Tiny Starfish Larva Mesmerizes in Award-Winning Video

A time-lapse video showing the hypnotic flow of water swirling around a minuscule starfish larva earned first place in the 2016 Nikon Small World in Motion Photomicrography Competition.

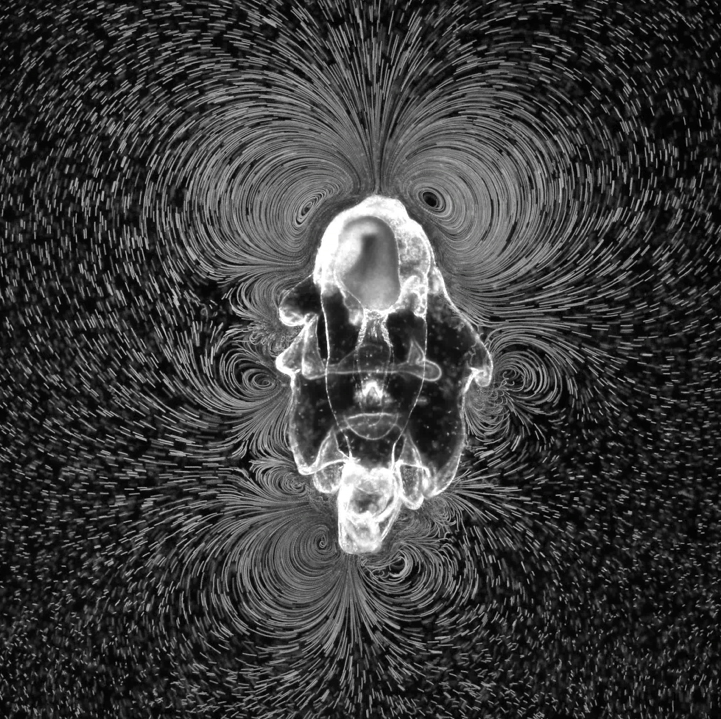

Captured against a black background, tiny illuminated plastic particles in the water swirl around the larva's body, revealing the complex movement of currents that the larva generated with its cilia — hair-like structures — to carry food closer. The starfish larva measured 1 millimeter in length and was photographed by William Gilpin, a doctoral candidate in applied physics at Stanford University.

The contest, now in its sixth year, honors exceptional videos that celebrate the wonder and beauty of life at the microscopic level, showcasing animal movement and biological activity too small to be seen with the naked eye. [Tiny Predators Win Video Microscopy Contest | Video]

This year, Nikon chose three top videos and 17 honorable mentions — these included the magnified head of a faucet snail, crystal growth, blood circulating in a tadpole's tail, and cell division in green algae. The company announced the winning submissions on their website today (Dec. 14).

Surprising behavior

Not only is the prizewinning video mesmerizing to look at, it revealed behavior that was previously unknown in starfish larvae.

The larva used its cilia to whip the water around it into vortices that acted like tiny conveyer belts for nearby food — but this convenience comes at a cost. By agitating the water, the larva could signal its location to predators as easily as it stirs up food, and expending all that energy inhibits its ability to escape if threatened, the scientists found.

Capturing the larva's stirring performance on video offered a double opportunity to the researchers: to study the unusual behavior more closely and to distribute it more widely, Gilpin said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It gives us a chance to share and explain scientific discoveries that we hope will appeal to many other scientists, as well as the public at large," he said.

"It's incredible and exciting that something as widely known as a starfish can exhibit an unexpected and beautiful behavior, and we hope to share our excitement with others," Gilpin added.

Winner by a neck

The second-place video won by a neck — the extended "neck" of a predatory protozoan, a single-celled organism called Lacrymaria olor, which translates as "swan's tear." In the video, the protozoan searches for single-celled prey by repeatedly stretching its neck, extending it up to seven times the length of its body.

Third place went to a time-lapse video showing the rapid expansion of a type of mold — and it's far more beautiful than you might expect. Aspergillus niger grows on fruit, and in the video it blooms in puffy, colorful "blossoms" that almost resemble flowers. It was captured in action by photographer Wim van Egmond, who said in a statement that he firmly believes that microscopy is for everyone, and that contests like this one are a great way to introduce people to worlds that are waiting to be discovered, if only one is willing to look closely enough.

"The result of the selection of footage from many contributors is a kaleidoscopic overview of what microscopy is all about," van Egmond said. "And you don't have to be a professional to enjoy micro life."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.