How Did the Milky Way Get Its Name?

If you look upward on a clear night from Earth's darkest regions, you'll probably glimpse a broad stripe of stars, cloaked in clouds of dust and gas, arcing across the sky.

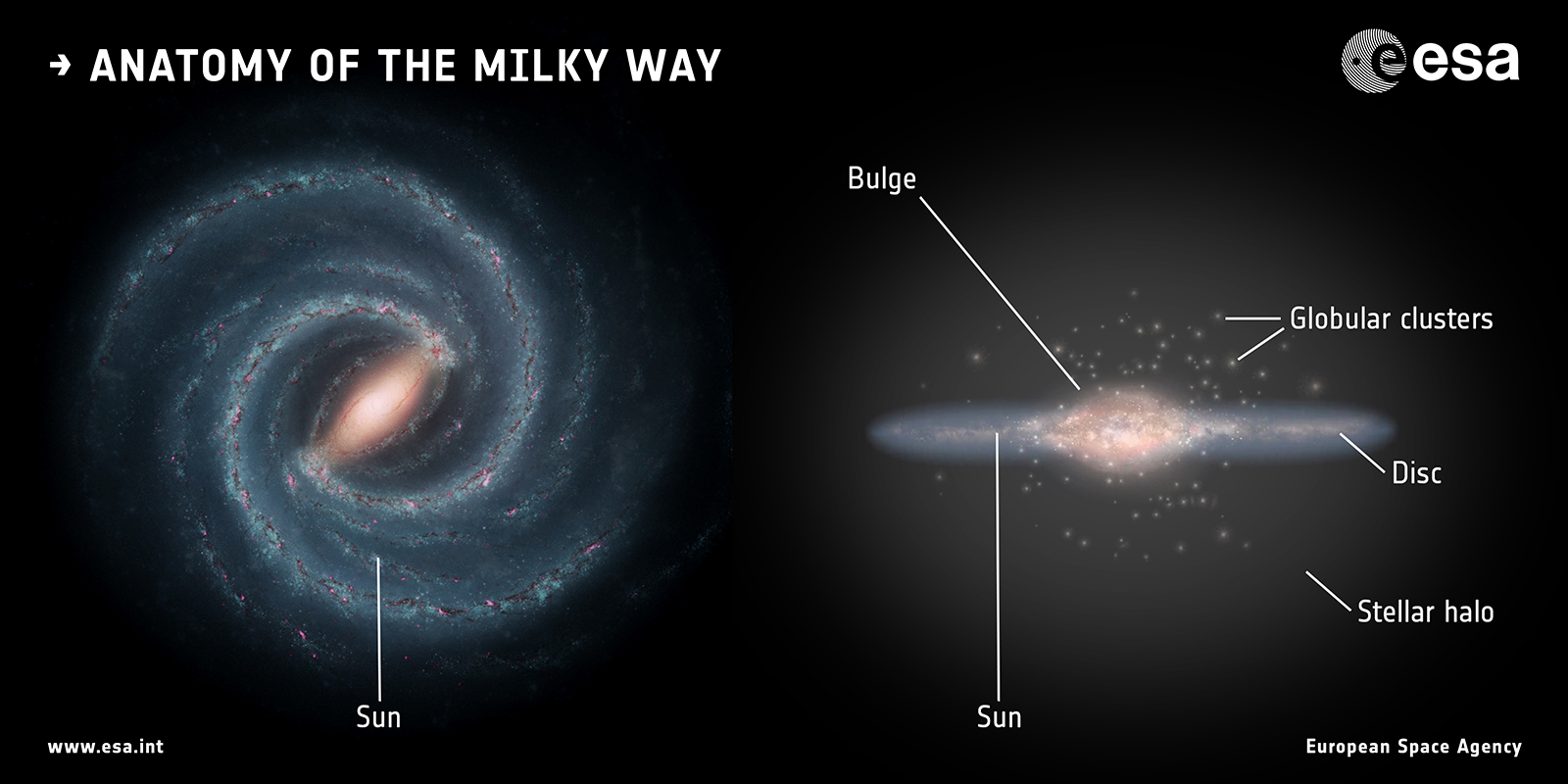

What you're seeing is a portion of the Milky Way, our home galaxy, which measures 100,000 light-years in diameter. (A light-year is the distance light travels in one year — almost 6 trillion miles, or 9.5 trillion kilometers.) Its core hosts a supermassive black hole — a giant gravitational field so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape — and its multiple "arms" that spiral from the center hold hundreds of billions of stars, one of which is our own sun.

