Images: Animal Tales Illuminate the 'Aberdeen Bestiary'

The Aberdeen Bestiary

The book, the "Aberdeen Bestiary" was published in England around the year 1200. First documented in 1542 in the Royal Library at Westminster Palace, the medieval manuscript is lavishly illustrated with gold leaf and detailed images of animal scenes. The book is meant to illustrate moral beliefs through animal stories. Now, the University of Aberdeen has used high-resolution photography to enhance and digitize every page of the book, revealing features that were invisible to the naked eye.

Here's a look at some of those lavishly illustrated pages.

[Read full story on the Aberdeen Bestiary]

Pelicans

The three scenes in this image, called The Pelican, show baby pelicans attacking their parents, who in turn kill the babies. Then, the mother pelican pierces her side and the resulting blood flows over the dead babies, who then return to life, according to the University of Aberdeen. "Possibly the idea of mother pouring sustenance over her babies comes from the birds' habit of regurgitation," according to the university.

Part of the translation reveals the morality aspect of this manuscript: " Thus after three days, it revives its young with its blood, as Christ saves us, whom he has redeemed with his own blood. In a moral sense, we can understand by the pelican not the righteous man, but anyone who distances himself far from carnal desire."

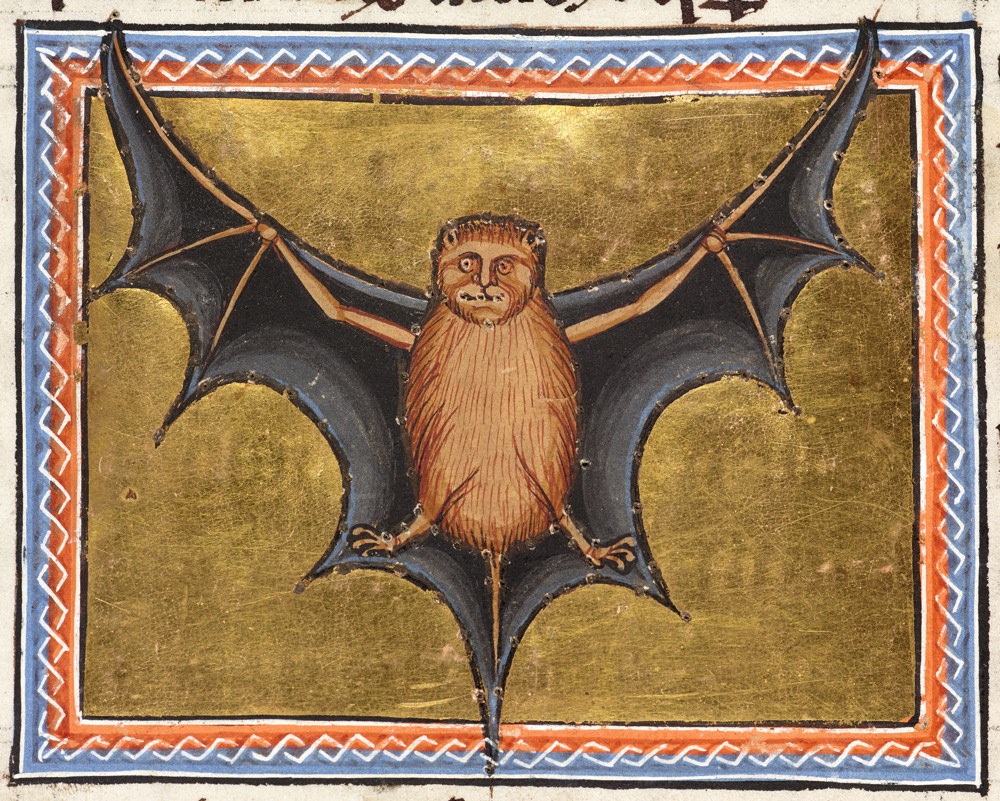

The Bat

The illustration of the bat "is a fairly accurate ventral view of a bat whose wings are shown as a membrane stretching from its three fingers down to its toes and tail," according to the University of Aberdeen. Prick marks are visible and reveal a technique called "pouncing" was used to transfer the image to other pages.

