In Photos: The Mummy of Queen Nefertari of Egypt

Mark of a King

A pommel marked with the name Khepar-Kheperu-Ra, the throne name of King Ay, who ruled Egypt for a few years right after the reign of King Tutankhamen, during the 18th Dynasty. This artifact was found, rather mysteriously, in the lavish tomb of Queen Nefertari, one of the royal wives of Ramesses II, or Ramesses the Great, who ruled from about 1279 B.C. to 1213 B.C. The discovery of this pommel in Nefertari's tomb may be a hint that she was related to these King Ay (and Tutankhamen), but firm proof of her ancestry is elusive. [Read more about Queen Nefertari's Burial]

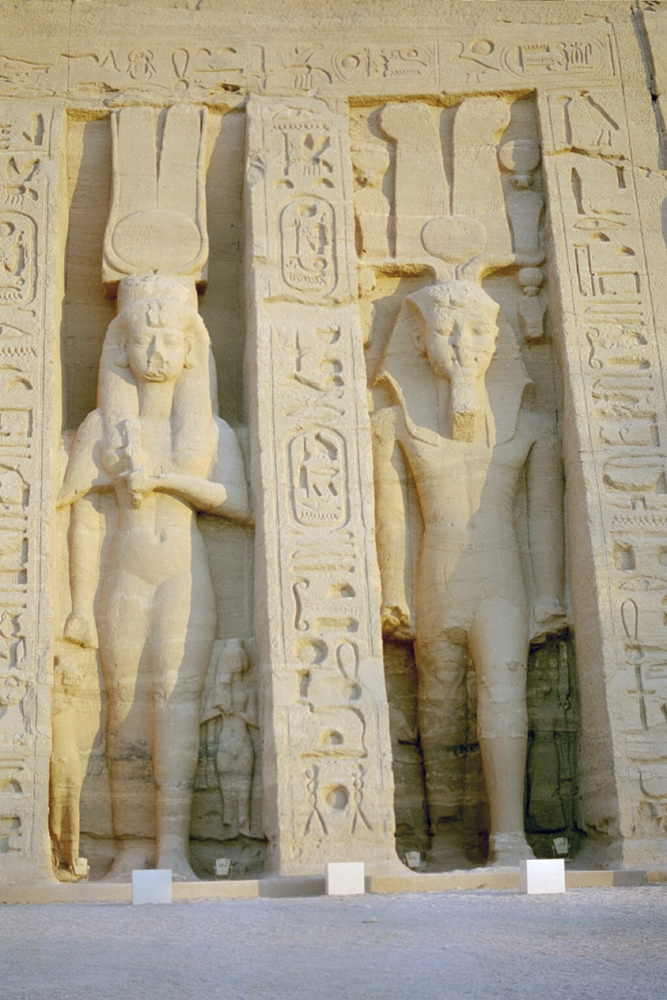

Important Queen

A statue of Queen Nefertari (left) at the rock temple Abu Simbel, dedicated in her honor. Her statue is the same size as her husband's (right), indicating her elevated status. Nefertari would eventually be entombed in one of the most elaborate tombs in the Valley of the Queens. Officially discovered in 1904 by modern Egyptologists, the tomb had been looted in antiquity. Nevertheless, it was decorated with colorfully painted plaster walls and contained fragments of the queen's pink granite sarcophagus, among other small artifacts.

Mysterious legs

Among the items found in QV 66 were two fragmentary, mummified legs, which are now held at the Museo Egizio Turin in Italy. The legs are in three pieces. One is a fragment of femur (thigh bone), patella (knee) and tibia (one of the bones of the lower leg). The other is another piece of tibia, and the third is a partial femur. As they were found in Nefertari's tomb, the legs were assumed to be hers, but no scientific analysis had ever proven that fact. [Read more about Queen Nefertari's Burial]

Long leg fragment

One of three leg fragments found in QV 66, the tomb of Nefertari, wife of Ramesses the Great. The wrapped fragment is just over 12 inches (30 centimeters) long. It consists of part of a thigh bone, the knee joint and part of one of the bones of the lower leg (the tibia).

Medium-sized leg fragment

The second-longest leg fragment from tomb QV 66 is part of a tibia. Also found in the tomb were sandals, coffer lids, pottery pieces, fabric scraps and 34 wooden shabtis, small figurines meant to provide the deceased manual labor in the afterlife. Many of the objects were inscribed with Nefertari's name.

Part of a thigh

The third piece of human remains found in QV 66 in the Valley of the Queens was this short portion of femur, or thigh bone. An attempt to analyze DNA from these mummified remains failed because of age and contamination in the sample, researchers wrote in the journal PLOS ONE.

[Read more about Queen Nefertari's Burial]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An ancient x-ray

An X-ray of the mummified leg fragments revealed extensive fracturing, most likely postmortem. The legs appear to belong to an adult female who was probably between 40 and 60 when she died, which is consistent with what is known of Nefertari's history, researchers wrote in the journal PLOS ONE. She is last "sighted" in reliefs showing her at a temple opening in the 24th year of Ramesses the Great's reign and is missing in reliefs from a festival in the king's 30th year of rule. That would put her at around 40 to 50 when she died.

Arthritic knees?

On the left, an arrow marks signs of possible arthritis on the bones found in QV 66. On the right, an arrow points to possible calcification in the arteries that runs alongside the tibia. Both arthritis and arterial calcification are signs of age, and possibly indicate minimal physical labor. [Read more about Queen Nefertari's Burial]

Thigh x-ray

An X-ray of the portion of right femur, or thigh bone, ensconced in mummy wrappings. Analysis of the leg bones suggest that they belonged to a middle-age or elderly woman who stood between 5 feet 5 inches and 5 feet 7 inches (165 to 168 centimeters). This interpretation was bolstered by a forensic analysis of the sandals in the tomb, which would have fit someone standing around 5 feet 5 inches.

Calcification

A hint of a modern disease in an ancient mummy: The QV 66 remains show calcifications in the anterior and posterior arteriae tibiales, the arteries that run down the lower leg. This could be a sign of arteriosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries, or medial calcific sclerosis, an age-related hardening of the vessels, researchers reported.

Royal Sandals

Sandals found in tomb QV 66 would have fit someone about 5 feet 5 inches (165 centimeters) tall, according to forensic analysis. This method is not necessarily exact, but matches the height extrapolated from the leg bones found in the tomb. The sandals in the tomb would have fit between a European size 39 and 40, or around a size 6.5 and 7 in the United States. The connection between the sandals and the remains as well as radiocarbon dating and chemical analysis suggest that the mummified fragments do indeed belong to Queen Nefertari, the researchers concluded. [Read more about Queen Nefertari's Burial]

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.