'Alien' Life Could Exist High in Earth's Atmosphere

Life on Earth shows up in surprising places. It's been found in high-temperature vents deep undersea and high in the air. But we're still trying to learn more about these so-called "extremophiles." Researchers are now pondering how well can life reproduce in these environments. Also, could microbes of this type be found on other worlds?

In March, a group of University of Houston students — piggybacking on a payload with a prime mission to scope out auroras — will fly a high-altitude experiment from Alaska to see what microbes are in the high atmosphere, between 18 km and 50 km (11 miles and 31 miles) from the ground. The instrument, which looks almost like a small laundry hamper, pops open to collect what's in the atmosphere. Then, as the balloon descends, it shuts closed for researchers to analyze.

Jamie Lehnen, a fourth-year student on the team, says this system could be less open to contamination than pumps and other complicated mechanisms that require servicing on Earth. But it's the first time her group has used it, so isn't sure how well it will function. If it does, however, she's interested in learning about how microbes will react under the stresses of living at high altitudes.

"A lot of times, these microbes when they go up there, they shut down. They are not replicating and they are not metabolically active," she said. "I'm interested in how their stress response is similar to those [microbes] back on Earth's surface."

RELATED: Distant Rocky World Could Be Friendly for Life

Some of the earliest high-altitude microorganism experiments did not involve air travel at all — Charles Darwin picked up African dust on his ship while crossing the Atlantic Ocean, while Louis Pasteur made measurements on top of alpine glaciers. Both found microorganisms.

That said, microorganism research in the upper atmosphere has been active since the 1930s at least. One of the earliest flights involved Charles Lindbergh, a pilot best known for piloting the Atlantic solo in 1927. Accompanied with his wife, Lindbergh periodically passed the monoplane controls over to her to take samples from the atmosphere around them. The research team found spores of fungi and pollen grains, among other specimens.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Planes still require a substantial amount of atmosphere to fly, so it's with high-altitude balloons and rockets that we can get even higher — to the stratosphere and the mesosphere. According to NASA microbial researcher David Smith, some of the pioneering work in this field was done in the 1970s, particularly in Europe and the Soviet Union. "Everything they did was fascinating, but there hasn't been a lot of follow-up work to validate the results of those collections," he told Seeker.

There are open questions about how valid these early results are, given that contamination protocols may not have been strict. So Smith and other researchers are trying to figure out what kind of microbes live above Earth, and for how long. In May and June, Smith's team will fly with the team from NASA ABoVE (Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment), which uses a Gulfstream III jet to monitor how climate change affects animals, plants, the environment and infrastructure. In the spring, a vast airstream on the Pacific Ocean moves millions of tons of dust across the ocean, mostly from Asia.

"We want to know what kind of microorganisms are making that leap across the ocean, co-transported with aerosol species," Smith said. "Alaska will allow us an opportunity to test the atmospheric bridge hypothesis, which simply speaking, is continents sneezing on each other."

Smith's team will use a cascade sampler for collection, which passes air through progressively finer impact plates with holes in them, he said. As the air moves through, dust and any microorganisms impact the surface of those plates. A portion of them stick to the surface, allowing researchers to analyze what is there afterwards.

Smith is skeptical that microorganisms are growing or dividing at such high altitudes, because it's so cold and dry up there. But he says that microorganisms may be "persisting", or lingering and not being killed. "Nobody's been able to measure how long microorganisms can stay in the stratosphere. There's works that still needs to be done."

"Virtually all terrestrial and marine surfaces have microorganisms associated with them that can get disattached from the surfaces by wind or other physical disturbances," wrote Aarhus University assistant professor Tina Santl-Temkiv, who has studied microorganisms in hailstones, in an e-mail to Seeker.

"[They] can reach higher levels of troposphere, above around one kilometer, can stay suspended in air for around a week and can travel thousands of kilometers, riding on wind currents. Eventually, they get deposited back to the ground wither through the formation of rain or simply due to gravity."

