Forget About Global Warming Pause — It Doesn't Exist

Forget about the so-called climate change hiatus — a period beginning in 1998 when the increase in the planet's temperature reportedly slowed — it doesn't exist, according to a new study that found the planet's ocean temperatures are warming faster than previously thought.

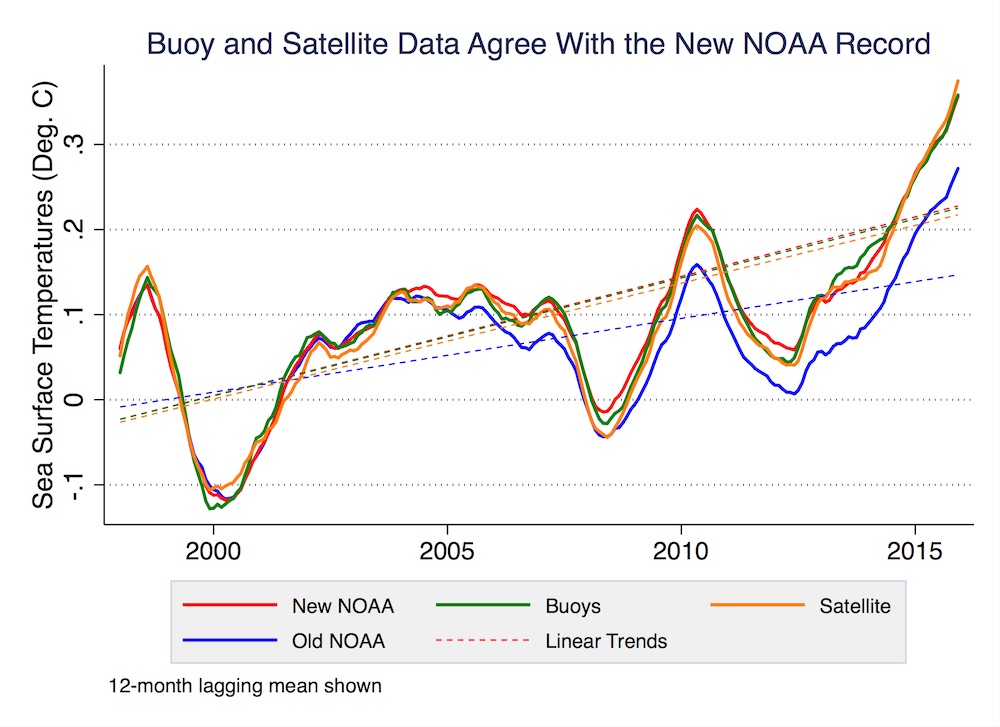

The findings support similar results from a 2015 study published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the journal Science. However, doubters of climate change attacked that study, prompting the researchers of the new study to examine the data anew.

"Our results mean that essentially NOAA got it right, that they were not cooking the books," study lead author Zeke Hausfather, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley's Energy and Resources Group. [The Year in Climate Change: 2016's Most Depressing Stories]

Climate change hiatus

The climate change hiatus was more of a suspected "slowdown, not a disappearance of global warming," as the world's oceans were still warming, but at a lesser rate than previously predicted, according to Climate Central. However, many scientists acknowledged the slowdown, which allegedly took place from 1998 to 2012. Climate change doubters also took note, and used the slowdown as evidence that climate change was a hoax, the researchers of the new study said.

But in 2015, NOAA published an analysis showing that the slowdown wasn't real, and was the result of measurement errors. The modern buoys that measure ocean temperatures tend to report slightly cooler temperatures than older ship-based systems, even when measuring the same part of the ocean, the NOAA researchers found.

That's because in the 1950s, ships began to measure water piped through the engine room, which is usually a warm place. In contrast, today's buoys report slightly cooler temperatures because they measure the water directly from the ocean, Hausfather said.

"The observations have gone from 80 percent ship-based in 1990 to 80 percent buoy-based in 2015," the researchers wrote in the study. As this switch happened, it appeared that there was a warming slowdown in the ocean — largely because researchers didn't account for the ships' warm bias when combining the buoy and ship data sets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the NOAA researchers corrected for the bias, they found that the oceans had warmed 0.22 degrees Fahrenheit (0.12 degrees Celsius) per decade since 2000, a rate almost twice as fast as earlier estimates of 0.12 F (0.07 C) per decade. Moreover, the newfound rate matched estimates for the previous 30 years, from 1970 to 1999, the researchers said

But once the NOAA study was published, a U.S. House of Representatives committee subpoenaed the scientists' emails, said Hausfather, who was not involved in the 2015 study. NOAA provided data and responded to scientific questions, but did not comply with the subpoena, as many said it would have a "chilling effect" on science, according to a UC Berkeley statement.

Independent study

In order to see whether the NOAA researchers got it right, Hausfather and his colleagues took an independent look at ocean temperatures by using data from satellites, robotic floats (called Argo floats) and buoys.

The approach is different than the one the NOAA took, which was an attempt to combine the old ship measurements with data from new buoys. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

"Only a small fraction of the ocean measurement data is being used by climate monitoring groups, and they are trying to smush together data from different instruments, which leads to a lot of judgment calls about how you weight one versus the other, and how you adjust for the transition from one to another," Hausfather said in the statement. "So we said, 'What if we create a temperature record just from the buoys, or just from the satellites, or just from the Argo floats, so there is no mixing and matching of instruments?'"

In every scenario — whether the data was from the satellites, buoys or the Argo floats— the researchers found that the warming ocean trends matched those found in the NOAA study. Their findings provide more evidence that the oceans have warmed 0.22 F per decade over the past 20 years, the researchers said.

In other words, the rising trend in temperatures is seen in the last half of the 20th century and continued through the first 15 years of the 21st, meaning there was no hiatus, the researchers said.

"In the grand scheme of things, the main implication of our study is on the hiatus, which many people have focused on, claiming that global warminghas slowed greatly or even stopped," Hausfather said. "Based on our analysis, a good portion of that apparent slowdown in warming was due to biases in the ship records."

Correcting biases

Last year, NOAA published another study in the journal Science, which gave more weight to temperature measurements collected by buoys than by ships. NOAA also accounted for changing shipping routes and measurement techniques, all of which are valid ways to correct for measurement biases, the researchers of the new study said.

Hausfather and his colleagues are urging researchers who study ocean temperature trends to take the new data into account. For instance, the Hadley Climatic Research Unit in the United Kingdom, another repository of oceanic temperatures, didn't completely account for the measurement changes, and so their data show a slightly lower rate of warming than the NOAA and the new study's results, Hausfather and colleagues said.

"In the last seven years or so, you have buoys warming faster than ships are, independently of the ship offset, which produces a significant cool bias in the Hadley record," Hausfather said. In the new study, the researchers urge the Hadley center to fix this bias, he said. [The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted]

"People don't get much credit for doing studies that replicate or independently validate other people's work," Hausfather said. "But, particularly when things become so political, we feel it is really important to show that, if you look at all these other records, it seems these researchers did a good job with their corrections."

Study co-author Mark Richardson, a climate scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, agreed.

"Satellites and automated floats are completely independent witnesses of recent ocean warming, and their testimony matches the NOAA results," Richardson said. "It looks like the NOAA researchers were right all along."

The study was published online today (Jan. 4) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.