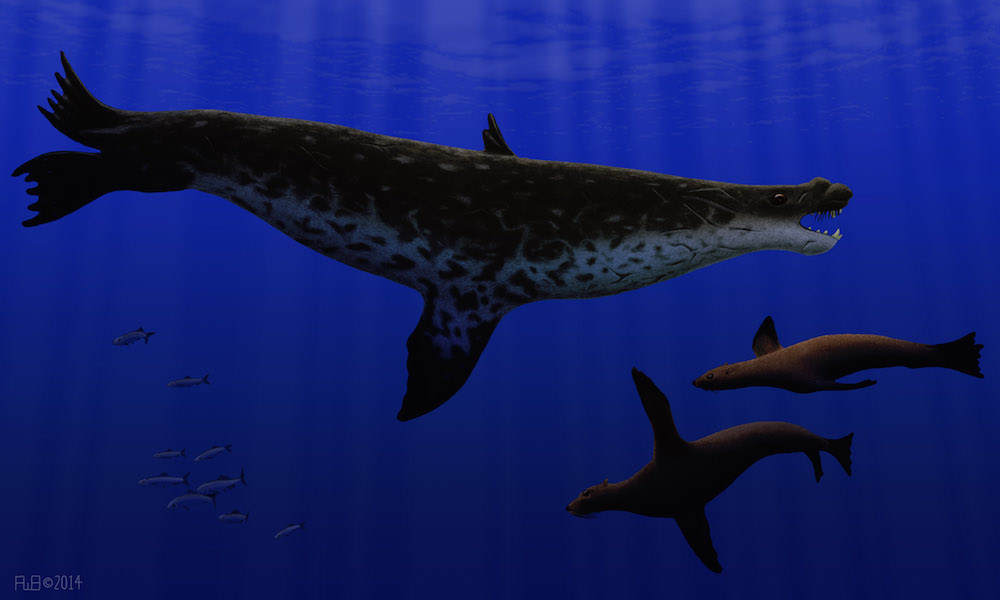

Ancient 'Seal' Used Pool-Ball-Size Eyes for Deep-Sea Hunting

SALT LAKE CITY — About 10 million years ago, a seal-like creature likely dove to the dark ocean floor, using its large, pool-ball-size eyeballs to spot squid and other prey, new research finds.

The ancient creature is a newly identified species of pinniped, a group that includes animals that are fin-footed and semiaquatic, such as seals and sea lions. The seal-like creature is also the youngest known member of Desmatophocidae, a prehistoric family of pinnipeds that went extinct during the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), the researchers said.

"Desmatophocids are probably the only major group of pinnipeds that have completely gone extinct," said study lead author Robert Boessenecker, an adjunct lecturer in the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. "We think of this one as the last straggler."

The newly identified species falls into the genus Allodesmus, but the researchers have yet to give it a species name. At 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) long, the seal would have been about the same size as a modern-day Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus). [Giants on Ice: See Amazing Images of Walruses]

Phil Bigelow, then a master's student at the University of Washington, discovered the Allodesmus in Grays Harbor, Washington, in the early 1980s, and researchers spent about a decade preparing it from its case of "extremely hard" rock, Boessenecker said.

In the end, they uncovered the animal's skull, jawbones (with one preserved tooth), neck vertebrae, part of its sternum and a nearly complete rib cage, Boessenecker said.

They also found that a small shark with serrated teeth, likely a dogfish shark, scavenged the marine beast's skull after it died. The skull had about a dozen bite marks on it, and researchers found about 15 little 0.3-inch-long (8 millimeters) shark teeth at the excavation site, said Boessenecker and his co-author, Morgan Churchill, a postdoctoral student of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, before the animal died and sharks got the best of it, the seal-like creature likely swam around the waters of the northern Pacific, diving deep for food. That's when its big, round eyes came in handy, the researchers said.

"Seals, unlike whales, don't echolocate," or use sound waves to navigate, Churchill said. "One of their main forms of senses when they're hunting, or just navigating underwater, is their eyesight," Churchill added. "And so, they have very large and reinforced eyeballs to help them collect light at these deeper depths."

Based on the large size of the animal's canines and its sagittal crest (a bony feature on the skull that attaches to the jaw muscles), it was likely a male, Boessenecker said. Moreover, because the growth plates are fused on its vertebrae, it's clear that it had reached adulthood, he said.

Like other Desmatophocids, this one's relationship to other pinnipeds is murky. There is no surviving DNA from the group to help scientists put this species firmly on the pinniped family tree. Desmatophocidae might be a sister group to the walrus and sea lion group, or a sister group to true seals, such as the monk and elephant seal, Boessenecker said.

"They are sort of this wild-card group," he said.

The study, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Thursday (Oct. 27) here at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.