2016 'Arctic Report Card' Gives Grim Evaluation

It's been a crazy year in the Arctic, even for a region that has seen profound changes over the past few decades, changes that have been driven largely by manmade climate change. Sea ice has thinned and shrunk and the Greenland ice sheet has lost ice, fueling Arctic warming to reinforce itself, which has sent temperatures there rising twice as fast as the planet as a whole.

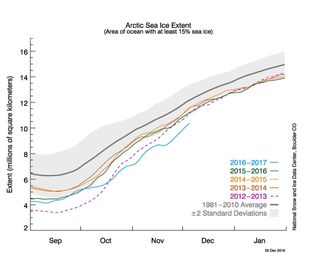

And 2016 amplified those trends. It set record lows for both the sea ice winter peak and summer minimum, and sea ice made a virtually unprecedented cold season retreat in mid-November.

Air temperatures also soared to record heights, and the Greenland Ice Sheet had the second earliest onset of the spring melt season on record, according to the annual Arctic Report Card released on Tuesday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

"We've seen a year in 2016 in the Arctic like we've never seen before," Jeremy Mathis, director of NOAA's Arctic research program, said during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The Arctic is a Seriously Weird Place Right Now Arctic Sea Ice Sees Strange Cold Season Retreat Here's How Much CO2 Will Make the Arctic Ice-Free

The year showed "a stronger, more pronounced signal of persistent warming than any other year in our observation record," he said.

These changes have had considerable impacts on Arctic ecosystems and native communities, as well as opening up the fragile region to more commercial activity. But they also have impacts outside the region, including potentially influencing weather conditions over North America, Europe and Asia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Skyrocketing Temperatures, Plummeting Sea Ice

The Arctic has continued to warm at twice the rate of the planet as a whole, and 2016 reinforced that trend. The annual average temperature (from October 2015 to September 2016) was 3.5° Fahrenheit (2°Celsius) above the 1981-2010 average, the highest in records that go back to 1900. Since that time, the Arctic has warmed 6.3° Fahrenheit (3.5° Celsius).

More localized temperatures skyrocketed even more, thanks to winds pulling in warmer air from the south. In January 2016, some places saw temperatures that were a stunning 14° Fahrenheit (8° Celsius) above average, according to the report, which has been issued every year since 2006. The 2016 edition was compiled by 61 scientists from 11 countries.

Those warm temperatures contributed to extremely low sea ice coverage, which has been on a downward spiral for several decades. The end-of-summer minimum is now half of what it was just three decades ago.

The warm weather that persisted throughout winter pushed sea ice extent to a record low at the end of winter, when sea ice reaches its annual peak, for the second year in row.

Cooler and cloudier summer weather helped dampen melt for much of the season, but the summer minimum still tied 2007 as the second-lowest on record. All 10 of the lowest sea ice extents on record have happened since 2005.

The decrease in area covered by sea ice means that there is less sunlight being reflected back by that sea ice and more being absorbed by dark, newly exposed ocean waters, driving the amplified warming in the Arctic. Sea surface temperatures in August 2016 were 9° Fahrenheit (5° Celsius) warmer than the long-term average in areas near Alaska, Russia and Greenland.

But the ice isn't just decreasing in area, it is also thinning, with a larger proportion of the ice cap made up of the youngest, thinnest ice. In March 2016, multi-year ice (or ice that has survived at least one melt season) made up only 22 percent of Arctic sea ice, compared to 45 percent in 1985.

'Really Fragile Sea Ice'

How this thin, more vulnerable ice is affected by the rapidly changing conditions of the Arctic was the subject of a rare and dangerous Arctic expedition, the results of which were also presented at the AGU meeting.

The project, called the Norwegian Young Sea ICE expedition, lodged a research ship into this young sea ice for six months during 2015, taking measurements of air, ice and ocean water.

What they found was that "this ice functions very differently than it did 10 years ago," Mats Granskog, a researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute and the expedition's chief scientist, said during a press conference. "It moves much faster; it breaks up more easily; it's much more vulnerable to storms and wind."

Several storms blew directly over the ship, including one that raised the air temperature from -40° Fahrenheit to 32° Fahrenheit in less than 48 hours. It also increased the moisture in the air by a factor of 10 and took winds from calm to more than 50 mph.

Those strong winds could easily push around the ice and break it up. The movement of the ice also stirs up the ocean, pulling up warmer waters from below and contributing to ice melt, particularly in the summer, the scientists found.

On one June day, the researchers watched the sea ice disintegrate under one of their camps. The camp was located on a miles-long stretch of ice several feet thick, but beginning early one morning, it broke up over a matter of hours, sending the researchers scrambling to save their equipment and its valuable data.

"So really what we saw out there was really fragile sea ice," said expedition member Amelie Meyer, also of the NPI.

That fragile sea ice affects Arctic life, for example, triggering earlier blooms of tiny phytoplankton below the ice, which the team observed. Changing ocean conditions also affect Arctic fisheries, which are crucial to the livelihoods of native communities. Less sea ice also puts those coastal communities under threat from punishing winter storm waves.

The opening of the Arctic has also increased commercial interest there, including shipping and oil and mineral exploration, which puts an already threatened region under more stress, Meyer said.

Arctic 'Shouting Change'

The stunning changes to sea ice continued this year with "a record-breaking delay of fall freeze-up," Dartmouth's Donald Perovich, lead author of the sea ice section of the 2016 report card said. The fall even featured a virtually unprecedented retreat in sea ice for a brief period in mid-November, something that could happen more often as the Arctic continues to warm.

One proposed way that these declines in sea ice may have impacts beyond the Arctic is the idea that they could be impacting heat energy reaching the atmosphere and affecting weather patterns over the continents of the northern hemisphere, including the U.S. But this theory is contentious and many atmospheric scientists are not yet convinced.

Changes in the Arctic aren't limited to sea ice, though. Spring snow cover in the North American sector was the lowest on record, going back to 1967.

The Greenland Ice Sheet "continued to lose mass in 2016 as it's done since 2002" when satellite records of that measure began, said Marco Tedesco, lead author of Greenland chapter of the report and a researcher with Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The massive ice sheet, which is contributing to rising global sea levels, had the second earliest start to a melt season on record, with that season lasting up to 40 days longer than average in some regions.

"The impacts of the persistent warming trend over the last 30 years in the arctic are clearly evident" in both land and ocean, Mathis said.

With questions looming about how the incoming Trump administration might change the landscape of climate research, Mathis said that he didn't envision any changes to the Arctic Report Card.

"We will continue to do that regardless of what happens going forward," he said.

Such research is ever more important as the changes in the Arctic continue to snowball. As Perovich, of Dartmouth, put it, the Arctic was whispering change just a couple decades ago, but "now it's not whispering anymore — it's speaking change; it's shouting change."

You May Also Like: Rick Perry Tapped to Run Energy Agency He Vowed to Kill Trump Picks Exxon's Rex Tillerson for Secretary of State Fossil Fuel Divestments Now Represent $5.2 Trillion Trump Reportedly Tabs Another Climate Denier, This Time for Interior

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.