24 Amazing Archaeological Discoveries

Love archaeology but hate dust, dirt and human remains? You're in luck. The following list of amazing archaeological finds will take you on a trip through time and across the globe, but without all the mess (or the jetlag).

From the great, lost library of King Ashurbanipal to the toxic tomb guarded by the terracotta warriors of Shaanxi, here are the 24 most incredible archaeological findings of all time.

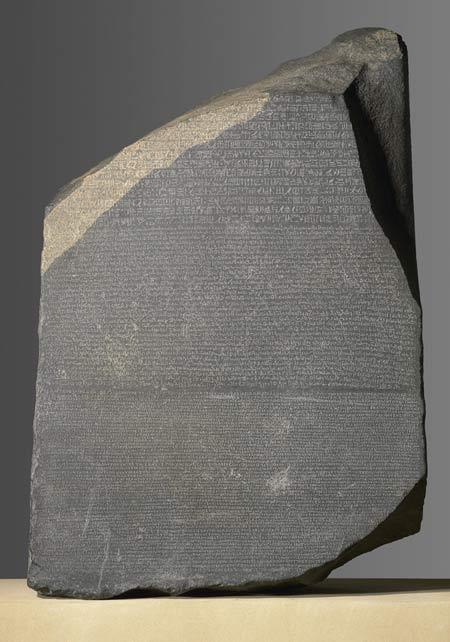

Rosetta Stone

In 1799, a group of French soldiers rebuilding a military fort in the port city of el-Rashid (or Rosetta), Egypt, accidentally uncovered what was to become one of the most famous artifacts in the world — the Rosetta Stone. The ancient slab was carved in 196 B.C. and bears a royal decree issued by priests on behalf of Ptolemy V, then ruler of the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt.

But the stone's message isn't what makes it famous; it's how that message is written. The decree on the Rosetta stone is inscribed in three scripts: ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Egyptian demotic script and ancient Greek. In 1822, Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs on the stone, enabling future translations of other texts written in the ancient Egyptian language and reviving the lost history and culture of ancient Egypt.

Since 1802, the Rosetta Stone has resided at the British Museum in London.

