Why Not Paper Ballots? America's Weird History of Voting Machines

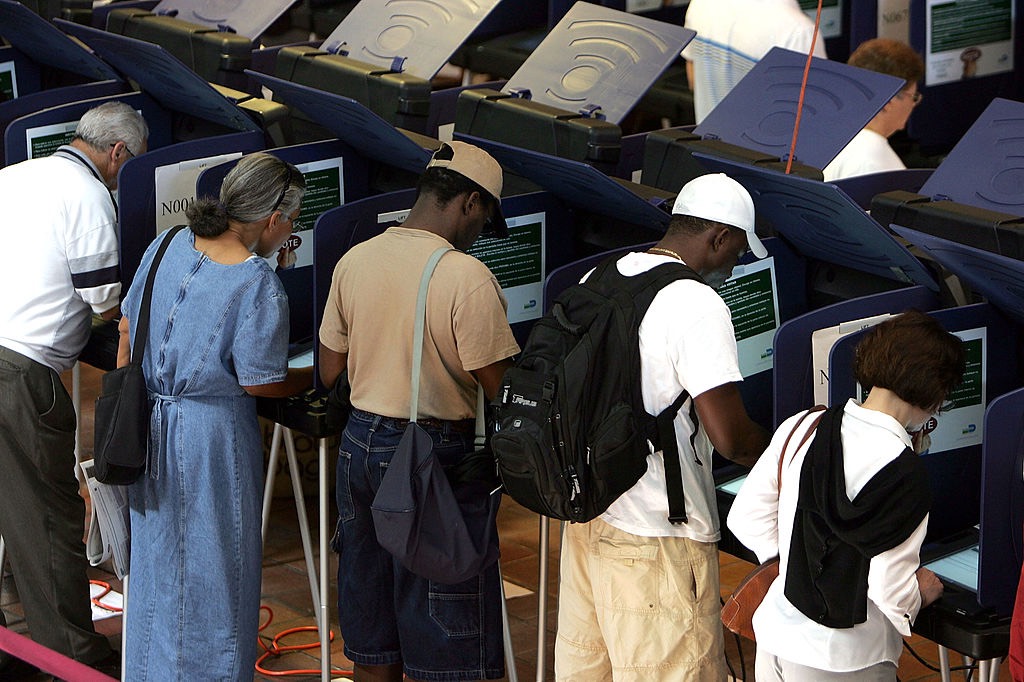

Americans heading to the polls today (Nov. 8) might vote using punch-card ballots, optically scanned paper ballots (which are generally handwritten) or computerized systems that record votes. In a few districts (mostly small and rural), voters might fill out an old-fashioned paper ballot and put it in a box.

Those who voted before 2010 might remember the old lever machines.

In the U.S., the hodgepodge of voting methods has a long and odd history, one determined by the sometimes conflicting needs of counting votes accurately, preventing election fraud and checking the accuracy of total counts. Because voting procedures are left up to individual states, it gets even more complicated, according toWarren Stewart, communications director at Verified Voting, a nonpartisan group that tracks voting technologies. [How Are Votes Counted?]

The voting-machine idea started in Britain, with the Chartists. Followers of a working-class movement, the Chartists believed in such radical (for the1830s) concepts as universal male suffrage, secret ballots and voting districts that were based on population size, each containing an equal number of people. And it was the Chartists who first proposed a voting machine, which consisted of a brass ball that a voter would drop into a hole for the relevant candidate. The ball would trip a mechanism that would count a vote for that person.

It's not clear that such machines ever caught on. But the proposal suggests that people were thinking about secret ballots and properly counting votes while preventing frauds.

Secret ballots were introduced to the U.S. in the 1890s, in part to combat vote-buying (a common practice in the 19th century, when many votes were announced verbally and parties printed their own ballots), according to several historians. It worked, to a point. But putting ballots in a box to be hand-counted was, and still is, cumbersome.

"The advantage was that everyone is on an identical ballot and they all look the same," said Warren Stewart, communications director at Verified Voting, a nonpartisan group that tracks voting technologies. [Election Day 2016: A Guide to the When, Why, What and How]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Edison's voting machine

It wasn't long before the introduction of the first voting machines. According to Bill Jones' 1999 report "History of Voting Systems in California," among the very first voting machines emerged in 1869, from none other than Thomas Edison. In 1888, Jacob Myers patented an automatic voting machine, which was first used in Lockport, New York, in 1892. In 1905, Samuel Shoup patented his version of a voting machine.

The two companies, Shoup Voting Machine Corporation and Automatic Voting Machine Corporation dominated the market in the U.S., and Shoup's machines – if slightly updated versions -- were in use all the way until the 2000s in some precincts (New York phased them out only in 2010). If you've ever used one of the old "lever machines," odds are it was one of these two types.

The lever machine tabulates votes using a system of gears. The problem is that there is no way to audit them, Stewart said. While it is possible to tamper with one of these devices — it would have to be done machine by machine — the real problems have more often been simple malfunctions. "Someone could get a piece of pencil lead in the gears and some votes wouldn't be counted," he said.

So while elections using these machines were less vulnerable to tampering and counting was mostly accurate, it was near impossible to check for any mechanical or other problems. [Clinton or Trump for President: What Happens If the Election Is a Tie?]

