Who Invented the Traffic Light?

Traffic lights, or traffic signals, are located on most major corners in cities and towns around the world. The red, yellow and green lights let us know when it is safe to drive through the intersection and when to walk across the street as well as when to stop and let other drivers, bikers and pedestrians take their turns to continue on their way.

The first traffic signal

Traffic jams were a problem even before the invention of the automobile. Horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians crowded the roads of London in the 1860s, according to the BBC. A British railway manager, John Peake Knight, suggested adapting a railroad method for controlling traffic.

Railroads used a semaphore system with small arms extending from a pole to indicate whether a train could pass or not. In Knight's adaptation, semaphores would signal "stop" and "go" during the day, and at night red and green lights would be used. Gas lamps would illuminate the sign at night. A police officer would be stationed next to the signals to operate them.

The world's first traffic signal was installed on Dec. 9, 1868, at the intersection of Bridge Street and Great George Street in the London borough of Westminster, near the Houses of Parliament and the Westminster Bridge, according to the BBC. It was a success and Knight predicted more would be installed.

However, only one month later, a police officer controlling the signal was badly injured when a leak in a gas main caused one of the lights to explode in his face. The project was declared a public health hazard and immediately dropped.

Competing patents

Following the accident, about four decades passed before traffic signals began to grow in popularity again, mainly in the United States as more automobiles hit the road. The early 1900s saw several patents being filed, each with a different innovation to the basic idea.

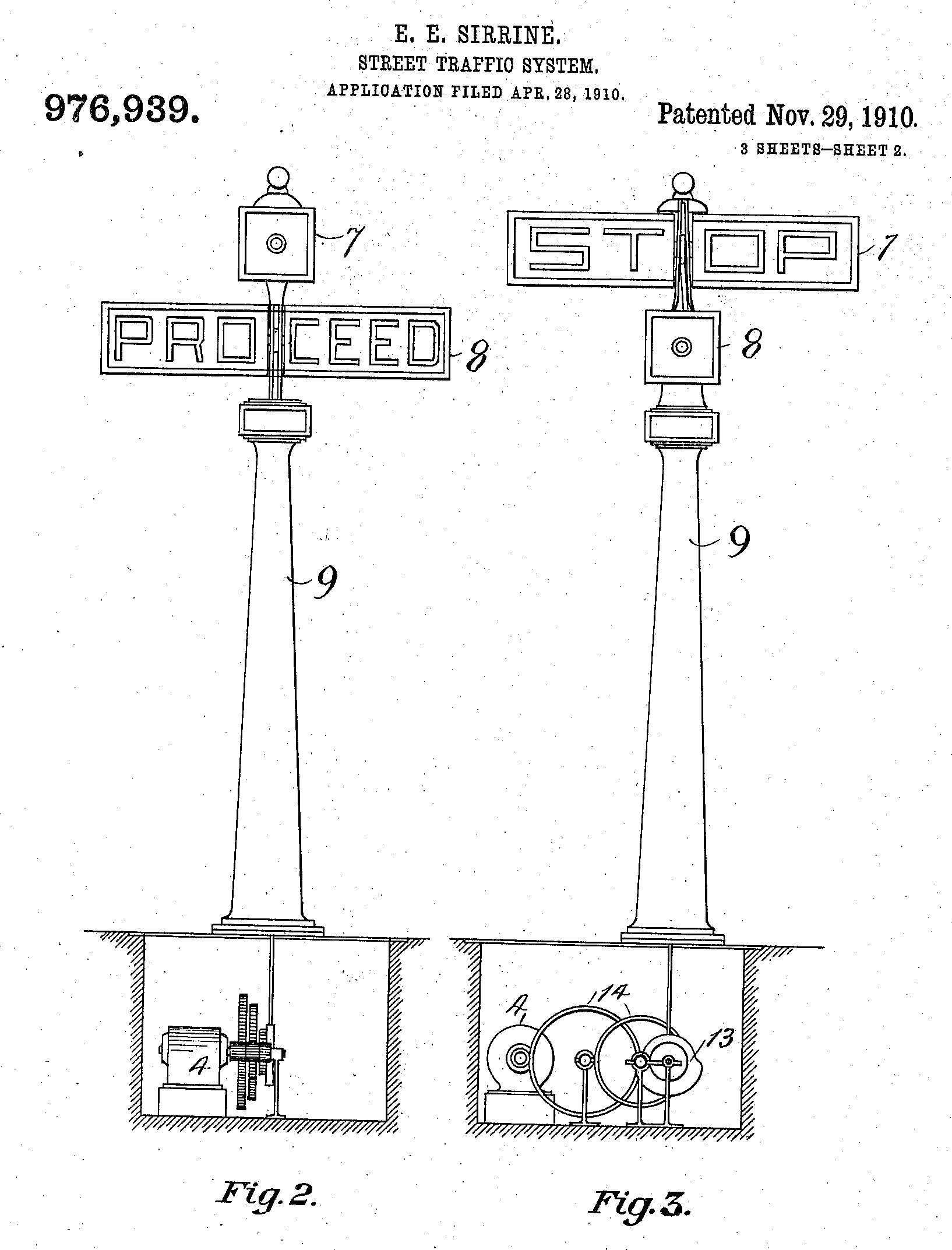

In 1910, Ernest Sirrine, an American inventor, introduced an automatically controlled traffic signal in Chicago. His traffic signal used two non-illuminated display arms arranged as a cross that rotated on an axis, according to Inventor Spot. The signs said "stop" and "proceed."