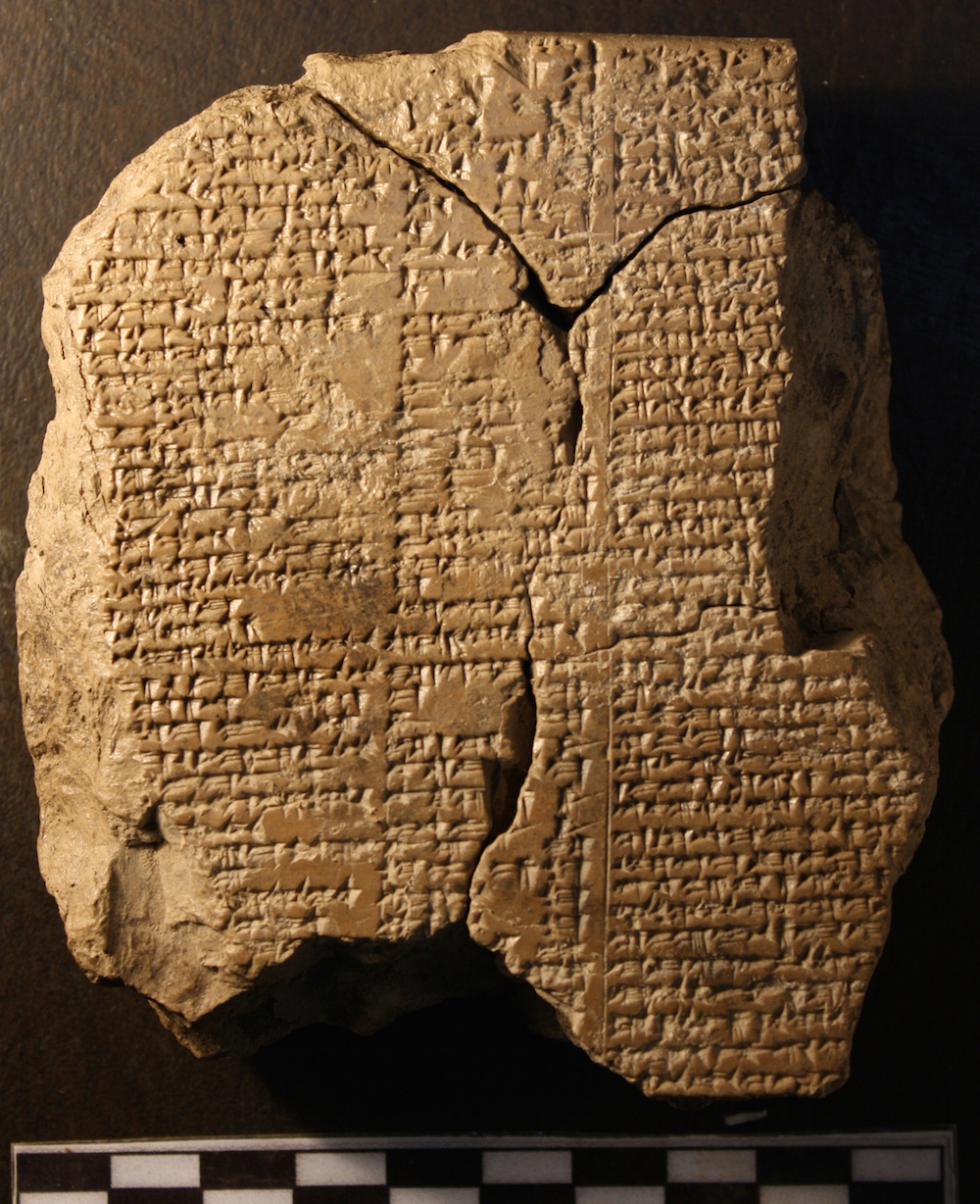

The Library of Ashurbanipal

Bookworms, get ready to swoon. In the 1850s, archaeologists in Kuyunjik, Iraq, uncovered a treasure trove of clay tablets inscribed with text from the seventh century B.C. The ancient "books" belonged to Ashurbanipal, who ruled the ancient kingdom of Assyria from 668 B.C. to around 630 B.C. Among the more than 30,000 pieces of writing were historical texts, administrative and legal documents, medical treatises, "magical" manuscripts and literary works, including the "Epic of Gilgamesh" (shown here).

The texts have "unparalleled importance" in the study of ancient cultures of the Near East, according to the British Museum, where many pieces from the Library of Ashurbanipal are currently housed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Troy

Few archaeological sites are as hotly debated as Troy, the ancient city where, according to Homer's "Illiad," the Trojan War between the kingdoms of Troy and Mycenaean Greece took place. Scholars disagree on whether this legendary war actually occurred and, if it did, if it took place at the site that many people now identify as the ancient city of Troy.

The city is believed to have stood on a site known as Hisarlik on the northwest coast of Turkey. The notion that this particular site was once the city of Troy is rooted in thousands of years of history and mythology. But in the early 19th century, an archaeologist named Heinrich Schliemann popularized the idea worldwide after a series of excavations at Hisarlik unearthed treasures that Schliemann claimed belonged to King Priam, the ruler of Troy at the time of the Trojan War.

While archaeologists cannot be completely certain that Hisarlik is the Troy of legend, they do know that the site was inhabited for thousands of years (from 3,000 B.C. to A.D. 500). In fact, Hisarlik was the location of at least 13 different cities, each one built upon the ruins of the city that came before it, according to archaeologists.

King Tut's Tomb

Mystery and intrigue surround the next archaeological discovery on our list — that of the tomb of Tutankhamun, or King Tut. The Egyptian pharaoh's lavish burial chamber was discovered in 1922 by a team of archaeologists led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter.

Tutankhamun came to power around 1332 B.C. at age 9 and died about nine years later. His unexpected death may explain why the boy pharaoh's tomb appears to have been completed in a hurry. Microbes found on the wall of the tomb suggest that the paint on the walls wasn't even dry when the tomb was sealed, archaeologists say.

