Deadly Measles Complication More Common Than Doctors Thought

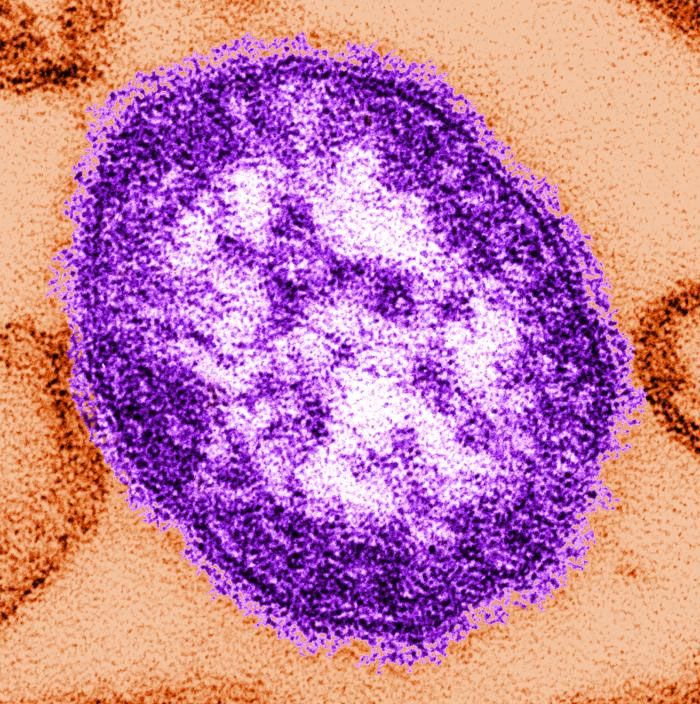

NEW ORLEANS — A deadly complication of the measles, which can occur years after a person is infected with the virus, is more common than researchers previously thought, according to a new study.

The complication, called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), is a progressive neurological disorder that involves inflammation in the brain. People with SSPE die, on average, within one or two years of being diagnosed with the disease. Some people may live longer, but the condition is always fatal, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Previously, researchers thought the risk of post-measles SSPE was one in 100,000, according to the study. But the new analysis suggests that kids who get the measles before age 5 have a one in 1,387 chance of developing SSPE, and kids who get the measles before age 1 have a one in 609 chance. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

In the study, the researchers looked at all of the cases of SSPE in California that occurred between 1998 and 2015, identifying 17 cases. The children were diagnosed with SSPE, on average, at age 12, the researchers found. However, some children were diagnosed when they were as young as age 3, and others, as old as age 35.

When someone gets sick with the measles, the body usually rids itself of the virus in about 14 days. In rare cases, however, the virus can spread to the brain but go dormant. Scientists don't know why the virus becomes active again, but if it does, it leads to SSPE.

SSPE is thought to occur in three stages, study senior author Dr. James Cherry, a distinguished research professor of pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said at a press conference today (Oct. 28), here at IDWeek 2016, a meeting of several organizations focused on infectious diseases.

In the first stage, a person with SSPE may act a little differently, Cherry said. If the patient is a child in school, he or she may not do as well, or may act aggressively, Cherry said. The behavioral changes can be subtle, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the second stage of SSPE, a person will have seizures, Cherry said. These seizures can be subtle at first; for example, a person may faint, but in fact he or she is having a seizure, Cherry said. As the disease progresses, the seizures become more common and more pronounced, he said.

In the final stage, seizures occur constantly, and the person eventually becomes comatose, Cherry said.

Of the 17 cases of people with SSPE identified in the new study, 16 have died and one person is receiving hospice care, Cherry said.

The new findings are "really frightening," Cherry said.

The results also highlight the need for the measles vaccine, said Dr. Gary Marshall, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Kentucky, who was not involved with the study. "It's unconscionable that we're talking about a completely preventable cause of death in children," he said.

Indeed, the measles vaccine is the only surefire way to prevent this type of infection, Marshall said.

However, because the first dose of the measles vaccine isn't given until a child is between 12 and 15 months old, children younger than 1 year are susceptible to the disease.

To protect these children, as well as people who, due to medical reasons, can't be vaccinated, everyone else needs to get the vaccine, Cherry said. This would create herd immunity, he said.

Herd immunity is what protects babies, Marshall said at the press conference. But there's a threshold to herd immunity, he added. If the proportion of people who are vaccinated dips below a certain rate, herd immunity no longer comes into effect, he said.

The new findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Originally published on Live Science.