Polarizing Politics: 5 Reasons the 2016 Election Feels So Personal

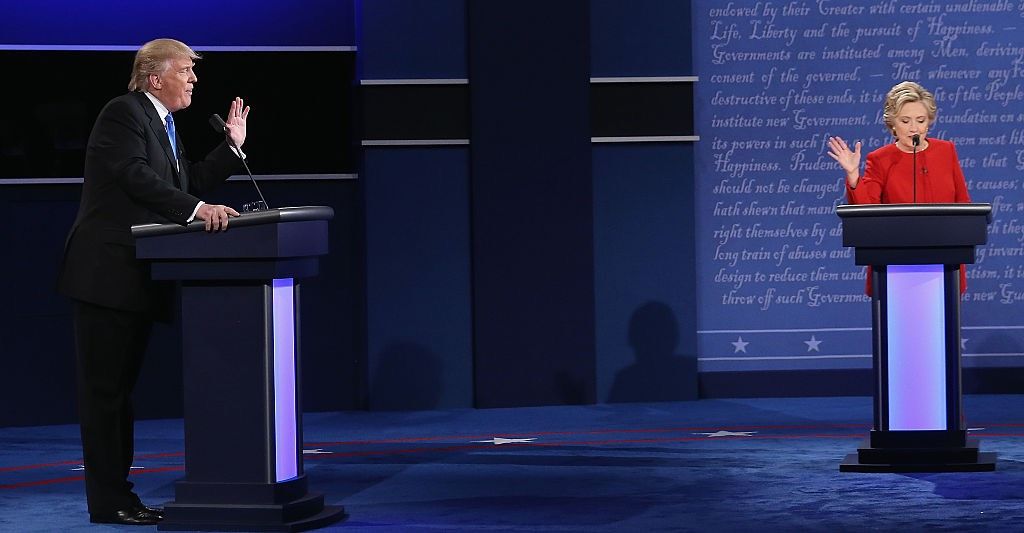

This year's presidential campaign has been rough. At rallies for Republican candidate Donald Trump, crowds chant, "Lock her up!" in reference to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. Trump, meanwhile, has been accused of groping and sexually harassing multiple women. Clinton has called some of his supporters "deplorable," while Trump has called Clinton a "nasty woman."

Anecdotal evidence suggests that this negativity is trickling down. Across social media, people publicly announce their plans to unfriend acquaintances on the other side. Friendships and marriages that have weathered years of political differences suddenly seem on unstable ground, according to social media posts, surveys and news articles. In early August, The New York Times profiled a couple who was split between the Trump-Clinton camps. Though the two had been on opposite sides of the 2012 election, this year was the first time one had threatened divorce over the other's vote. [Election Day 2016: A Guide to the When, Why, What and How]

A Monmouth University poll released in September found that 7 percent of Americans said they'd lost friendships over the 2016 election. Experts say there are a lot of reasons for the high emotions on both sides. Here are five major reasons you might find your finger hovering over the Unfriend button before Nov. 8:

1. A deepening partisan divide

The 2016 election is happening against the backdrop of political polarization in the United States. Ordinary Americans are increasingly divided, and increasingly less likely to view the other side with charity. A 2014 Pew Research Center nationally representative survey of 10,000 Americans found that 21 percent eschew consistently conservative or consistently liberal views — an increase from 10 percent in 1994. Thirty-eight percent of Democrats and 43 percent of Republicans viewed supporters of the other party "very unfavorably," up from 16 percent and 17 percent, respectively, in 1994. The two sides even see each other as enemies: 27 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans said the other party threatens the nation's very well-being.

A 2015 study published in the American Journal of Political Science found that open discrimination against the opposing party is stronger than racial discrimination in experimental studies.

"Today, the sense of partisan identification is all-encompassing and affects behavior in both political and nonpolitical contexts," the researchers concluded.

2. Mudslinging candidates

Against this backdrop of distrust and dislike, the 2016 election has served up two incredibly polarizing candidates with extensive public histories. [We Fact-Checked the Science Behind the Republican Party Platform]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Republicans have been very suspicious of Hillary Clinton since she was first lady," said Stanley Feldman, a political scientist at Stony Brook University in New York. Trump's criticism of Clinton — that she is guilty of criminal behavior and shouldn't have been allowed to run — is "largely unprecedented," Feldman told Live Science.

