Black Holes Regurgitate 'Spitballs' After Devouring Stars

When a black hole devours a star, it spews planet-size "spitballs" of regurgitated gas tumbling through the galaxy — and some of these globs can come within a few hundred light-years of Earth, new research shows.

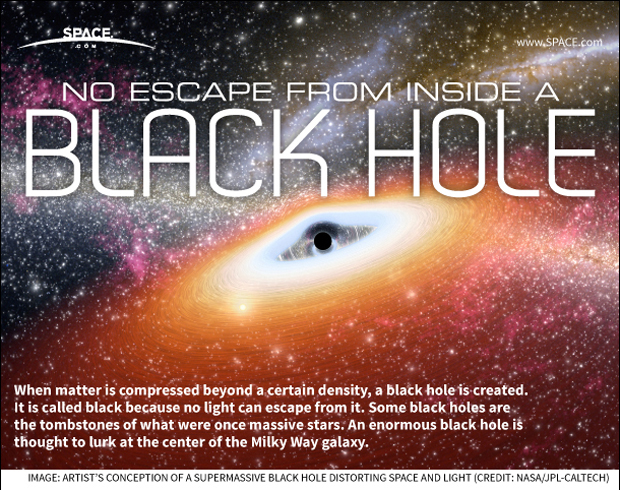

Supermassive black holes lie at the center of almost every galaxy, including the Milky Way. The massive cosmic bodies have a powerful gravitational force that pulls in nearby wandering stars, tears them to shreds and, as a result, spews out a stream of hot gas that can clump together to form planet-size objects, according to a statement from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

"A single shredded star can form hundreds of these planet-mass objects," Eden Girma, an undergraduate student at Harvard University and lead author of the study, said in the statement. "We wondered: Where do they end up? How close do they come to us? We developed a computer code to answer those questions." [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

The researchers found that these "spitballs," whose closest emissaries might reach within a few hundred light-years of Earth, weigh as much as several Jupiters. However, the objects are very different from planets, as they are made solely of leftover star material and form much more rapidly.

"It takes only a day for the black hole to shred the star (in a process known as tidal disruption) and only about a year for the resulting fragments to pull themselves back together," CfA researchers said in the statement. "This is in contrast to the millions of years required to create a planet like Jupiter from scratch."

The "spitballs" travel at speeds of about 20 million mph (32 million km/h), and would therefore take roughly a million years to reach Earth's neighborhood after being launched from a black hole, officials said in the release. However, most of them leave our galaxy entirely; the researchers estimated that almost 95 percent of them would be propelled to other galaxies, where similar tidal-disruption processes are thought to exist.

"Other galaxies, like Andromeda, are shooting these 'spitballs' at us all the time," study co-author James Guillochon, an astrophysicist at the CfA, said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists plan to survey the "spitballs" in the future using instruments such as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (currently under construction in Chile) and the James Webb Space Telescope (set to launch in 2018), which will have a better chance of detecting the faint glow of the objects hurtling through space. However, it will still be difficult to distinguish a cosmic "spitball" from free-floating planets, the researchers noted.

"Only about one out of a thousand free-floating planets will be one of these second-generation oddballs," Girma said in the statement.

Girma presented the study findings at the 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, held Jan. 3 to Jan. 7 in Grapevine, Texas.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.