When Carter and his team entered King Tut's tomb for the first time, they were confronted with a variety of treasures, including two "ebony-black" effigies of the king and an array of gold-covered couches carved into the shapes of exotic animals. The treasures of the tomb were so incredible that Carter and his team helped protect them from grave robbers by perpetuating a myth that anyone who entered the tomb would suffer under the dead pharaoh's curse. But this alleged curse hasn't stopped archaeologists from continuing to explore the famous burial chamber nearly 100 years later.

Machu Picchu

One of the most popular archaeological sites on Earth, Machu Picchu is a 15th-century Inca site seated high on a mountainside in Peru. The late Hiram Bingham III, a professor at Yale University, rediscovered the site in 1911. Until then, the ancient ruins had gone under the radar of Spanish conquistadors and settlers, leaving them remarkably well preserved.

Many archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was once the royal estate of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, a 14th-century Inca ruler. The large complex covers an area of about 126 square miles (326 square kilometers) and includes walls, terraces, houses and several temples.

Pompeii

In A.D. 79, an erupting Mount Vesuvius enveloped the Roman city of Pompeii in a cloud of volcanic gases and debris, killing any of the city's residents who did not manage to flee. The remains of the city and its citizens were buried under a layer of pumice stone and ash some 19 to 23 feet (6 to 7 meters) deep, according to Encylopædia Britannica.

Pompeii remained undisturbed for over a thousand years until, in the late 16th century, an architect named Domenico Fontana stumbled upon the ancient fresco-covered walls of a Pompeii residence while working on an infrastructure project. However, no further excavations were made at the site until the mid-18th century, when workmen digging a foundation for the summer palace of the King of Naples unearthed the remains of Herculaneum (a nearby town that had suffered the same fate as Pompeii). Pompeii itself was intentionally excavated not long thereafter. Centuries later, the city continues to be a popular attraction for tourists, and many artifacts from the site can be viewed at the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

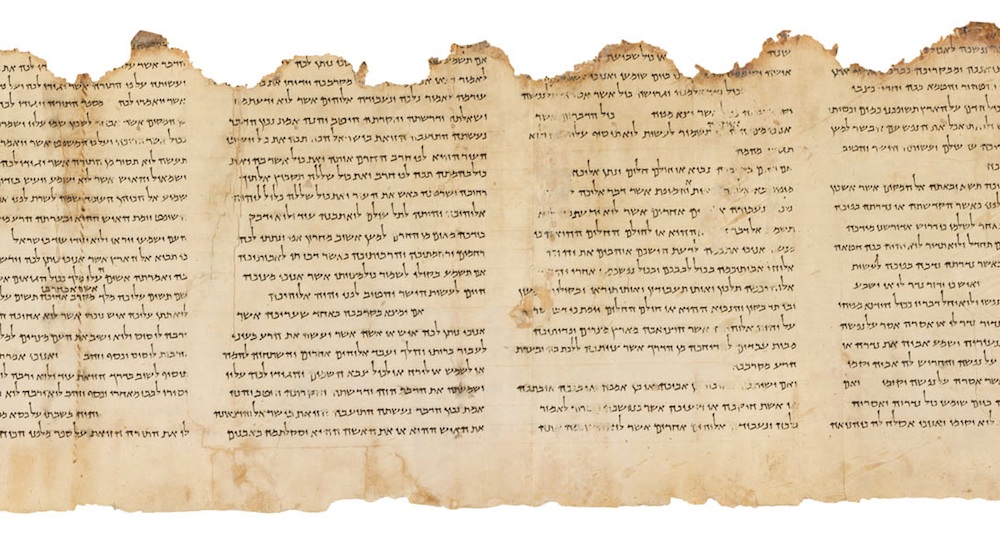

Dead Sea Scrolls

A young shepherd named Muhammed Edh-Dhib discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls by accident in the 1940s while looking for a stray goat near the ancient site of Khirbet Qumran. Located in the West Bank, near the Dead Sea, the first settlement at Qumran dates back about 2,600 years, but archaeologists believe the scrolls were penned between 250 B.C. and A.D. 68, according to the Biblical Archaeology Society, long after that first settlement had given way to a second settlement. [See Photos of Dead Sea Scrolls]

There were seven scrolls initially found by the shepherd inside of a ceramic jar in a cave near Qumran. Later, researchers and public officials discovered more than 900 other manuscripts in 11 caves in the surrounding area, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority. These scrolls include copies of Genesis, Exodus, Isaiah, Kings and Deuteronomy, as well as hymns, calendars and psalms. Some of the works represent the earliest known copies of parts of the Hebrew Bible. Many of the original copies are kept in Jerusalem, with several scrolls on public display at The Shrine of the Book, a wing of the Israel Museum.

