Ancient Teeth Show Early Human Favored Right Hand

Nearly 2 million years ago, an early human used a stone tool to carve hunks of meat held in its mouth, an activity that left behind wear marks in its teeth.

And the direction of the grooves suggest that this individual had a dominant right hand.

Right-handedness is significantly more common than left-handedness in modern humans, and the trait emerged early in the lineage's evolution, researchers have said. This discovery, which presents the oldest evidence of right-handedness, could prompt a deeper look into the fossil record, to determine when human ancestors first demonstrated right-handed dominance. [The 10 Biggest Mysteries of the First Humans]

Right-handed "handy man"

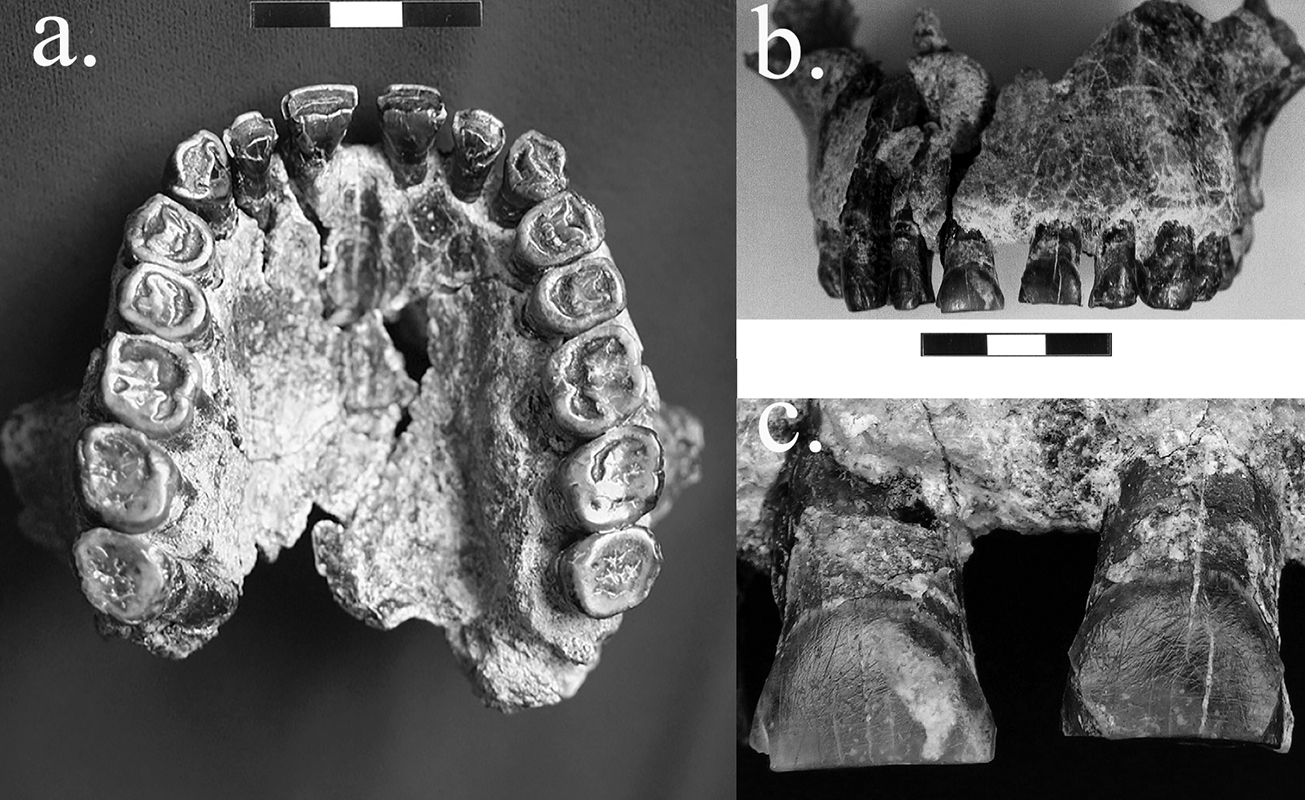

The fossil, a mostly intact upper jaw, was found in an archaeological dig site in northern Tanzania, in a location with stone tools and large mammal bones nearby. The jaw belonged to Homo habilis, a human ancestor that lived 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago and is the oldest known ancestor in the Homo lineage.

Homo habilis means "handy man," and though the newly discovered specimen's hands were nowhere to be found, its jaw and teeth provided researchers with unexpected evidence of whether it was a so-called "righty" or "lefty."

The teeth were very well-preserved, with enamel still covering most of their surfaces. Close inspection of two central incisors in the jaw revealed concentrations of scratch marks; in one tooth in particular, they were primarily angled to the right side of the body.