The Milky Way is estimated to be 13.2 billion years old, and is one of many billions of galaxies in the known universe. Other galaxies may be older and bigger, but as Earth's cosmic address, the Milky Way has long fascinated humans. It was recognized by astronomers thousands of years ago, and ancient civilizations featured it in their mythologies. But how and when did this galaxy get its unusual name in the first place?[8 Galaxies with Unusual Names]

The Roman poet Ovid wrote about the Milky Way in "The Metamorphoses," first published in A.D. 8, saying, "There is a high track, seen when the sky is clear, called the Milky Way, and known for its brightness."

The earliest mentions of the Milky Way can be traced back to the ancient Greeks (800 B.C. to 500 B.C.), according to Matthew Stanley, a professor of the history of science at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University. But it's unclear exactly when the name emerged, he told Live Science.

"The term was in common use in Western astronomy 2,500 years ago," Stanley said, referring to stargazers in European countries. "So there's no way of knowing who first coined it and how it first came to be. It's one of those terms that's so old that its origin is generally forgotten by now."

In fact, Stanley added, the Milky Way provided astronomers with the Greek root for the astronomical term "galaxy."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"'Galactos' literally means 'the milky thing in the sky,'" Stanley said.

The Greek myth about the Milky Way's formation was immortalized by Renaissance artist Jacopo Tintoretto in the painting "The Origin of the Milky Way," around 1575. Tintoretto likely based his artwork on a version of the story that appeared in the 10th-century folklore text "Geoponica," according to the National Gallery, where the painting is displayed. The legend described the god Zeus bringing an infant Hercules to his sleeping wife Hera's breast so the baby could nurse secretly. When Hera awoke and pulled away, her breast milk sprayed into the firmament and created the Milky Way. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)]

But although early astronomers may have observed the Milky Way, they didn't quite know what to make of it. Prior to the invention of telescopes at the start of the 17th century, galaxies were known as nebulae, perplexing, cloudy regions that didn't behave like other visible objects, such as stars and planets.

"They were accepted as anomalies that you have to watch out for and not get distracted by, but they got little attention," Stanley said.

That all changed when Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope at the sky in 1609, and discovered that some of the puzzling cosmic dust clouds were made up of stars grouped closely together.

"This is the key moment for the realization that nebulae are something interesting, that they're structures of their own that can be studied," Stanley told Live Science. "That's when people start giving them particular names because they recognized shapes in them, and they realized they could have some cosmic significance."

However, most galaxies don't get descriptive names because there are simply far too many of them. The number of known galaxies continues to grow as technology improves scientists' ability to discover even very faint objects from the universe's infancy — by some estimates, the total could be as high as 200 billion. The vast majority of galaxies, once astronomers note their locations, are identified by a number following a letter or letters that indicate their position in a catalog of celestial objects.

And with the discovery of so many other galaxies, astronomers have learned that the Milky Way, despite being our home galaxy, is just not that special.

"The basic assumption is that our galaxy is totally ordinary," Stanley said.

Ordinary it may be, but the sight of the Milky Way — even a partial view from Earth or from space — is still awe-inspiring, and can help people to understand and to appreciate our place in the universe, and to recapture a little of the wonder experienced by the first astronomers who peered up at the sky thousands of years ago.

"Whoever named the Milky Way did so through standing in darkness, night after night, gazing up at our own galaxy and trying to name that feeling of being one with the cosmos," Stanley said.

"There's something extraordinary and sublime about standing on a mountaintop and seeing the vastness of our own galaxy wrapping around us," he added.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.