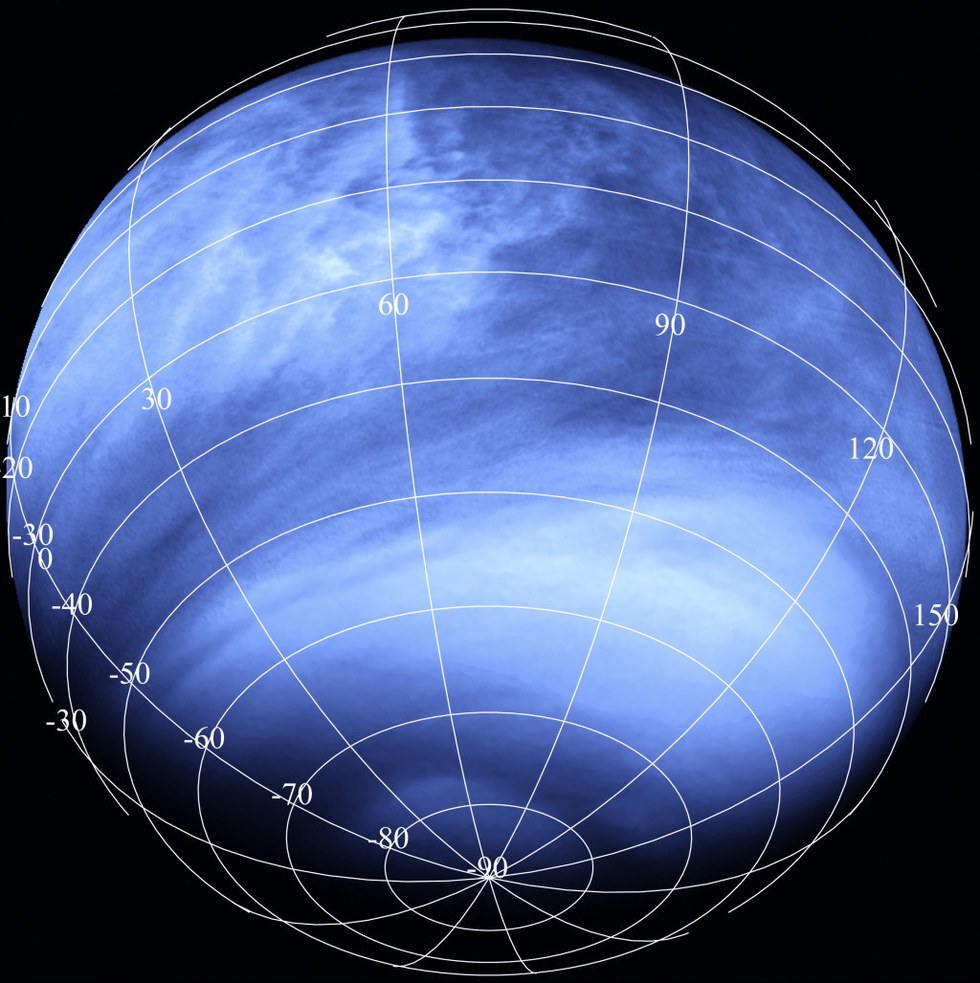

If Earth's atmosphere is shown to be a great spot for life to divide, however, it could have implications for locations such as Venus. Back in the 1960s, astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan suggested that the upper atmosphere of Venus could harbor the descendants of organisms that could have evolved on the surface of the planet when it was cooler.

RELATED: Does Alien Life Thrive in Venus' Mysterious Clouds?

Even though today the surface can crush and cook unprotected spacecraft, 50 kilometers (31 miles) above is more temperate. Moreover, researchers have found an intriguing substance that blocks ultraviolet light in Venus' clouds. Life hasn't yet been ruled out as a possibility.

"Venus and Earth were similar for 3 billion years [of their evolution] and perhaps as recently as up to about half a billion years ago," said Dr. Lynn Rothschild, a NASA astrobiologist and synthetic biologist that is on Smith's research team. She said this includes liquid oceans, similar atmosphere, and probably the same sorts of minerals and organic compounds as well.

But Venus would be a difficult prospect if the life returns to the surface. The sun got more luminous as the solar system aged, evaporating the water from Venus' oceans. The water vapor, now in the atmosphere, contributed to giving Venus a hellish greenhouse effect on its surface.

It seems that life is hardy, but we don't know if it's tough enough to survive living high above a planetary surface. If it does, however, that could mean that even missions that sample a planet's atmosphere could have to worry about protections against hurting possible life. We'll have to see what these new experiments yield, though, before reaching any conclusions.

WATCH VIDEO: The Mystery Of Venus' Green Glow

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.