#DoesItFart: Database Answers Your Burning Questions About Animal Gas

Spurred by an innocent query recently posed to a biologist on Twitter, scientists are assembling an unusual database of animal life to answer the burning question, "Does it fart?"

The online open-access spreadsheet of smells began as the Twitter hashtag #DoesItFart, and gathers examples submitted by dozens of researchers confirming or denying the gassy output of a wide range of animals, from African wild dogs ("Any self-respecting canine does") to wood lice ("Excrete ammonia").

In comedy, fart jokes are generally considered to be scraping the bottom of the barrel. But when it comes to animals and the gas they pass, experts who study them aren't full of hot air. Biologists' observations of animal farts — in the wild and under controlled conditions — can offer insight into dietary habits and inform scientists' understanding of what animals eat and how efficiently they digest their food. You might even say that thinking critically about farting just makes scents. [The Role of Animal Farts in Global Warming (Infographic)]

The first rumblings of #DoesItFart emerged from a Twitter conversation between two biologists. Dani Rabaiotti, a doctoral candidate with the Institute of Zoology at the Zoological Society of London, couldn't answer a family member's question about whether snakes could fart. So she tweeted at David Steen, an assistant research professor at the Auburn University Museum of Natural History in Alabama, who often fields questions on Twitter about snakes.

Their exchange was spotted by Nicholas Caruso, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alabama. Caruso had seen similar questions for other animals, and thought, "This should be a hashtag," he told Live Science in an email.

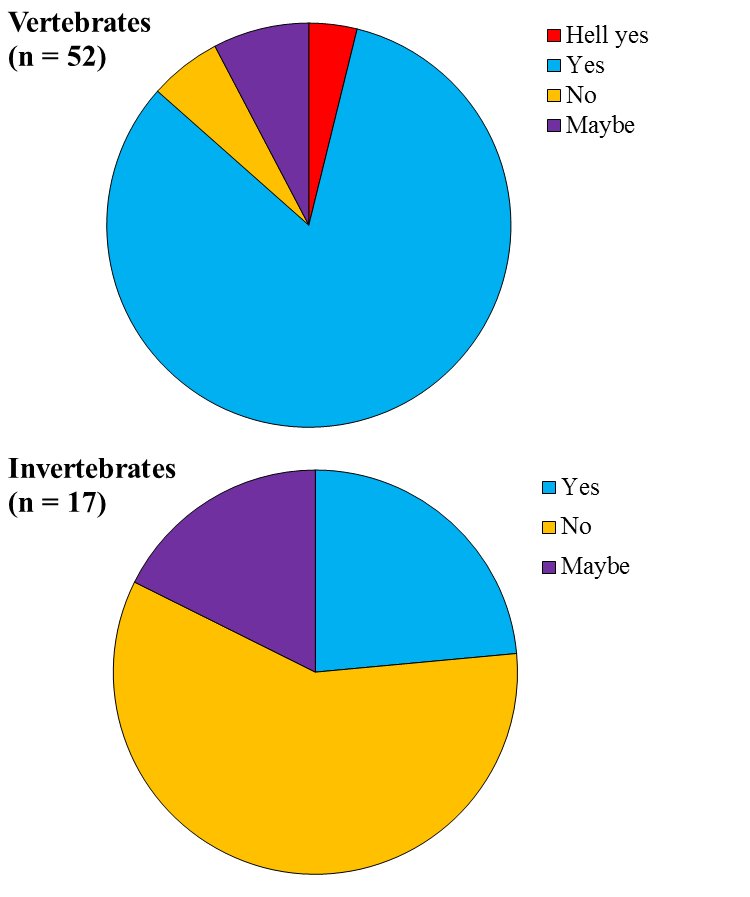

And thus, #DoesItFart emerged and spread across Twitter in a silent but deadly fashion. Its enthusiastic reception from biologists prompted Caruso to launch the #DoesItFart spreadsheet.

"I think a lot of biologists on Twitter — myself included — try not to take ourselves too seriously, and have fun with what we do," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One tweet shared by conservationist Chris Pellecchia, a doctoral candidate at the University of Southern Mississippi, helpfully included a video clip of a rhinoceros iguana partly submerged in water, to better demonstrate its adorable power puffs.

Caruso was surprised to see how many people — scientists and nonscientists alike — responded positively to the hashtag and the database, but he appreciated how humor — especially scatological humor — can be an effective way to raise people's interest in animal biology.

"I'm glad that people are engaging, though," Caruso said. "Anytime the public wants to talk to scientists, even if it is a silly topic like farts, is a good thing, in my opinion."

A handful of whimsical spreadsheet entries were clearly included for their comedic value — one anonymous wag uploaded "unicorns," claiming that their farts resemble "glitter and rainbows soft serve."

But the majority of the animal examples were provided by biologists, many of whom included anecdotal data to offer a more visceral sense of their entry's effluvia.

In case you were wondering, a seal fart "smells like lutefisk" — a gelatinous serving of dried fish soaked in lye — Rabaiotti added to the database.

And spotted-hyena farts are "especially bad after eating camel intestines," wrote carnivore biologist Arjun Dheer, a researcher with the Centre for Biological Sciences at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

Other entries describe frog farts ("pungent"), chameleon farts ("audible and stinky"), tapir farts ("in great amplitude") and rat farts ("They smell worse than dog farts").

And animals don't have to be large — or even have backbones — for their farts to have a big impact, according to marine ecologist Jeff Clements, a postdoctoral fellow with the Atlantic Veterinary College at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Recent studies have measured the impact of millipede farts on the animals' immediate environment, and have analyzed how much earthworms may contribute to greenhouse gases through the release of gases produced in their gut, Clements told Live Science in an email.

Animal farts can even be linked to large-scale environmental issues, such as ocean acidification, he added. Herring communicate through chemical cues in their farts, and recent changes in ocean chemistry due to increased absorption of carbon dioxide may be disrupting the herrings' communication signals.

"In theory, ocean acidification could change the chemical structure of herring farts, or change the way that individual herring perceive the farts of their kin, and this could in turn change their shoaling [social swimming] behaviour," Clements explained. "This is something that I'm realistically interested in pursuing, as my research interests lie in how global climate change can impact the behaviour of marine animals."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.