'Twilight' Star Kristen Stewart Co-Authors Artificial-Intelligence Paper

Actor Kristen Stewart, known for her portrayal of Bella in the "Twilight" movie franchise and director of "Come Swim" at the Sundance Film Festival, now has another line on her résumé: co-author of a computer science paper.

The paper, published online in the preprint journal ArXiv, is called "Bringing Impressionism to Life with Neural Style Transfer in Come Swim." The authors describe a set of programming shortcuts that can make movie shots look as though they were painted or drawn in a certain style, such as impressionism or pointillism.

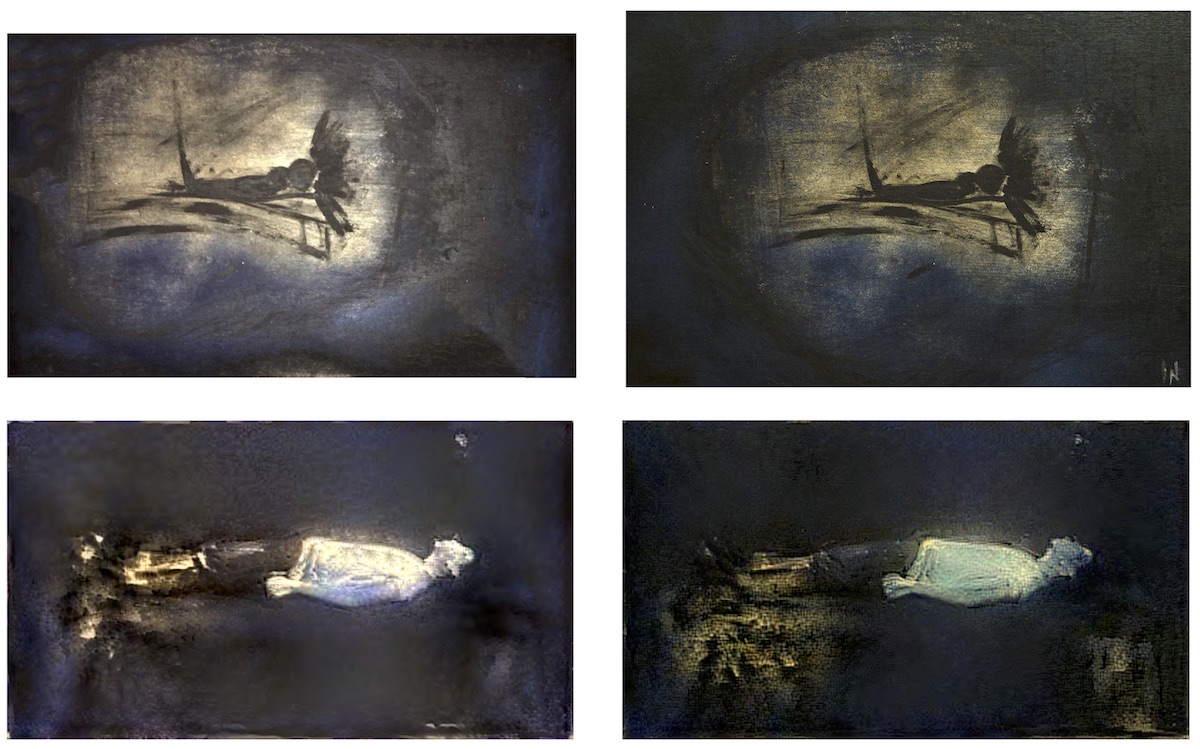

The process relies on machine learning, a type of artificial intelligence, and gave certain shots in the film short, which uses allusive images to follow a man through his day, the look of an impressionistic painting. The shot described in the paper is about 15 seconds long, and the painting is by Stewart herself. [5 Intriguing Uses for Artificial Intelligence (That Aren't Killer Robots)]

Stewart is the second author on the paper, with Bhautik Joshi, a research engineer at Adobe Systems, as the lead author, and David Shapiro, a producer at Starlight Studios, as the third author.

Neural style transfer

The technique described in the paper, called neural style transfer, differs from Instagram or Snapchat filters. "What current filters do is, they work with the information in the image," Joshi told Live Science. "A global operation like Instagram is just a color lookup." To create effects, Snapchat and Instagram use filters that are based on rules created by a human being; "if you come across this condition, do that to the image," he said.

For example, in Snapchat, the software is "trained" to recognize eyes in a photo, so if you want to make a person's eyes look like a cartoon character's, it can do that (or, in one filter, switch the eyes between two faces).

In contrast, style transfer, in this context, works by taking an image and breaking it down into blocks to identify its components and then comparing it to a reference image. So, for example, maybe you have a copy of Van Gogh's "Starry Night" and want to make another image look as though it were painted in the same style. The software would look for corresponding features in the image that you want to alter, using a technique based on so-called neural networks. Sometimes, the results can be unpredictable, because unlike with the Snapchat filters, the computer is learning as it goes through the images, Joshi said. [Gallery: Hidden Gems in Renaissance Art]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Neural networks are programs that work more like a human brain, learning and reinforcing certain behaviors by repeating an operation many times under slightly different conditions. (So, for example, a neural network might learn to identify a tree by looking at lots of images of trees, and then be asked to identify one to see if it had learned successfully.) The theory has been around since the 1940s, but it wasn't until about 20 years ago that computers became powerful enough to make use of it, according to Joshi.

The disadvantage with style transfer, though, is that it is computationally intensive, Joshi said. Even with powerful machines, it can take a lot of time to get a result that the artist (in this case, the film director) wants.