Tiger cub

In this illustration, a horseman, after stealing a cub, is being chased by a tiger. To trick the tiger, the horseman throws down a glass sphere. The tiger sees its own reflection, and thinking it is her cub, she stops to nurse the sphere. In the end, the tiger mother loses her cub and her revenge.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Glass sphere

The glass sphere seems to be pained with tarnished silver, the University of Aberdeen noted. Evidence of pricking on the image suggests it was transferred to other sheets. "Tiny prick holes are placed around several of the animals," lead researcher Jane Geddes, an art historian from the University of Aberdeen, told Live Science. "Blank sheets would be placed under these holes, and charcoal sprinkled over the top, as a simple form of transfer."

Bestiary star

Here, a decorative star in the "Aberdeen Bestiary."

[Read full story on the Aberdeen Bestiary]

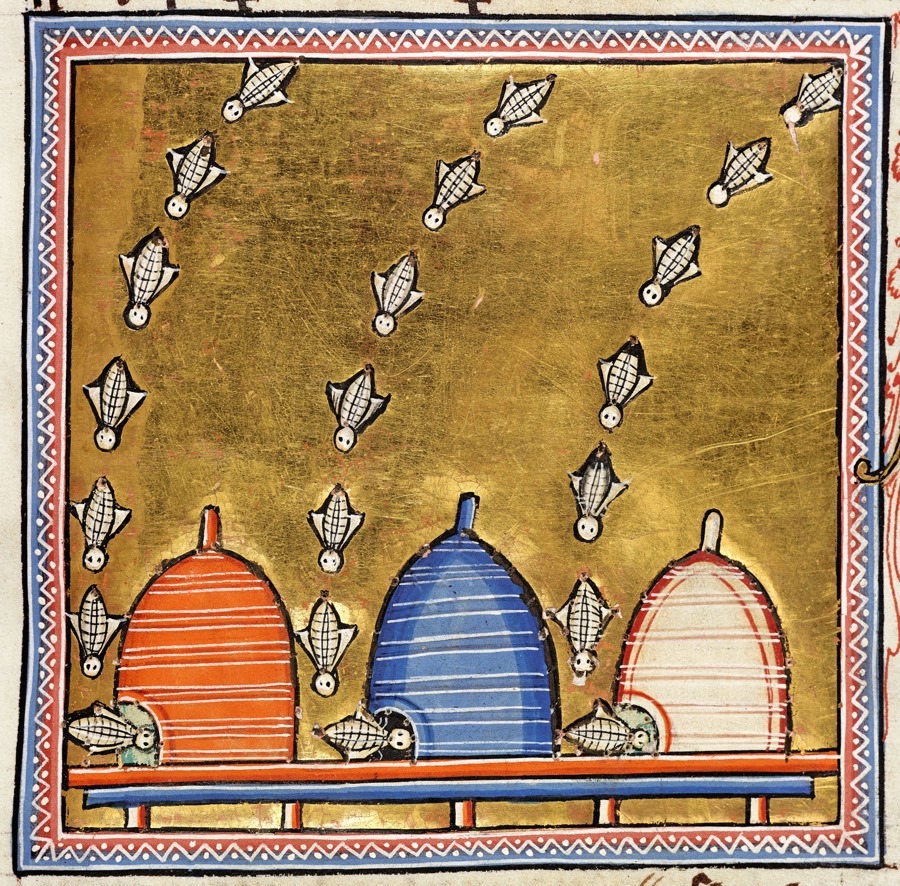

Orderly bees

In this illustration, three identical bees each zoom into their hives, made of coiled straw, in three orderly rows. "The design emphasises their collective labours and orderliness. The bees look like a combination of hand grenades and shuttlecocks. They should have a head, thorax and abdomen, and four wings," according to the University of Aberdeen.