The first electric traffic light using red and green lights was invented in 1912 by Lester Farnsworth Wire, a police officer in Salt Lake City, Utah, according to Family Search. Wire's traffic signal resembled a four-sided bird-house mounted on a tall pole. It was placed in the middle of an intersection and was powered by overhead trolley wires. A police officer had to manually switch the direction of the lights.

However, the credit for the "first electric traffic signal" usually goes to James Hoge. A system based on his design was installed on Aug. 5, 1914, in Cleveland. Hoge received a patent for the system in 1918. (He had filed his application in 1913.) Hoge's traffic signal used the alternating illuminated words "stop" and "move" installed on a single post on each of the four corners of an intersection. The system was wired such that police and fire departments could adjust the rhythm of the lights in case of an emergency.

William Ghiglieri of San Francisco patented the first automatic traffic signal that used red and green lights in 1917. Ghiglieri's design had the option of being either automatic or manual.

Then in 1920, William Potts, a Detroit police officer, developed several automatic traffic light systems, including the first three-color signal, which added a yellow "caution" light.

In 1923, Garrett Morgan patented an electric automatic traffic signal. Morgan was the first African-American to own a car in Cleveland. He also invented the gas mask. Morgan's design used a T-shaped pole unit with three positions. Besides "Stop" and "Go," the system also first stopped traffic in all directions to give drivers time to stop or get through the intersection. Another benefit of Morgan's design was that it could be produced inexpensively, thus increasing the number of signals that could be installed. Morgan sold the rights to his traffic signal to General Electric for $40,000.

The first electric traffic light in Europe was installed in 1924 at Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, according to Marcus Welz, CEO of Siemens ITS (Intelligent Traffic Systems) US. The five-sided traffic light was mounted on a tower and was primarily manual with some automation, which only required a single police officer to manage. A replica now stands nearby and is a popular tourist attraction.

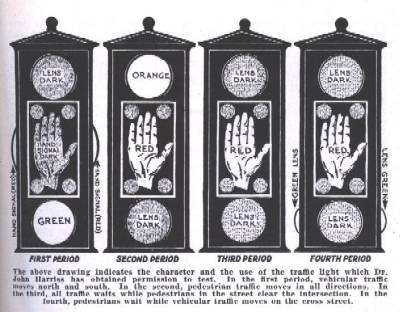

Pedestrian signals began to be included on traffic signals in the 1930s, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation. A "Walk/Don't Walk" signal was first tested in New York in 1934. It even used an upright palm to indicate "Stop."

John S. Allen, an American inventor, filed one of the earliest patents in 1947 for a dedicated pedestrian traffic signal. Allen's design had the pedestrian signal mounted at curb level. Allen also proposed that the signals could contain advertisements. In his application, he explained that the words "Stop" and "Go" could be followed by the word "for," which in turn would be followed by a brand name.

Improving safety and efficiency

Traffic signals continue to improve. Many traffic signals are "intelligent" and can monitor real-time traffic situations, including direction, volume and density, as well as prioritizing public transportation systems, according to Welz.

For example, Welz said, Siemens is working on a project in Tampa, Florida, to implement Connected Vehicle Technology. This system allows the traffic light system to communicate directly with the car and will improve safety and efficiency. Communications are sent from over 40 traffic lights to cars equipped with the technology to receive the basic safety messages either on the rearview mirror or in-dash computer screen.

Simple messages are sent to the cars using both pre-existing and newly installed technologies that allow a driver to receive information such as the state of the upcoming traffic lights and recommendations on speed to get through both a particular intersection as well as the next handful of traffic lights. This project has shown great increases in efficiency in how traffic moves through intersections, Welz said.

The future of traffic lights

With self-driving cars becoming more of a reality, many improvements to traffic signals are considering the new and upcoming technologies. Researchers at the MIT Senseable City Lab published a scenario, in 2016 in PLoS ONE, where traffic signals are essentially nonexistent. In this potential future, all autonomous cars are in communication with each other in what is known as a "slot-based" intersection in which cars, instead of stopping, automatically adjust their speed to pass through the intersection while maintaining safe distances for other vehicles. This system is flexible and can also be designed to take pedestrians and bicyclists into account.

Another innovation called Surtrac is coming out of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, from a company called Rapid Flow Technologies. Pilot tests have been underway since 2012. The traffic signals use artificial intelligence to adapt to changing traffic conditions. The company says travel times have been reduced by more than 25 percent and wait times at red lights down an average of about 40 percent decreasing emissions. The system takes into account second-by-second real-time conditions and is scalable to larger areas since each intersection makes its own decisions instead of a single, central system.

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachel Ross is a science writer and editor focusing on astronomy, Earth science, physical science and math. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the University of California Davis and a Master's degree in astronomy from James Cook University. She also has a certificate in science writing from Stanford University. Prior to becoming a science writer, Rachel worked at the Las Cumbres Observatory in California, where she specialized in education and outreach, supplemented with science research and telescope operations. While studying for her undergraduate degree, Rachel also taught an introduction to astronomy lab and worked with a research astronomer.