Rigging an Election: How Difficult Is It?

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump claims our system of elections are rigged. He has asserted widespread voter impersonation exists. He has claimed that large numbers of dead people vote. And, he maintains that many noncitizens have successfully registered to vote and regularly do so.

Don't believe it.

Our democratic system of government counts on voters rejecting these claims that our electoral outcomes are at risk. Citizen trust in election outcomes and the accurate tabulation of votes is fundamental to the legitimacy of representative government.

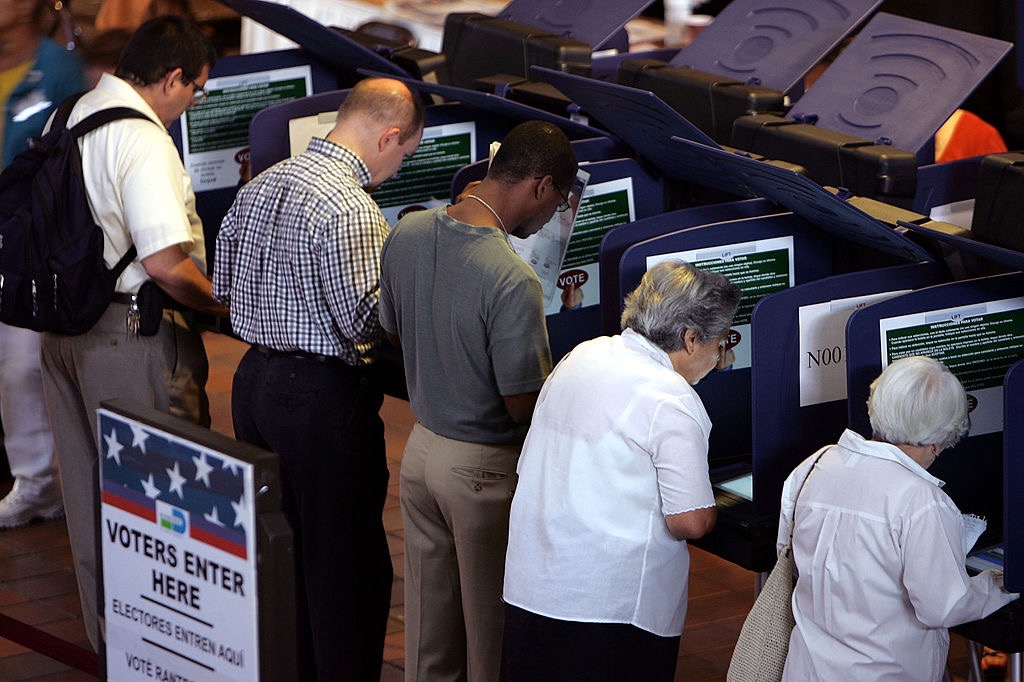

How American elections are administered

As a political scientist who studies election administration and works with election officials to make the voting process successful, I know from firsthand experience that rigging a presidential election would not involve just undermining one system — it involves undermining thousands.

A key feature of the American system of election administration is hyper-localism. More than 5,000 municipal and county election officials administer elections across more than 8,000 local jurisdictions across the United States.

A 2009 survey of local election officials found that about half of local election officials are nonpartisan, meaning they are not Democrats or Republicans. The other half is about evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. In other words, only 25 percent of election officials support either party, significantly limiting the number of potential coconspirators who may back any given outcome.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moreover, the United States Constitution grants broad power to state legislative bodies regarding the regulation of elections. States regulate ballot design, vote tabulation technology, absentee ballots and early voting. This means that someone attempting to rig an election would need to master 50 states' methods of administering elections, including polling place management.

Another roadblock is the sheer number of votes involved. Presidential elections generally prompt higher turnout than any other election. In the 2012 presidential election, 130 million people cast their ballots. President Obama received nearly five million more votes in the popular vote compared to Republican nominee Mitt Romney. The sheer size of the electorate suggests that attempting to "rig" the system would require a level of coordination even greater than the coordination needed to "get out the vote" on Election Day itself.