Part of the translation of this tale reads: "Bees, apes, are so called either because they hold on to things with their feet, or because they are born without feet (the Latin word for 'foot' is pes). For afterwards they acquire both feet and wings. Expert in the task of making honey, they occupy the places assigned to them; they construct their dwelling-places with indescribable skill, and store away honey from a variety of flowers."

Blind mole

This blind mole has no eyes and the illustration showed signs of pouncing for transferring the image to another sheet. Part of the translation reads: "The mole is called talpa because it is condemned to darkness by its permanent blindness. For it lacks eyes, eyeless, is always digging in the ground and throwing out the soil, and feeds on the the roots of the plants which the Greeks call aphala, vetch," according to the University of Aberdeen.

Silver dove

This silver-colored dove illustration shows a "rather lifeless bird," notes the University of Aberdeen. Part of the translation of this animal tale reads: "From these wings spring feathers, that is, spiritual virtues. These feathers gleam with the brilliance of silver, since word of their renown has the sweet ring of silver to those who hear it," according to the University of Aberdeen.

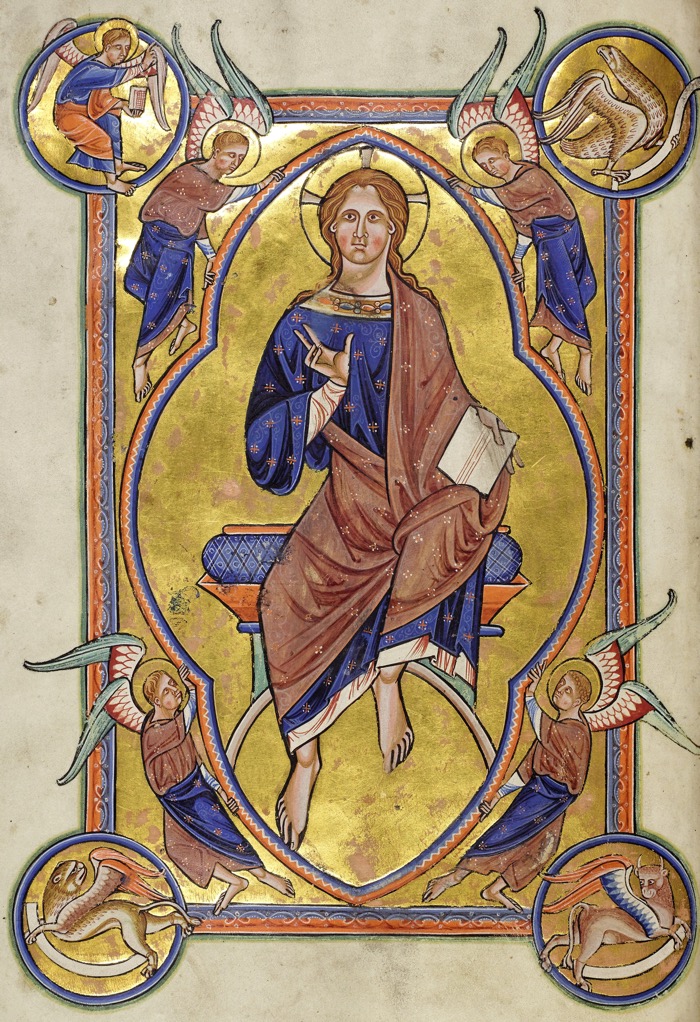

Christ in Majesty

There is no text on the page showing the illustration of "Christ in Majesty." In this image, Christ is seated on a throne within a quadrilobe mandorla, or a four-lobed pointed oval shape, with is feet on a rainbow. The mandorla is supported by four angels. The image "reflects the eternity and immanence of God's creation," notes the University of Aberdeen.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.