Baby 'Spiders' on Mars Expand Across Sand Dunes (Photos)

A NASA Mars probe may have snapped rare baby photos of the Red Planet's bizarre "spiders."

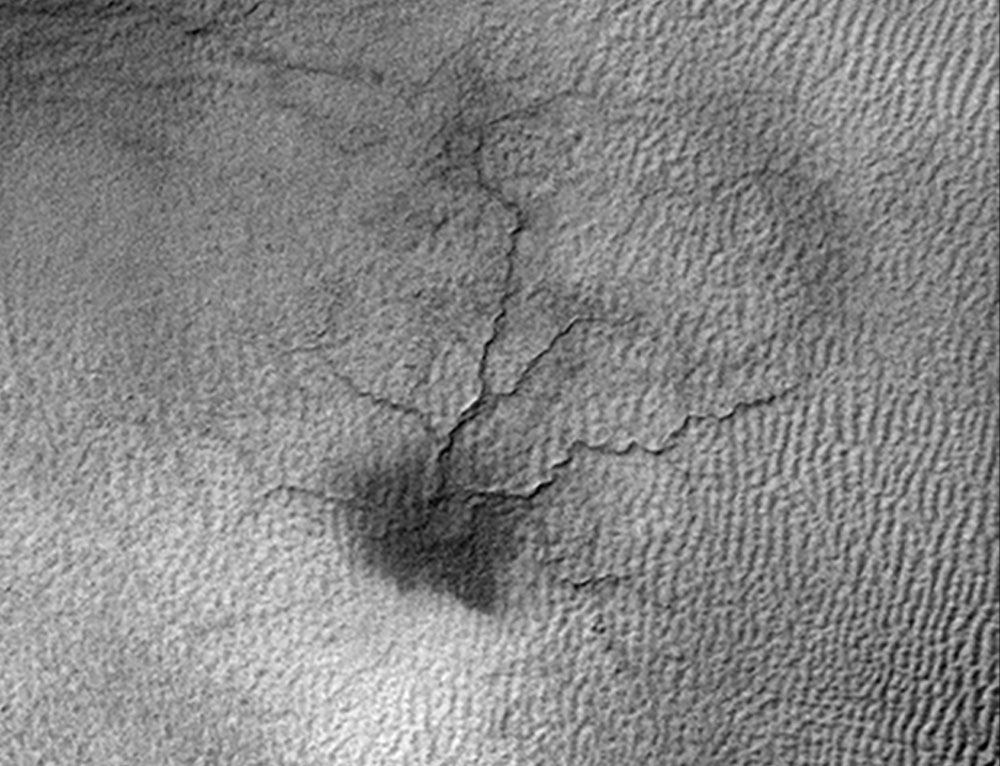

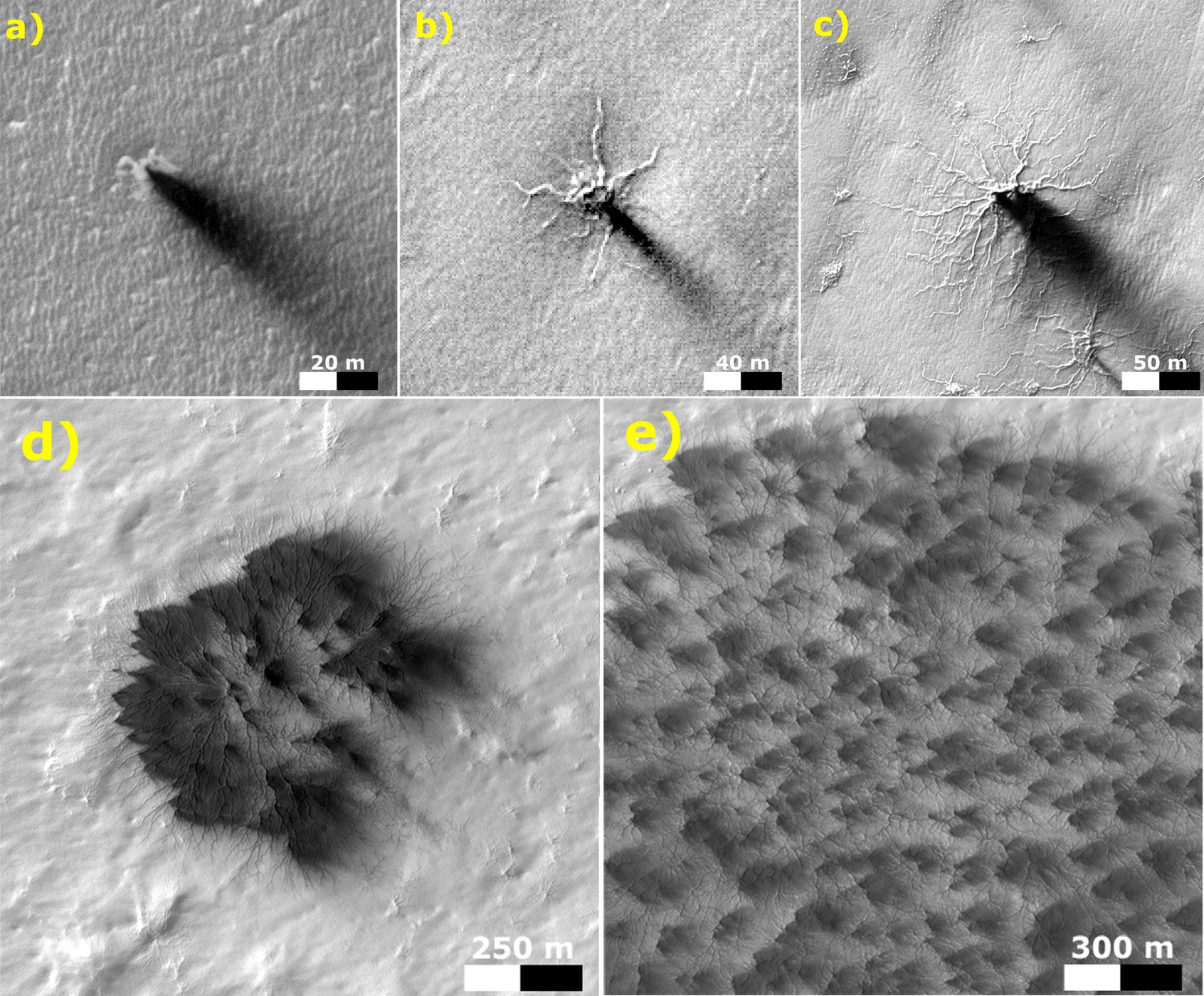

The images, captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), show small, erosion-carved cracks in Red Planet sand dunes. The features may be infant versions of the similar-looking but larger Martian channel-networks that have been dubbed spiders, a recent study suggested.

"We have seen for the first time these smaller features that survive and extend from year to year, and this is how the larger spiders get started," study lead author Ganna Portyankina, of the University of Colorado Boulder said in a statement. "These are in sand-dune areas, so we don't know whether they will keep getting bigger or will disappear under moving sand." [Latest Photos from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter]

The spiders have been spotted only near the Martian south pole. During Mars' southern winter, carbon dioxide ice caps cover this area. When the ice thaws in the spring, deep troughs are carved into the terrain. The crevices vary in size, and multiple channels generally converge at a central point, creating surface features that resemble giant arachnids.

The new images, which MRO took with its High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, allow scientists to chart the year-to-year growth of the potential baby spiders for the first time ever, NASA officials said.

HiRISE images captured over the span of three Martian years (which is equal to about 5.7 Earth years) show a growing network of branching channels on sand dunes. While these channels appear to be relatively small, they may help scientists learn more about how the larger spider features form, NASA officials said.

In fact, based on the rate at which the smaller channels have grown over the last three Martian years, researchers estimate it would take more than 1,000 Martian years to sculpt a typical spider feature, said the study, which was published Sept. 22 in the journal Icarus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Similar grooves have previously been spotted on sand dunes near Mars' north pole; however, those features lasted no longer than a year, as surrounding sand filled them in. The newly reported channels, on the other hand, have grown year to year and formed a branching pattern that closely resembles full-scale spider terrain, NASA officials said.

"There are dunes where we see these dendritic [or branching] troughs in the south, but in this area, there is less sand than around the north pole," Portyankina said in the statement. "I think the sand is what jump-starts the process of carving a channel in the ground."

Sandy terrain is soft enough to be carved by the thawing carbon dioxide, but in order for the channels to persist and expand from year to year, the underlying ground must be relatively hard. Otherwise, loose sand refills the carved terrain and the channels cannot grow into the full-scale spiders observed near Mars' south pole, NASA officials said.

"The combination of very high-resolution imaging and the mission's longevity is enabling us to investigate active processes on Mars that produce detectable changes on time spans of seasons or years," MRO deputy project scientist Leslie Tamppari, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the NASA statement. "We keep getting surprises about how dynamic Mars is."

Original article on Space.com.