A spongy new super-material could be lighter than the flimsiest plastic yet 10 times stronger than steel.

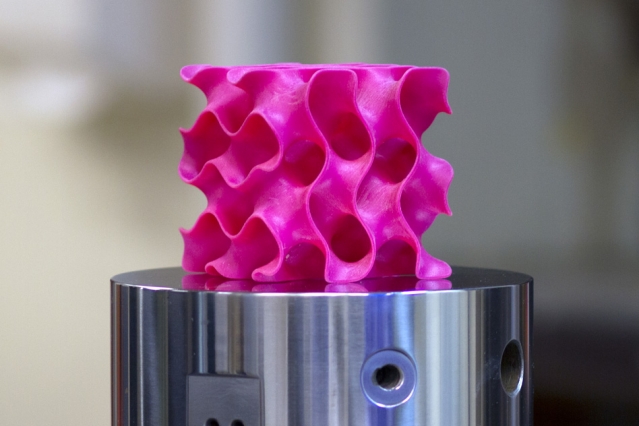

The new super-material is made up of flecks of graphene squished and fused together into a vast, cobwebby network. The fluffy structure, which looks a bit like a psychedelic sea creature, is almost completely hollow; its density is just 5 percent that of ordinary graphene, the researchers said.

What's more, though the researchers used graphene, the seemingly magical properties of the material do not totally depend on the atoms used: The secret ingredient is the way those atoms are aligned, the scientists said.

"You can replace the material itself with anything," Markus J. Buehler, a materials scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) said in a statement. "The geometry is the dominant factor. It's something that has the potential to transfer to many things."

Graphene, a material made up of flaky sheets of carbon atoms, is the strongest material on Earth — at least in 2D sheets. On paper, ultrathin sheets of graphene, which are just an atom thick, have unique electrical properties and indomitable strength. Unfortunately, these properties don't easily translate to 3D shapes that are used to build things. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

Past simulations suggested that orienting the graphene atoms a specific way could enhance strength in three dimensions. However, when researchers tried to create these materials in the lab, the results were often hundreds or thousands of times weaker than predicted, the researchers said in the statement.

Stronger than steel

To address this challenge, the team got down to basics: analyzing the structure at the atomic level. From there, the researchers created a mathematical model that can accurately predict how to create remarkably strong super-materials. The researchers then used precise amounts of heat and pressure to produce the resulting curvy, labyrinthine structures, known as gyroids, which were first mathematically described by a NASA scientist in 1970.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Actually making them using conventional manufacturing methods is probably impossible," Buehler said.

The material's strength comes from its enormous surface-area-to-volume ratio, the researchers reported in a study published Jan. 6 in the journal Science Advances. In nature, sea creatures like coral and diatoms also leverage a large surface-area-to-volume ratio to achieve incredible strength at tiny scales.

"Once we created these 3D structures, we wanted to see what's the limit — what's the strongest possible material we can produce," study co-author Zhao Qin, a civil and environmental engineering researcher at MIT, said in the statement.

The scientists created a series of models, built them, and then subjected them to tension and compression. The strongest material the researchers created was about as dense as the lightest plastic bag, yet stronger than steel.

One obstacle to creating these superstrong materials is the lack of industrial manufacturing capability for producing them, the researchers said. However, there are ways the material could be produced at larger scales, the scientists said

For instance, the actual particles could be used as templates that are coated with graphene through chemical vapor deposition; the underlying template could then be eaten or peeled away using chemicals or physical techniques, leaving the graphene gyroid behind, the researchers said.

In the future, massive bridges could be made of gyroid concrete, which would be ultrastrong, lightweight, and insulated against heat and cold because of all the myriad air pockets in the material, the researchers said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.