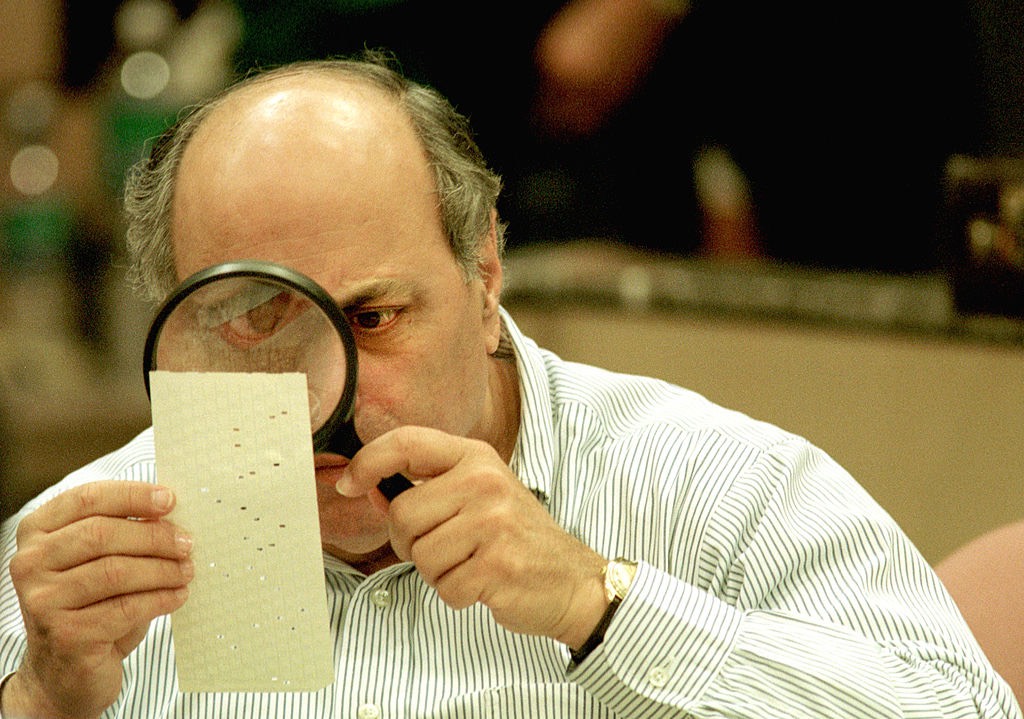

In the 1960s, the punch cards arrived. To vote with these ballots, individuals use a stylus to punch a hole next to each candidate of choice. California had these in the early 1990s, for example. While the cards were often derided after the debacles in 2000 involving "hanging chads" in Florida, these voting tools were the very latest in technology a half-century ago, Stewart noted.

They have been largely phased out, but they made counting easier, and as the election of 2000 showed, they could be audited. Punch cards have been completely phased out, according to Verifiedvoting.com's data; the Pew Research Center notes that only two counties in Idaho still used them in 2014 before eliminating them.

The next step was the optical-scan machine. Scanners are simple: The voter fills in a bubble next to the candidate's name (or ballot measure) on a paper ballot and feeds the ballot into the scanner. The scanner reads and then counts the votes. The advantages are that this machine takes just seconds to use, the device is mostly accurate and the votes can be audited because there are paper ballots for review. Stewart noted that some 80 percent of U.S. precincts use these optical scanners.

Voting on computers

Only recently have computerized voting machines — the ones that record votes directly into a computer's memory — come into vogue. (Such machines are called "direct recording electronic voting machines," or DREs.) The problem is that one can't guarantee that the software is doing what it is supposed to do. "Some election officials liked them because it eliminated paper," which cut costs, Stewart said.

Once touch-screen machines were introduced in the 1990s, it didn't take long for manufacturers to realize that they could sell more of them than the optical-scan machines, according to Stewart. The reason is that an optical scanner requires only that the voter fill in the bubbles and put the ballot in the machine. People can fill out their ballots, pop them in and be done in seconds. It's easy to fill out a ballot while the person ahead is sliding the paper into the scanner.

Touch-screen machines, though, require that the voter make selections right there, so while a person votes, a machine is tied up. That means that a precinct has to order a number of these machines in order to keep the lines from getting too long, Stewart said.

Such computerized systems were beset with problems even when the manufacturers meant well, Stewart noted. In 2002, the Help America Vote Act earmarked a lot of money for updating voting technology, and not every company that made voting machines was necessarily expert in the necessary systems.

Problems cropped up when hackers would demonstrate vulnerabilities, as at this August's Black Hat conference, when researchers from Symantec showed that tampering with an individual voting machine could be done using a $15 device. Last year, Wired.com reported that Virginia decertified electronic touch-screen voting machines because they were too vulnerable to attacks over their Wi-Fi connections.

Optical-scan machines made a comeback in the wake of the problems discovered, so for the most part, voters will see the optical-scan machines, as various districts have re-instituted them. That said, the touch-screen machines, for example, are still used in 30 states. Some areas have touch-screen machines equipped with "voter-verified paper audit trail printers" (California and Colorado, for example). However, other states, such as Florida, do not, making audits and recounts problematic.

With all the vulnerabilities of machines, why not simply use paper ballots, and hand-count them, as some smaller districts do, or even some major democracies, such as Germany? The answer comes down to U.S. election structure, Stewart said. Americans vote on several candidates in each state, and in California and some other states, voters also weigh in on ballot measures. (California is particularly notorious for the sheer number of ballot initiatives to vote on; there are 17 this election day, including a proposition related to marijuana legalization.) Stewart noted that in Germany, voters have two votes: They choose a candidate from one list (representing them locally) and then a party from a second list. "Can you imagine a California ballot in Germany?" he said.

So to an extent, Americans are stuck coming up with a way to accurately count votes and still provide an audit trail.

Of course, one could go to paper-based systems and hand-counting, but it would take a lot longer to count the votes. That might not be a bad thing, Stewart said.

"I mean, why do we have to know right this minute?" Stewart said. "The president isn't even inaugurated until January. An extra day wouldn't make any difference."

Original article on Live Science.