Polar Vortex: The Chilly Science of an Arctic Blast

In the past few years, a new term has entered the everyday lexicon: Polar vortex.

Sounds scary — and it's true, you'll want to bundle up if the polar vortex is about to affect your local weather. But it's a bit unfortunate that the polar vortex has become associated with frigid temperatures in the United States, meteorologists say. In fact, the maligned circulatory pattern is usually responsible for keeping cold air locked at the North Pole.

Usually.

Then there are those times when the polar vortex stretches its wings and sends Arctic air southward. It's not that the polar vortex goes wandering, said Jason Furtado, a meteorologist at the University of Oklahoma.

"The polar vortex is still there, spinning over the polar regions," Furtado said. "It's just the edges of it that get deformed, and you get these cold-air outbreaks that can come down."

What the polar vortex is

The polar vortex is part of a low-pressure system, and just like other lows this one spins as winds blow in toward the lower pressure at the center of the system. (A hurricane is another example of a low-pressure system that spins.) Due to Earth's spin and a phenomenon called the Coriolis effect, these systems spin counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

As the North Pole tilts away from the sun in the winter months, bathing it in 24 hours of darkness, temperature gradients form between higher and lower latitudes, Furtado said. These gradients drive winds, leading to a pattern of low pressure that circulates counterclockwise around the pole.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The polar vortex is technically in the stratosphere, the middle layer of Earth's atmosphere. That area of low pressure is about 20 miles (32 kilometers) above the Earth's surface, Furtado said. The vortex affects daily weather when it drops down into the troposphere, the lowest layer of the atmosphere. [Earth's Atmosphere: Top to Bottom (Infographic)]

Does the South Pole have a vortex?

There are polar vortexes at both the North and South Poles, with the Southern Hemisphere vortex spinning clockwise. In each case, the vortex strengthens during winter and weakens during summer. The vortex at the South Pole is more stable than the one at the North Pole, said Brian Jackson of the National Weather Service, because there are fewer land masses in the Southern Hemisphere.

"It's a more stable environment, so it's less likely to be broken down as often as the Arctic," Jackson said.

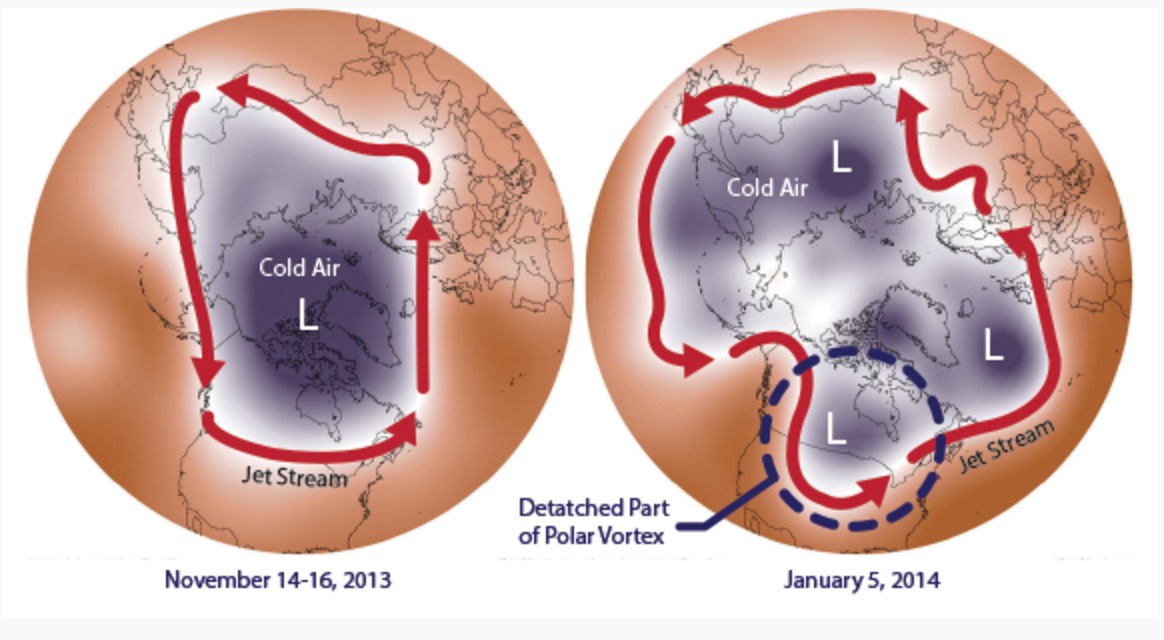

In the Arctic, when some atmospheric event interferes with this spinning air, the United States and other areas to the south may see temperatures plunge. "It's a little rare for it to come so far south that we start to see it in the U.S., but every once in a while, we get a storm system that will start to disturb it," Jackson said.

"The polar vortex itself is actually stronger during the winter, but can be disrupted by fluctuations in the atmosphere that created these events, such as strong storm systems that pull warmer air into the Arctic and force the colder air out," Jackson told Live Science.

What the polar vortex does

Usually, there's a barrier keeping that Arctic air at the North Pole — the jet stream, a river of strong winds that often travels west to east across the U.S., following boundaries between cold and hot air.

"The jet stream is the barrier between the cold, arctic air to the north, and more temperate air to the south," Jackson said. "When the jet stream surges southward in these [polar vortex] events, it allows cold Arctic air to spill in behind it."

When a storm churns the polar vortex and disrupts its smooth circulatory pattern, the shape of the vortex can stretch. Lobes form that can spill cold air southward, as is happening in the Midwest and as is forecasted to happen in the northeastern United States into the weekend. Jackson said that it's sort of like an underfilled water balloon: When you squeeze it in one place, the water balloon pops out someplace else.

Meteorologists have known about the polar vortex for more than 100 years, but the term became popularized in 2014, when back-to-back intrusions by lobes of the vortex chilled Americans in January and February. The country has also seen large polar vortex intrusions in 1977, 1982 and 1989, Jackson said.

As the Arctic air moves southward, it warms — and back at the pole, as the disturbance that weakened the vortex's flow ends, the circulatory pattern strengthens. This locks cold air back at the pole and brings relief to those shivering at lower latitudes.

How long will Arctic blast last?

You may not have to stay too bundled up for long, as meteorologists expect this blast of Arctic air to go back home soon.

"We're expecting a second lobe of this [polar vortex] event to move through early next week and start to head out by late Monday/Tuesday [Dec. 19–20]," Jackson said. "Following that, more typical patterns of temperature variations are expected to resume. In fact, after this week, patterns favor warmer-than-normal conditions for the eastern half of the country."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.