.

Like the researchers of the Cell study, the scientists found that snake ZRS had disabling mutations that prevented limb development. However, they also found that during the first 24 hours of their existence, python embryos have a "pulse of sonic hedgehog transcription [the first step of gene expression] in just a few limb bud cells," said the study's senior author Martin Cohn, a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

But that transcription switches off within a day of the egg being laid, meaning that the snake cannot fully develop legs, Cohn and his co-author Francisca Leal, a doctoral student in Cohn's lab, found.

"Python ZRS proved to be very inefficient, turning on transcription for a short time in a few cells," Cohn said.

However, even during that short time, python embryos managed to begin development for leg bones such as a femur, tibia and fibula, the researchers found. "[But] those distal structures degenerate before they fully differentiate into cartilage, and python hatchlings are left with just a rudimentary femur and a claw," Cohn said. He added, "the results tell us that pythons have retained a lot more of the leg than we appreciated, but the structures are transitory and are found only at embryonic stages."

Cohn called the Cell study, "a tour de force" and "absolutely thrilling."

"The two groups took very different approaches to the question of limb loss in snakes," Cohn said. "Axel [Visel]'s group started with genomics, and we started with developmental biology, and the two groups converged on exactly the same discovery."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular