'Nightmare' Superbug May Have Spread Outside Hospitals

Six people in Colorado recently became infected with a "nightmare" superbug that until now, has mostly been limited to people in hospitals, according to a new report. The new cases suggest the superbug may have spread outside of health care facilities.

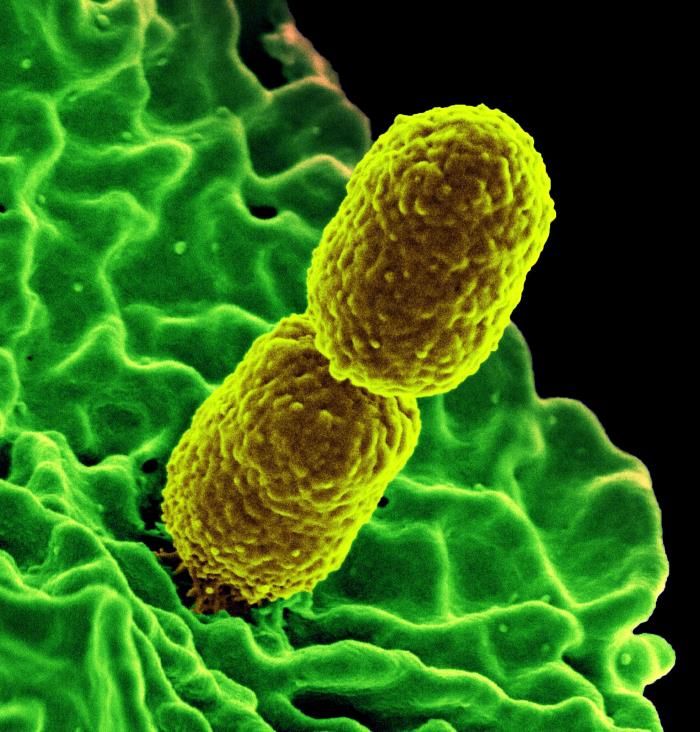

The superbug is known as carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE, a family of bacteria that are difficult to treat because they are resistant to powerful antibiotics. So far, nearly all cases of CRE infections have been seen in people who stay in health care facilities, or who have been treated with certain medical procedures or devices, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

But the six people in the new report had not stayed in a health care facility for at least a year before they contracted the infection. They had not recently undergone surgery or dialysis, either, and hadn't received any invasive devices, such as having a catheter or feeding tube inserted — all of which can be risk factors for CRE infections, the report said.

Thus, the six cases appear to be "community-associated" CRE infections, meaning the patients may have picked up these bacteria from somewhere in their everyday lives, outside of a health care setting.

CRE infections outside of a health care setting are "unusual for these bacteria," said study researcher Sarah Janelle, a health care-associated infections epidemiologist at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. These six cases suggest that "these bacteria might be moving from health care to community settings," Janelle told Live Science. "Further surveillance of CRE is needed to determine whether this pattern continues in Colorado and to determine if this trend is occurring in other parts of the United States," Janelle said. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

CRE have been dubbed "nightmare" bacteria because they are resistant to nearly all antibiotics, and they can be highly lethal, killing up to 50 percent of infected patients, according to the CDC.

The type of bacteria that cause CRE infections can be found in human guts, where the bugs are usually harmless. But infections can arise if the bacteria enter another part of the body, such as the bloodstream, Janelle said. What makes CRE unique is that these bacteria have acquired the ability to produce enzymes that work against most antibiotics.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new report, the six patients ranged in age from 20 to 85, with an average age of 61. All of the patients had been diagnosed with urinary tract infections. (CRE can also cause pneumonia and blood infections.) The cases were identified from 2014 to 2016, and all of the patients survived.

All of the patients were infected with a type of CRE that produces an enzyme called New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase. The enzyme makes the bacteria resistant to certain antibiotics, including the powerful carbapenem class of antibiotics. This type of CRE is not very common in the United States, but some people have become infected when they received health care abroad.

Of the six patients in the new report, two had traveled internationally shortly before their diagnoses, one to an unknown country in Africa and one to the Bahamas, the report said.

Two of the patients had underlying medical conditions, another risk factor for CRE, but three patients had no such conditions. One patient was pregnant at the time she tested positive for CRE. Being pregnant is known to suppress the body's immune system, which can increase the risk of infection.

In addition, one patient who had an underlying medical condition reported having provided care for a family member at several different health care facilities before testing positive for CRE, the report said.

Another risk factor for CRE infection is taking antibiotics. Studies have shown that when a person's normal gut bacteria community is disturbed (which happens when antibiotics are used), it puts that individual at risk for becoming sick with "bad" bacteria, including CRE. In addition, use of antibiotics increases the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance to the drugs, either through a mutation or by acquiring genes from other bacteria.

"Any time antibiotics are used, this puts biological pressure on bacteria that promotes the development of resistance," Janelle said.

Of the six patients, two had taken antibiotics within the month before they tested positive for CRE and one had taken antibiotics 10 months prior to testing positive.

The findings point to the importance of prescribing antibiotics appropriately, Janelle said. Studies have shown that doctors sometimes prescribe antibiotics when the medicines aren't needed (such as when patients have a viral infection that can't be treated with antibiotics).

"Proper use of antibiotics can slow the development of resistance in bacteria and can preserve this life-saving resource," Janelle said.

The six cases do not appear to be connected, and the source of these CRE infections remains unknown, the report said.

To prevent CRE and other infection, members of the general public can wash their hands frequently and take antibiotics only when they are prescribed, Janelle said. Patients should also expect their health care providers to wash their hands or use hand sanitizer before touching patients, the CDC said. If the health care provider doesn't do this, patients should ask them to do so, the agency said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.