Fearsome Malagasy Dinosaur Remained a Pipsqueak Most of Its Life

A fearsome carnivorous dinosaur known for eating its own kind wasn't that large — it weighed only about as much as a hefty crocodile. But the creature, Majungasaurus crenatissimus, took more than 20 years to reach its full size, making it one of the slowest growing dinosaurs of its kind on record, a new study finds.

The finding suggests that M. crenatissimus was a real pipsqueak for most of its life, at least compared with its fast-growing, enormous relatives Tyrannosaurus rex and Albertosaurus, said study lead researcher Michael D'Emic, an assistant professor of biology at Adelphi University in Long Island, New York. [Image Gallery: Tiny-Armed Dinosaurs]

Malagasy dinosaur

The researchers chose to study M. crenatissimus because it was a common dinosaur with multiple specimens available for study. "It's literally known from thousands of teeth, hundreds of isolated bones and several nearly complete skeletons," D'Emic told Live Science.

M. crenatissimus was top predator on the island of Madagascar during the late Cretaceous period, about 70 million to 66 million years ago. M. crenatissimus is considered an abelisaurid theropod — a bipedal, carnivorous dinosaur with stubby front arms; small, pointy teeth; and a short skull, D'Emic said.

When full-grown, the beast would have extended about 20 feet (6 meters) in length, according to a 2007 study in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

But it took most of its life to reach that length, D'Emic found. The individual the researchers studied likely weighed about 1,875 lbs. (850 kilograms) when it died at about age 27. In comparison, "T. rex was at 800 kilograms in just a few years," before it eventually reached its full size of about 9 tons (8,160 kg) in adulthood, D'Emic said.

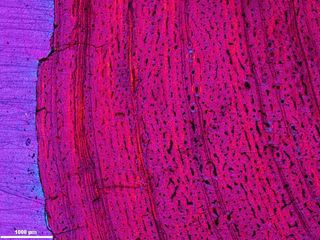

Rock-saw slice

To analyze the M. crenatissimus individual, one of the largest and most complete on record, the researchers used a rock saw to get slices from eight bones: the dorsal rib, pubis, scapula, phalanx, metatarsal and three leg bones — the fibula, tibia and femur.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To preserve the original shape of the skeleton, they used a mold to form an epoxy in the shape of the slices removed from those bones. Then they placed the replicas back into the skeleton.

"Although it's destructive sampling, you can restore the specimen to its original morphology," D'Emic said.

Once they had the eight slices, D'Emic and his colleagues mounted them on microscope slides and then ground them down until they were transparent (about the thickness of a human hair) and. "It's a slow, time-consuming process," he said.

Once he was done, D'Emic was able to easily view each individual line of arrest growth (LAG). Just like tree rings, LAGs that were close together indicated that the dinosaur didn't grow much that particular year, while rings that were far apart implied that the dinosaur had undergone a growth spurt, D'Emic said.

Many of the LAGs were close together, indicating that the dinosaur grew slowly in comparison to its theropod relatives. For example, the allosauroid Acrocanthosaurus reached about 7,700 lbs. (3,500 kg) in about the same time it took M. crenatissimus to reachjust a quarter of that weight, D'Emic said.

It's unclear why M. crenatissimus grew so slowly, but perhaps the harsh Malagasy environment, plagued by droughts and floods, curtailed its growth, D'Emic said. In addition, research shows that other abelisaurids grew slowly, so it may be a common characteristic of the group, he said. [Gory Guts: Photos of a T. Rex Autopsy]

Childhood mystery

However, some information is missing from the dinosaur's youth. Some bones, such as the tibia, contained bone marrow in their center that remodeled the bone (and the LAGs) around them, meaning that the dinosaur's early years were effectively erased.

But, by examining the spacing of the later years, they were able to guess how many rings made up the inner region covered by bone marrow. In the end, they guessed that there were 14, which helped them estimate the dinosaur's age of 27, he said. The researchers plan to study a juvenile M. crenatissimus to see whether its young LAGs are spaced as they predicted they would be, D'Emic said.

The research is part of the Madagascar Paleontology Project, in which researchers are studying bone structure and LAGs of other vertebrates that lived in Madagascar's Maevarano Formation, widely known as a stressful Cretaceous ecosystem, said study co-researcher Kristina Curry Rogers, an associate professor of geology and biology at Macalester College in Minnesota.

For instance, earlier this year, Curry Rogers, D'Emic and their colleagues published a study in the journal Science on the remains of a baby titanosaur (Rapetosaurus), a long-necked and long-tailed herbivore from Madagascar. They found that the baby likely died of starvation during a drought. But during its short life, it grew very fast, likely at the same rate as a modern baby elephant, she said.

The new study, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Oct. 28 at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.