Winter Outlook 2017: What's the Forecast for Your Region?

Is the United States in for a bitterly cold winter or a bearable one? It all depends on where you live, according to a three-month outlook released Thursday (Dec. 15) by the U.S. Climate Prediction Center (CPC).

Because of the cooling effects of the weather pattern called La Niña and other factors, temperatures and rainfall won't be par for the course across large swaths of the country this year, said Jon Gottschalck, a meteorologist with the CPC.

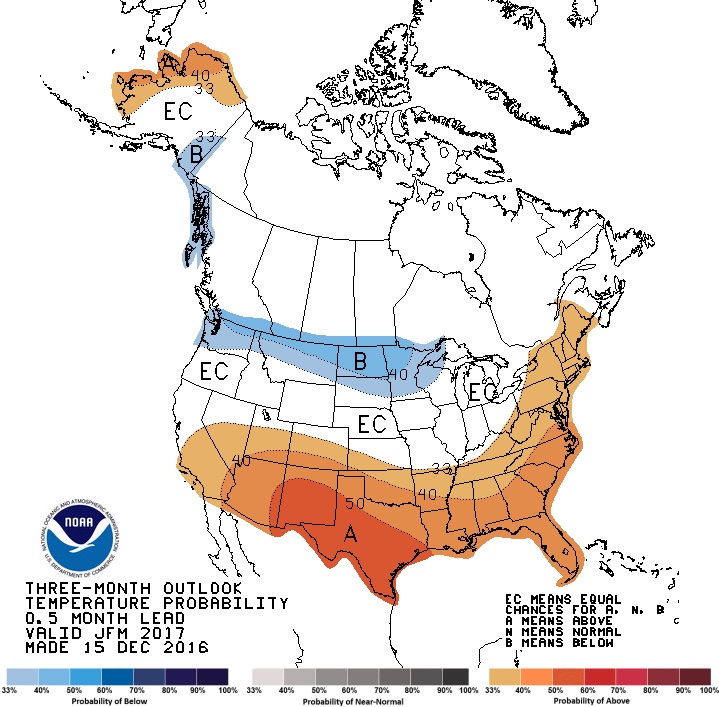

"Right now, the latest outlook for January, February and March is, we're favoring below-normal temperatures for an area in the northern tier of the U.S. — from the Pacific Northwest to the western Great Lakes, and also for the Alaska Panhandle and parts of extreme southeast Alaska," Gottschalck told Live Science. [Photos: The 8 Coldest Places on Earth]

In part, that's because during the La Niña weather pattern, "there tends to be what we call more high pressure in the atmosphere in the North Pacific," Gottschalck said. "That tends to build atmospheric blocking events."

These blocking events disrupt the west-to-east flow of air in the atmosphere, and can lead to wavy patterns in the fast-flowing jet stream, sending cold air into the interior of the United States. "This year, we're expecting a little bit more in the way of a wavy jet stream, on average," Gottschalck said. "For example, the cold air we're experiencing now across much of the country is related to one of these blocking type events."

In contrast, the three-month outlook predicts above-average temperatures along the East Coast and across the southern part of the country, with the best odds for warm weather in the southern parts of New Mexico and Texas, according to the CPC report. Moreover, above-average temperatures are also expected for western and northern Alaska.

But these unusual changes won't stay for long; this year's La Niña is expected to remain fairly weak and be short-lived, Gottschalck said. La Niña happens when the ocean surface temperatures around the equator are cooler than usual. But as it peters out later this winter, and "especially into the spring, we'll start to see more neutral conditions, meaning the ocean temperatures in the equatorial and central Pacific will become closer to average than what we currently have," Gottschalck said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rainy in many areas

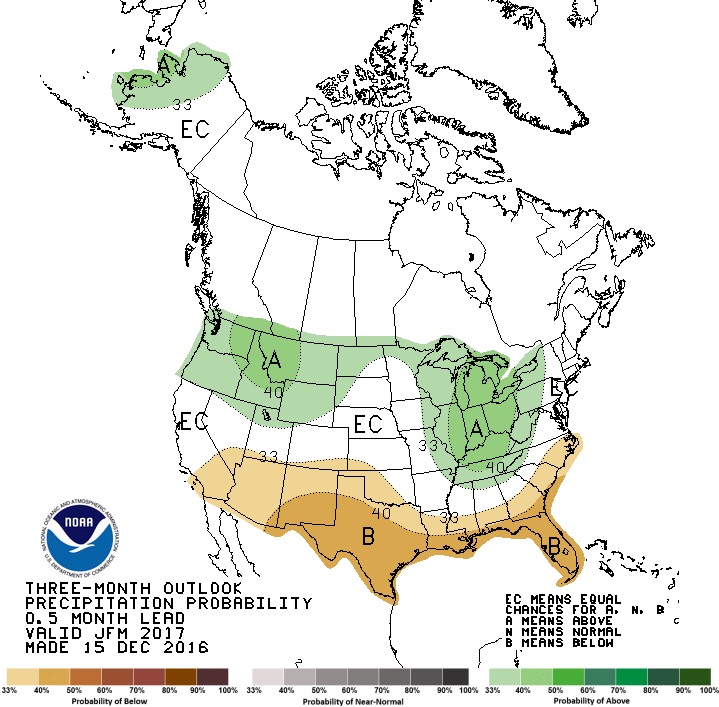

People in several regions of the country should expect to see unusually high amounts of rainfall this winter. In the Pacific Northwest, the northern area of the Great Basin, the Rockies and the High Plains, the CPC expects an above-average rainfall, the report said.