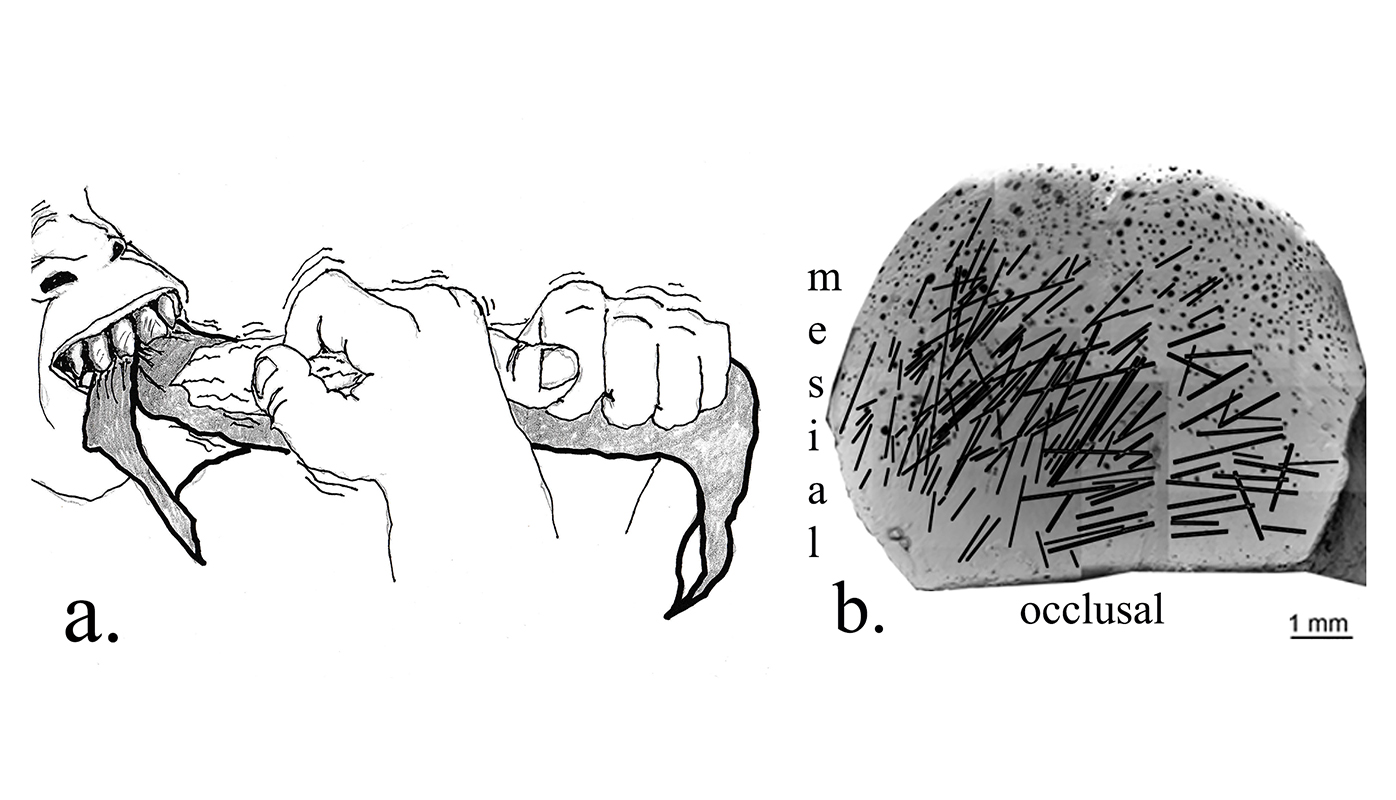

According to the scientists, these marks were created over time, as the "handy man" was cutting up his meat. He would have gripped a hunk of flesh in his mouth, steadied the meat by pulling on it with one of his hands and used the other hand — which was probably the dominant one — to saw pieces of meat with a stone tool, which would occasionally scrape against his teeth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The right-leaning direction of these scrapes — which have also been detected in fossil teeth belonging to Neanderthals and other human relatives — told the scientists that a tool held in the right hand had made the marks.

"Righty" vs. "lefty"

Humans aren't the only mammal species that favors one hand over the other; this trait appears in animals "from kangaroos to chimpanzees," the study authors wrote. However, having a dominant hand that appears overwhelmingly across an entire species is uniquely human; 90 percent of people today are right-handed, the researchers estimated, compared with 50 percent of individuals in humans' primate relatives.

But when did humans first develop a preference for using the right hand over the left? Fossil arm bones might hold clues, but researchers would need both arms from a single individual to tell which hand the individual used more often in life, and that's proven hard to find in the fossil record.

However, this new discovery suggests that scientists could find the evidence preserved in fossil teeth, which are more plentiful than matched pairs of arm bones, the researchers said. While this is as yet the only example of dominant hand use in humans' early lineage, other fossils may provide the clues researchers need to trace the origins of "righty" vs. "lefty," the scientists said.

The findings were published online in the November issue of the Journal of Evolution.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.