18th-Century Scottish Epic Reveals Ties to Ireland

In 1760, Scottish poet James Macpherson published a volume of poems he claimed to have translated from the Gaelic works of a third-century Scottish bard named Ossian. The poems were an enormous hit and a major inspiration to the nascent Romantic period in literature and art.

They may also have been fakes — or, at least, far less authentic than Macpherson claimed. Early critics, including English poet Samuel Johnson, pointed out the poems' similarities to Irish mythology and that Macpherson never produced any ancient documents indicating the origin of the works.

Now, a new analysis of the relationships among the characters in the "Ossian" poems suggests they share more in common with their Irish cousins than their author would have liked to admit. The social structure of the world of "Ossian" is more similar to that seen in Irish mythology and less similar to that seen in the Homeric epics that Macpherson touted as being similar to the Scottish work. [Top 10 Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth]

"It shows a similarity to the works he's trying to distance himself from, and it shows a distance from the works that he's trying to associate himself with," said study author Justin Tonra, a researcher in digital humanities at the National University of Ireland Galway.

Centuries of controversy

When Macpherson published his epic, the British army had just defeated the claimant to the English throne, Charles Stuart and his Jacobite supporters, and Scottish culture was being suppressed in an effort to instill loyalty to Great Britain. Macpherson's translations were thus a matter of national pride, and he strove to compare his epic to the works of Homer, Virgil and other highly regarded Classical sources.

Over the past 250 years, the debate over "Ossian" has evolved from a black-and-white "Were the tales of 'Ossian' real, or did Macpherson make it all up?" to a more nuanced conversation about oral history, mythology and Macpherson's input as an author, Tonra told Live Science.

"Our sense is that Macpherson did collect narratives and took down oral poems [around Scotland] and used them as sources," Tonra said. "He would have also used older manuscript sources that were available in libraries in Scotland. He takes these sources but applies this quite modern slant to them that is his own particular style." [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

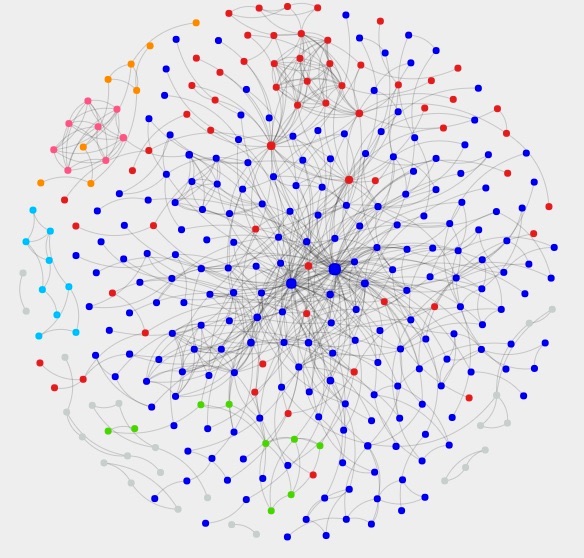

Tonra and his colleagues — including some who work in statistical physics, about as far from the literary discipline as you can get — joined forces to conduct what's known as a network analysis on the earliest versions of the Ossian poems. This kind of analysis essentially quantifies all of the relationships in an epic poem and characterizes them as positive or negative. The result is a spider-web-like visualization of the society depicted in the poems.

"You can't get a comprehensive picture of network structure from just reading the narrative, because there are too many characters," Tonra said.

Comparative literature

The researchers compared the "Ossian" network structure to those in Homer's "Iliad" and "Odyssey" as well as to the "Fenian Cycle" of Irish mythology, a series of poems about the Irish warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill.

The 748 relationships among 325 characters in the Ossian created a network more like those in the Irish myths than the Homeric epics, the researchers found. (The difference comes down to the probabilities that nodes representing characters will have small or large numbers of relationships, or "edges.") The paper, available on the preprint website arXiv, was published Oct. 19 in the journal Advances in Complex Systems.

The analysis can't definitively prove whether Macpherson was intentionally fraudulent when he published the "Ossian," Tonra said, but it does show that the Irish influence is strong.

"There is potentially some subconscious element of the Irish narratives that transfers to Macpherson's own," Tonra said. "Or it may tell us that this story does travel between the two Celtic nations."

Macpherson argued that the Irish tales were adapted from Scottish myth, while many Irish critics argue vociferously that it was Scotland who borrowed the myths from Ireland. The direction of the travel isn't clear, but the desire to assert a national identity remains strong 250 years later, Tonra said.

"While we were doing this research earlier this year and late last year, the whole Brexit debate was happening, and Scottish identity was reasserting itself as not really in tune with the larger beliefs in the U.K.," Tonra said, referring to the vote over whether the United Kingdom should leave the European Union. Scotland voted to stay 62 percent to 38 percent, and Northern Ireland also favored staying in the E.U., though the overall U.K. vote was to leave.

"It really stuck me," Tonra said, "that there are continuing echoes of these national identities, particularly of the Celtic nations."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.