Revenge Killings: Irreverent Burials Suggest Ancient Blood Feuds

Ancient corpses dumped haphazardly into desert graves near the U.S.-Mexican border may have been victims of blood feuds between and within communities, a new study finds.

Practices for dealing with the dead worldwide have varied greatly over time, ranging from burials above and below ground to funeral pyres, burial at sea, and even the ancient Tibetan practice of "sky burial." In this method, corpses are placed on mountaintops to decompose while exposed to the elements or to get eaten by vultures.

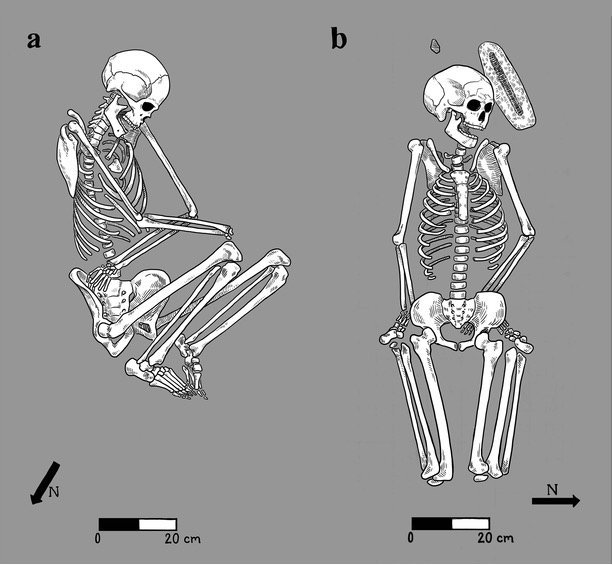

Still, previous research found that ancient funerals in the Sonoran Desert, which straddles the United States and Mexico, were generally similar to what they are today worldwide. Bodies of the deceased were laid to rest respectfully, with the bodies situated on their sides in a flexed position. Sometimes, people were even interred with items such as seashells, bone tools, stone pipes and quartz crystals. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

However, study lead author James Watson, a bioarchaeologist at the Arizona State Museum and the University of Arizona, Tucson, and his colleagues had discovered that in some cases, burials in the Sonoran Desert received much less reverent treatment. Instead, these bodies were tossed haphazardly into graves, sometimes after apparently experiencing violent deaths.

"These people were buried very differently than the rest of the community, and we're trying to understand why that is," Watson said in a statement.

Haphazard burials

Watson and his colleagues investigated more than 170 burials in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico dating between 2100 B.C. and A.D. 50. The sites were unearthed over the course of about 20 years.

Working in the Sonoran Desert means dealing with heat, "and there are plenty of venomous animals, but it's a pretty lush desert, which was successfully farmed for thousands of years to the present," Watson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

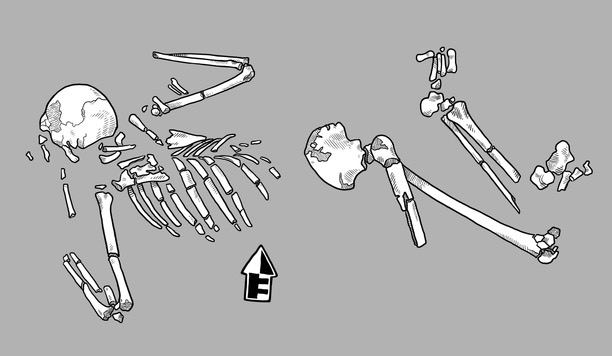

Eight of the burials the scientists examined were atypical, in that the bodies were apparently flung into the graves with no regard for formal positioning of the body. One of these bodies, that of a young man, had four arrowhead-like stone wedges inside of it; another body, that of an older female, had charring on the face and side of the head.

The researchers suggested that the way these eight bodies "were tossed into these pits is a form of continued desecration of the body," Watson said in a statement. "It's moving from violence on the living individual, through to the process of death, to violence on the corpse."

One possibility is that these atypical burials were held for those accused of witchcraft. However, based on previous research in those cases, "one might expect those individuals to be dismembered or to have some heavy object placed over their bodies, to keep them from leaving the grave after burial," Watson told Live Science.

Other kinds of atypical burials, such as those that occur with sacrifices or capital punishment, might have more ritual associated with them, Watson said. For instance, "one might expect them to be bound in some way," he said.

Instead, the researchers suggested that the hasty or irreverent disposal they found "means these people may have been the victims of revenge," Watson said.

Violence and revenge

To find out if bloody revenge was to blame, the scientists analyzed 186 societies of varying sizes across the globe. Results showed that revenge was often a significant motivation for violence in the kind of small-scale societies that these bodies likely came from. The researchers suggested "that the violence-revenge cycle results in blood feuds and can lead to desecration of individuals at and after the time of death, which is what is contributing to these atypical burials," Watson said. [The History of Human Aggression]

Watson's research focuses largely on the changes that took place as the ancient peoples that lived in the Sonoran Desert adopted farming. The researchers suggested that as communities in this area shifted to agriculture, "there was tension both within and between communities," Watson said. "Violence was a big part of that transition around the world."

To explain the desecration of these graves, Watson pointed to a concept from evolutionary biology known as "costly signaling theory." This idea suggests that animals may behave in ways that are simultaneously advantageous and risky; for instance, male birds often have colorful plumage that attracts both mates and predators. Similarly, a disrespectful burial may have sent a message that strongly asserted power and dominance, but also ran the risk of retaliation from the families and friends of victims, the researchers suggested.

"People are very hesitant to apply biological models to human behavior, since there are a lot of complexities when it comes to understanding humans," Watson said. "That said, we are also animals, and I think in some cases, it's appropriate to apply biological models."

Although this work focuses on violence that happened thousands of years ago, Watson said the research might also help people understand modern-day violence.

"With some of the issues that we're seeing today — like increased violence and murders in a lot of cities, police shootings, retaliation upon police — a lot of kids are growing up in a culture of violence in certain communities, and they're learning different values on how to interact with their environment because of the disadvantages that they have," Watson said in the statement.

"They gain status because they're good at being violent; that's how you gain respect. Then, along with that comes advantages — wealth, women and offspring, potentially. There is a biological imperative to signal that they are worthy of the status they're trying to earn."

Watson and doctoral student Danielle Phelps at the University of Arizona detailed their findings in the October issue of the journal Current Anthropology.

Original article on Live Science.