Bipedal Human Ancestor 'Lucy' Was a Tree Climber, Too

"Lucy," an early human ancestor that lived 3 million years ago, walked on two legs. But while she had her feet firmly planted on the ground, her arms were reaching for the trees, a new study shows.

High-resolution computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans of long bones in Lucy's arms reveal internal structures suggesting that her upper limbs were built for heavy load bearing — much like chimpanzees' arms, which they use to pull themselves up tree trunks and to swing between branches.

This adds to a growing body of evidence that although Lucy's pelvis, leg bones and feet supported bipedal walking, her upper body was adapted for at least partial life in trees — far more so than in modern humans. [Human Ancestor 'Lucy' Was A Tree-Climber, Bone Scans Reveal | Video]

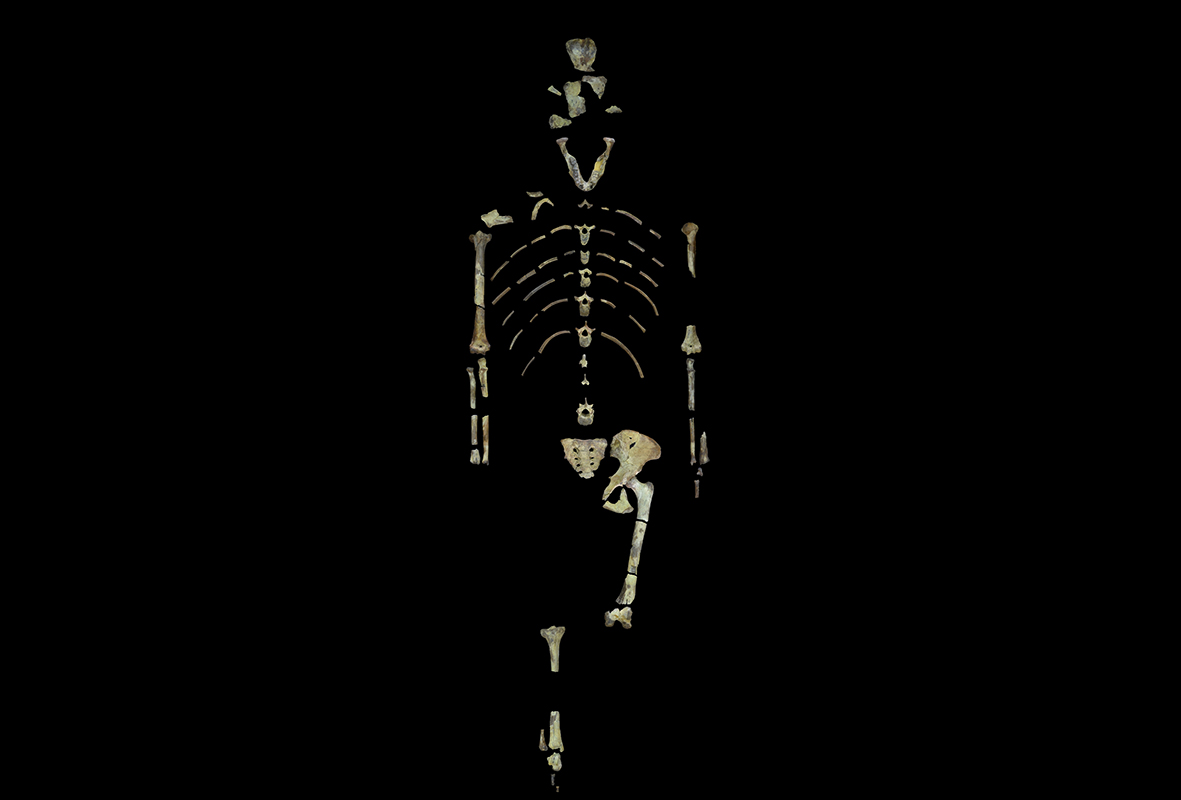

Lucy was discovered in 1974 in Ethiopia, and for decades she represented the only known skeleton of the hominid species Australopithecus afarensis. Scientists knew from other fossil finds that females of the species were smaller than males, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and the size of Lucy's skeleton indicated that she was female.

While her skeleton was only 40 percent complete, it included long bones from her arms (humerus) and legs (femur), a partial shoulder blade and part of her pelvis, which helped scientists determine she was bipedal.

But scientists have argued that anatomical features also suggest that Lucy was partly arboreal — a tree dweller.

The researchers delved into a digital archive of more than 35,000 CT "slices" — single images of bone cross-sections — to peer inside Lucy's left and right humerus and her left femur, to see what they might reveal about her tree-climbing habits. They then compared the internal structures to bones from other fossil hominids, chimpanzees and modern humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Load-bearing arms

The study is grounded in mechanical engineering principles, lead author Christopher Ruff, a professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said in a statement.

He explained that bones required to support a lot of heavy lifting are bulkier in order to bear the extra strain. Other studies have even shown that bones can bulk up over time in response to high-stress demands, according to study co-author John Kappelman, a paleoanthropologist with the University of Texas at Austin.

"It is a well-established fact that the skeleton responds to loads during life, adding bone to resist high forces and subtracting bone when forces are reduced," Kappelman said in the statement. "Tennis players are a nice example: Studies have shown that the cortical bone in the shaft of the racquet arm is more heavily built up than that in the non-racquet arm," he added.

Structural proportions in Lucy's bones told the scientists that she was far more adapted for climbing than modern humans. And like chimpanzees, she likely spent a good portion of time in trees, perhaps to escape from predators or to find food.

An ape-like shoulder

Before this study, there was some debate among scientists about how Lucy may have divided her time between the ground and the trees, according to Will Harcourt-Smith, an associate professor of anthropology at Lehman College in the City University of New York, and a research associate in the vertebrate paleontology department at the American Museum of Natural History.

"The argument about whether Lucy was a full committed biped was heavily challenged in the 1980s by a number of studies," Harcourt-Smith told Live Science. "When you look at the anatomy — an ape-like shoulder joint, aspects of the wrist, elbow and foot — there are all these features that indicate she was still climbing in trees a significant part of the time."

Lucy's shoulder joint, in particular, hinted that she was probably a tree climber, he added. "The orientation of the joint essentially indicates she would have had a range of motion more conducive to pulling herself up in the trees," Harcourt-Smith explained.

Another A. afarensis discovery in 2012 — a 3-year-old girl called "Selam" — offered additional evidence that this species was at least partly arboreal. Selam's shoulder blades were angled like apes', suggesting that her arms were adapted for active climbing, even at this early age. [Image Gallery: 3-Year-Old Human Ancestor Revealed]

"And then along comes this new study, looking at cross-sectional profiles of the long bone, and the stress and strain that would have gone through those bones," Harcourt-Smith said.

"I think it's a very strong biomechanical argument that they had these strong upper limbs that were outside the range of variations seen in humans, and were much more like an ape. So it's very complementary to that initial work on the shoulder bones," he added.

The findings were published online Wednesday (Nov. 30) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.