Akrotiri, Thera

Pompeii is not the only ancient city to have been buried (and preserved) under a layer of ash and stone: The site of Akrotiri on the Greek island of Thera (now called Santorini) suffered a similar fate around 1500 B.C. The Bronze Age settlement was at the height of its development when an extremely powerful eruption of the Thera volcano covered all traces of the thriving metropolis in several meters of volcanic debris.

Some small-scale digging at Akrotiri first began in 1867, after locals discovered ancient artifacts at a quarry near the buried settlement. But a full excavation of the city wasn't carried out until 1967 under the direction of Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos. He and his team uncovered a large and wealthy settlement, replete with private homes, paved streets, indoor toilets and richly painted frescoes.

But there was one thing missing from the buried city — people. Marinatos and his team did not discover any human remains at Akrotiri, leading them to believe that residents likely had some warning of the deadly eruption that ultimately wiped out their city, according to the Canadian Museum of History.

There are those who believe that the ancient myth of the sunken city of Atlantis stems from the "lost" city of Akrotiri. Unlike Atlantis, however, you can visit Akrotiri in person and view artifacts from the site at the Museum of Prehistoric Thera in Fira, on the island of Santorini in Greece.

Olduvai Gorge

One of the most important archaeological sites in the world isn't a lost city or a treasure-filled tomb — it's a steep ravine in the Great Rift Valley in Tanzania. Known as Olduvai Gorge, the site holds the earliest evidence of the existence of human ancestors.

In the 1930s, a husband and wife team of paleoanthropologists (Louis and Mary Leakey) unearthed stone tools in Olduvai Gorge, as well as skull remains belonging to a 25-million-year-old Pronconsul primate. Then in 1959, Mary Leakey uncovered parts of a skull and upper teeth belonging to Paranthropus boisei, an early human ancestor, or hominin, which lived about 1.75 million years ago. At the time, P. boisei was the oldest hominin ever discovered. The Leakeys and their two sons also went on to discover another human ancestor, Homo habilis, in Olduvai Gorge.

In 1968, Peter Nzube discovered a 1.8-million-year-old Homo habilis skull at the site. And in 1986, a team of archaeologists from Tanzania and the United States unearthed hundreds of bones belonging to a H. Habilis female who also lived some 1.8 million years ago. These and other findings at Olduvai Gorge helped to confirm that the first humans evolved in Africa.

Terracotta Warriors

In 1974, Chinese farmers unearthed one of the biggest archaeological finds of the 20th century — the terracotta army of China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (259 B.C. – 210 B.C.). The clay warriors, as well as their chariots and horses, were painstakingly carved and then buried near the emperor's tomb to defend him in the afterlife. Other terracotta figures, including acrobats and musicians, were also buried with the late ruler.

Located underground near the city of Xi'an in China's Shaanxi province, this huge collection of ancient figures is situated less than a mile from the pyramid-shaped mausoleum of the first emperor. But the emperor's final resting place has never been excavated. [Photos: Terracotta Warriors Protect Secret Tomb]

Archaeologists think that the opulent tomb is huge — a 38-square-mile (98 square kilometers) replica of the city of Xi'an, complete with a network of waterways and topographic features, like mountains and hills. Scientists have used remote sensing and radar devices to learn more about this underground metropolis but have yet to enter the tomb because of health concerns. Descriptions of the tomb written a century after the emperor's rule suggest that the faux rivers and streams inside the tomb once flowed with toxic mercury, and the abnormally high mercury content of the soil near the tomb lends credence to these ancient accounts.

Ötzi the iceman

In 1991, hikers climbing a glacier in the Italian Alps stumbled upon the frozen remains of a man who lived over 5,000 years ago. Known as Ötzi, the glacier mummy has since been the subject of intensive research by scientists. [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Ötzi the Iceman]

Studies of the Copper Age mummy suggest that Ötzi was a shepherd, herding sheep, cows and goats near what is now the Italian-Austrian border. Scientists have concluded that Ötzi likely didn't live in the Alps, but rather spent most of his life in Isack Valley or the lower Puster Valley, in an area that is now part of northern Italy. And it's not just the ancient man's life that scientists are interested in; they're also keen to understand more about his death.