At the same time, Feldman said, Trump is a "lightning rod for very strong feelings," due to comments that have antagonized women and minority groups. The rhetoric around the election has cast each candidate as illegitimate or unqualified, he said, increasing the public's anxiety.

The candidates' behavior also sets a standard for the public's behavior, said Joshua Klapow, a clinical psychologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health.

"It's personal, and that's what they're modeling," Klapow told Live Science. "What's happening is that the concern we have about our country and the passion we may have for our position has gotten much more emotional than intellectual." [How to Argue Politics Without Blowing Up Your Relationship]

3. Hot-button issues

The election has also focused on a number of emotionally charged topics: race, religion, sexism and sexual assault, to name a few.

"One of the potentially disturbing parts of this election is the extent to which — I'll say particularly the Trump campaign — has seemingly made it OK to more directly criticize various minority groups and women," Feldman said. "That has generally been considered to be unacceptable in public discourse."

The breakdown of norms inflames emotions and makes it harder to reconcile across party lines post-election, Feldman said. Racism and sexism also hit close to home for many Americans, who then find it difficult to face friends and family who support a candidate they associate with their own experiences of victimization.

"When he [Trump] opens his mouth and speaks about women the way that he does, I feel the fear and I feel the anxiety from my assault take over, as I'm sure most any sexual assault survivor does," an anonymous author wrote on the parenting blog Scary Mommy.

"It is, for many women, personal, and then they try to scrutinize the motives of people who are saying, 'Oh, it's nothing,'" Feldman said. "That's much harder for people to forget."

4. Existential questions

Americans as a whole have been losing trust in social institutions for decades. A 2013 report from researchers at the University of Chicago found that when asked about 12 institutions — from the Supreme Court, to organized religion, to the medical establishment — only 23.3 percent of Americans reported a "great deal of confidence" in these institutions between 2008 and 2012. That number was down from 29.9 percent in surveys taken during the 1970s.

This confidence level isn't at its lowest point in the past 40 years, however — there was an even lower point between 1993 and 1996, during which only 22.6 percent of Americans had a great deal of confidence in social institutions. The study from 2013 also showed a low level of confidence in Congress, with only 6.6 percent of Americans saying they had great confidence in the legislative body. That same year, 14.3 percent of Americans said they had great confidence in the executive branch.

These confidence issues played out during the primaryelection as well as the general election. During the Democratic National Convention, supporters of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders staged a walkout to protest what they called a "rigged" or broken primary system. Much of Trump's candidacy has been predicated on the impression that the political system is broken.

"Change has to come from outside our very broken system," Trump told a crowd in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, earlier this week. He also repeated accusations that the system is rigged and that voter fraud means election results can't be trusted. In conversations like these — on whether the system is corrupt — there's little room for common ground, Feldman said.

"When you have a situation like this where the candidates are cast as being completely unacceptable, when there are aspersions made about how the system is unfair, it's really hard to see how people are going to walk away from this feeling like, 'OK, we lost, but we can wait four years,'" Feldman said.

5. Social media

Once upon a time, you might not have known the political affiliations of your kid's teacher, your ex-boss, your cousin's fiancé and your friends from the adult softball league. Alas, those days are long gone. Now, the political opinions of people you might never talk politics with are all over Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites.

"It's not uncommon for us now to discover, 'Oh my goodness, I didn't realize he or she thought that way,' based on what they're saying on social media," Klapow said.

The emotional tenor of the election isn't driven entirely by social media, Feldman said, but it isn't helping, either.

"People are increasingly turning to the web, to Facebook and Twitter for the news, and that does run the risk of something like an echo chamber, where people who have these intense feelings just find them reinforced," he said. Whether the next election is as vicious as this one will depend partially on the candidates, he said, but also on the public discourse around the process from journalists, politicians and commentators across the media.

"I'm not optimistic that this polarization is just going to disappear overnight," Feldman said. "It's going to take a lot of work."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.