Voters who know their history may be under the impression that influencing the popular vote isn't really necessary. In 2000, Palm Beach County Florida played an outsized role in the outcome of the presidential election. That year, as few as 537 votes divided Vice President Al Gore from then Texas Gov. George W. Bush. Those few votes had the power to decide into whose column Florida would fall, and which candidate would win the Electoral College.

This recent history may tempt voters to think that would-be riggers need to tamper with the outcome in only one county to change the vote. Yet, nobody could have reliably predicted that Palm Beach County would be the lynch pin in 2000. The odds of a state result within half a percentage point – close enough to trigger a recount – are only about 7 percent, according to the website fivethirtyeight.com.

Let us examine each type of rigging method Trump identifies as a problem.

Rigging by voter impersonation

Voter impersonation involves casting a fraudulent ballot.

One could do that by getting a group of people to register to vote multiple times under false names. In this way, a single person could pretend to be more than one person and go to several polling locations to cast several ballots.

Alternatively, one could get a group of people to go to multiple polling locations, pretend to be someone else and hope that someone else had not yet voted and would not vote later in the day.

In either case, the costs of voter impersonation are high not only because of the risk of arrest for illegal activity, but also because actually engaging in such activity requires extensive planning, time and travel cost.

Although many Americans believe that voter fraud is "very common," it is, in fact, rare.

The famed urban machines at the turn of the century like New York City's Tammany Hall were often accused of controlling electoral outcomes through fraud and manipulation at the polls, but much of the evidence for stolen elections is largely anecdotal in nature.

When fraud is attempted now, as it apparently was during Iowa's early voting period, the system worked to stop the attempt.

Election law scholars, including University of California Irvine School of Law's Richard Hasen, Rutgers' Lorraine Minnite and Loyola Law School's Justin Levitt, have searched to find evidence of large-scale fraud and come up empty-handed.

"There is … no evidence in at least a generation that [voter impersonation fraud] has been used in an effort to steal an election," Hasan has written. "The reason voter impersonation fraud is never prosecuted is that it almost never happens."

Rigging by impersonating deceased voters

Trump also claims that dead people vote.

Here, the concern is that deceased people remain on voter registration lists after their deaths, permitting living people to impersonate them and vote in their place.

It's certainly true that inaccuracies exist on the voter rolls. According to a Pew Center on the States issue brief, voter registration lists across the 50 states suffer from inaccuracies largely because of they have "not kept pace with advancing technology and a mobile society."

In many states, for example, registration information is entered into computers manually. When people move, even within a state, their voter registration does not move with them. When a citizen changes his or her address with one government agency, that information is not communicated to the election department. Citizens need to reregister to vote every time they move. The report states that "1.8 million deceased individuals are listed as voters." To put that number in context, 2.4 million U.S. residents die each year.

The question then turns to how an organization, person or political campaign interested in perpetuating fraud could turn these 1.8 million deceased voters into votes.

Bad actors would have to proactively locate the deceased voters – focusing on key states or even counties – and then impersonate them to successfully turn an election.

Does it happen? The evidence is scant. According to a report from New York University's Brennan Center investigating voter fraud, the vast majority of cases in which allegations of fraud by dead voters are asserted end up being clerical errors when voter lists are matched against death lists.

Rigging by having noncitizens vote

Trump has also asserted that noncitizens have successfully registered to vote and will be able to successfully cast ballots during the 2016 election.

Here we need to look at motives. The costs associated with attempting to register and vote as a noncitizen are high, including criminal prosecution and deportation. The reward of committing such fraud for the individual noncitizen is simply the addition of one vote. A campaign would need to convince hundreds or thousands of noncitizens to take this substantial risk to influence the outcome in even one county – and then keep quiet about it.

According to the Brennan Center, no documented cases exist in which individual noncitizens have "either intentionally registered to vote or voted while knowing they were ineligible."

All of this adds up to a system of election administration that is virtually impossible to penetrate in the name of massive fraud that would shift the results of an election. So don't believe it when someone tries to tell you the vote is rigged.

Rachael V. Cobb, Associate Professor of Government and Chair of the Government Department, Suffolk University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.