There's also an increased chance of above-average rainfall for the region around the Great Lakes, including Ohio, as well as the Tennessee Valley. The northwest part of Alaska is also expected to get more rain than usual, the report said.

But not all states will be soaked. Southern California, the Southwest, the southern Great Plains, the Gulf Coast, Florida and the southern Atlantic coastal areas are expected to receive less rainfall than usual, the CPC said.

The CPC, which is a part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), doesn't make long-term snowfall predictions (those can be made only a few days in advance), but Gottschalck did offer a possible forecast. [The 10 Worst Blizzards in US History]

"During La Niñas, the storm tracks tend to shift a little bit, so there tends to be more snowfall across parts of the New England area, and there tends to be less snowfall over parts of the mid-Atlantic," he said, adding that some areas of the Pacific Northwest and interior West may see more snow than usual. But it's really too soon to say at this point, he said.

The drought

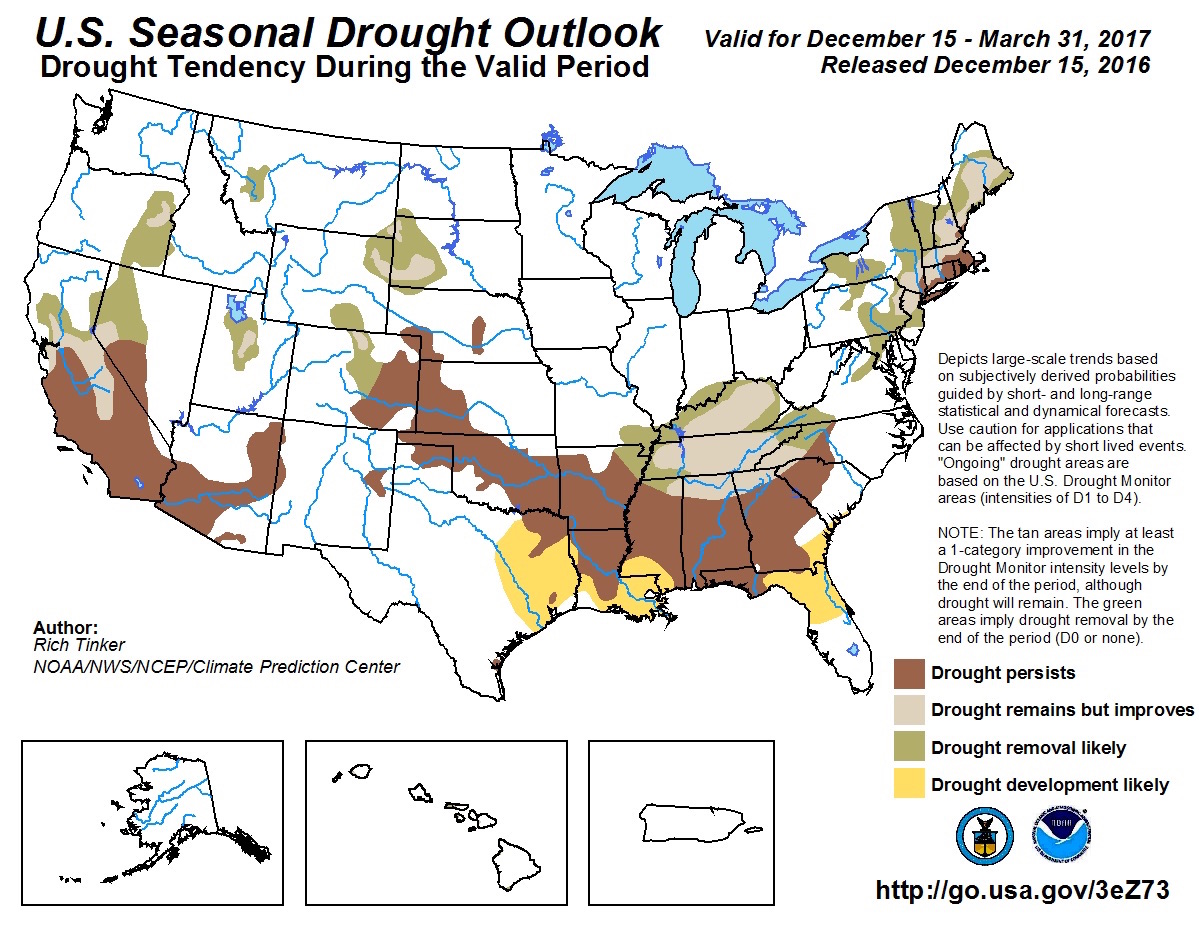

The drought may lessen in some regions, but not for the areas that need rainfall the most, according to the three-month outlook. Conditions in regions that experienced drought earlier this year — including parts of Washington, Oregon and northern California — have improved, and these regions are no longer experiencing water shortages, Gottschalck said.

"The areas that are still under the gun with exceptional drought conditions are central California and parts of southern California," he said. Luckily, those regions are expected to get some rainfall from storms over the next few days, but that won't fix any long-term problems, because the "drought is much more entrenched [there]," Gottschalck said.

These winter 2017 predictions are based on information from satellites and weather models, as well as conditions between 1981 and 2010, according to the CPC report. Even so, "there's always uncertainty with climate forecasts," Gottschalck said. "They're not the same as weather forecasts; that's why they're given in a probabilistic sense."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.