Making 'Come Swim'

Because Stewart knew approximately what look she wanted in "Come Swim," Joshi told the software to ignore several pathways it could have taken in order to limit the computing to a few options within the styles it could transfer.

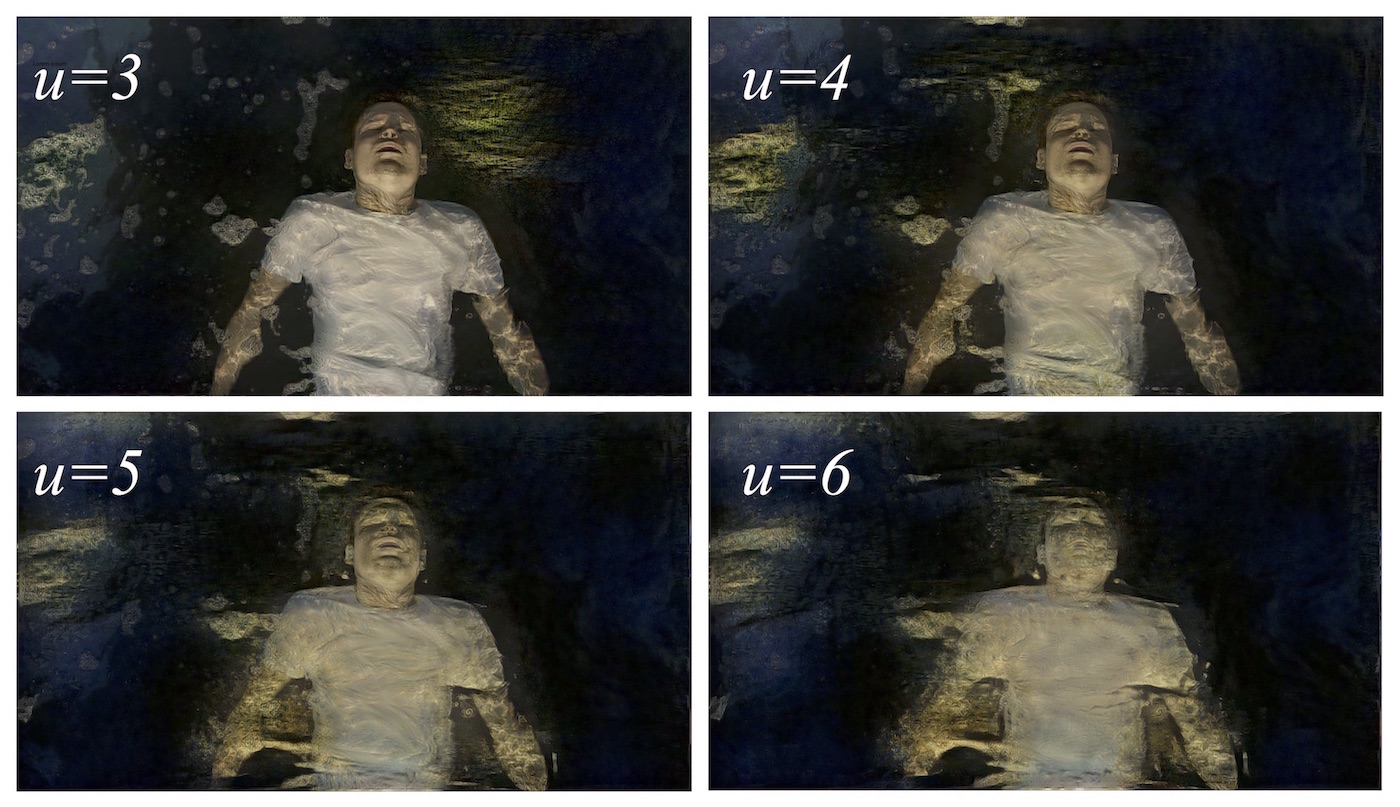

"The algorithm is essentially a black box," Joshi said. "Randomly sampling all these looks — that would get us nowhere. So we wanted to approach it in a structured way. We said, 'What is a reasonable range for this?' until we converged on the look, and made our iterations more predictable."

For instance, Joshi kept the "style transfer ratio" fixed, meaning the size of the block in the reference image that was transferred to the target image remained consistent.

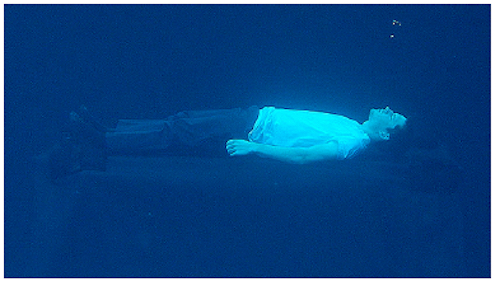

"The size of the block transferred can be adjusted," Joshi said. "You basically start with something — present [the] director with a starting point, and you iterate to get the imagery to a point to get the emotional response you want." Eventually, the computer generated an image Stewart was happy with — one of a man lying on his back in the water.

Although Joshi carried out all of the computational work, Stewart made it happen, approaching the work as a film director and visual artist, Joshi said. And although their modified technique isn't a fundamental breakthrough, it's a way to make certain kinds of work easier. New tools can be complicated to use, and sometimes, the choices can be overwhelming, Joshi said.

"The goal was to give other folks this new form of creative expression," he said. "Here's a couple of steps to take to make it less daunting."

Original article on Live Science.