Early humans may have hunted cave lions for their sleek pelts, which could have pushed the big cats in the region to extinction, new research suggests.

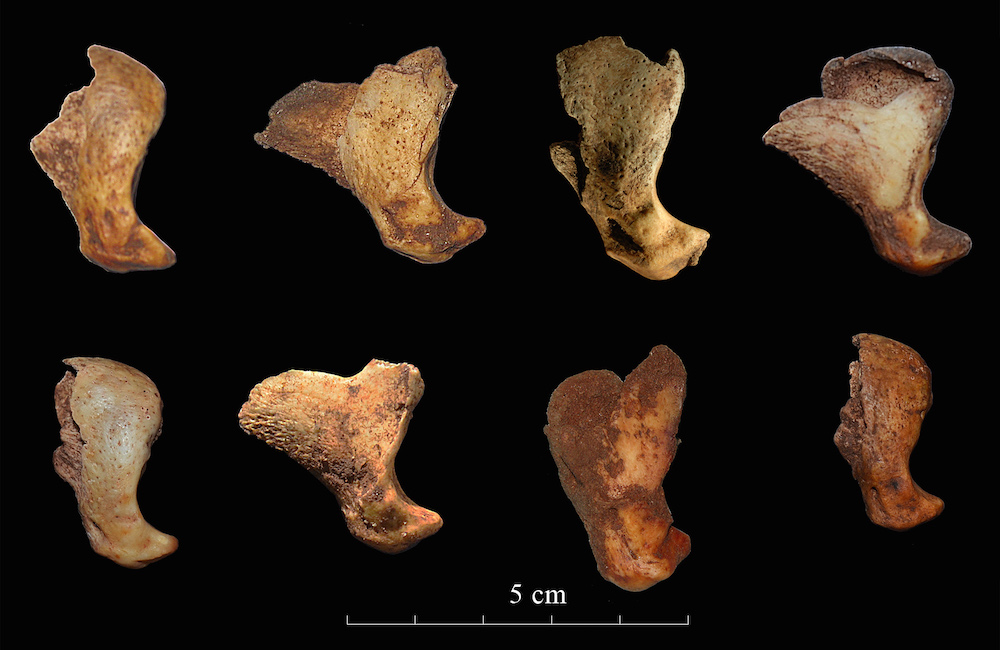

Cave lion fossils were found in a Spanish cave called La Garma, which contains well-preserved artifacts from tens of thousands of years of human occupation. Cut marks on the claws looked similar to marks seen on the bones of animals after they have been skinned for their pelts, the researchers found.

"We have found claw fossils that belong to one individual and can be related with the skinning process in a ritual context," study co-author Marian Cueto, an archaeologist at the University of Cantabria in Spain, wrote in an email to Live Science. [6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

Ancient beast

The Eurasian cave lion (Panthera spelaeus) was one of the largest lions to ever stalk the Earth. The cave lion's ancestor split off from its smaller African lion cousin about 700,000 years ago and at its peak, the cave lion ranged throughout much of Europe and Alaska. It went extinct in Europe about 14,000 years ago, and the last cave lion died in Alaska about 1,000 years later, according to a 2011 study in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The new fossils came from a cave in the Cantabrian Mountains. The site, La Garma, is a vast, multilevel cave with human burial sites in the upper levels and animal bones in the lower level. Archaeologists have found some traces of human habitation going back 70,000 years, as well as painted depictions of animals. A rock collapse blocked the entry to the cave's lower level, preserving it from changes over the millennia.

"It's like a time machine. When you walk into the cave it is like traveling back in time to a specific moment in our evolution," Cueto said.

The team found the cave lion claws, which date back about 14,000 years, in this lower level. When they analyzed them closely, they found the claws had cut marks typical of the process used to separate the claws from the rest of the foot, the researchers reported today (Oct. 26) in the journal PLOS ONE. This same process is used today to declaw house cats in veterinary procedures, the researchers wrote in the paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The marked cat claws suggest humans hunted the animals and displayed or used their pelts. One possibility is that the pelts had some ritual significance, Cueto said.

The "lion is a difficult and dangerous animal to hunt, and it probably had an important role as [a] trophy," Cueto said. In many historical societies, wearing or using a carnivore pelt was a symbol of power, she added. Another site in Germany has yielded cave lion teeth that were used as ornaments or tools.

The date of the claws suggests they may have come from one of the last cave lions to have prowled the area. That in turn may implicate human activities, such as hunting, in the animals' extinction, the researchers wrote in the paper.

"Humans could have played a much more active role in the extinction of this animal. It is not the only cause for the cave lion extinction, but it is a determinant one," Cueto said, referring to human activity.

However, other clashes between humans and cave lions may have also pushed the animals toward extinction. For instance, cave lions like to rear their cubs in the same caves that humans increasingly occupied in the thousands of years before the animals' disappearance, Cueto said. That may have hurt the animal's reproductive success.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.