A study published in 2012 found that Ötzi bled to death after an arrow struck an artery in his shoulder. He also suffered a blow to the head during this fatal attack, according to researchers. Whether the shepherd fell and hit his head after the arrow struck him or was bludgeoned by his attackers remains a mystery.

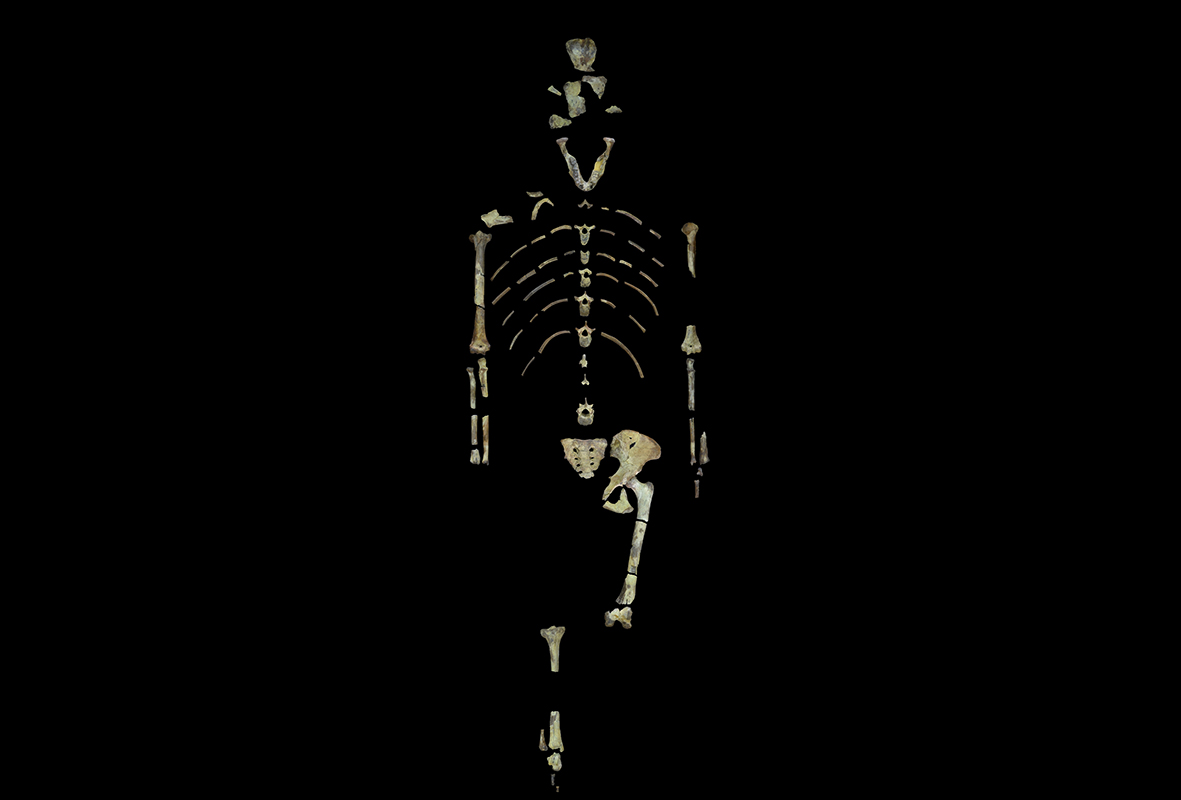

Lucy

In 1974, paleoanthropologists working in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia unearthed hundreds of bone fossils belonging to the hominin species Australopithecus afarensis. The bones represented about 40 percent of the skeleton of a female of that species, who lived approximately 3.2 million years ago. Scientists dubbed this skeleton "Lucy."

For decades, Lucy represented the only known skeleton of A.afarensis(several other bones belonging to members of the species were found in the 1970s, but more complete specimens weren't unearthed until the 1990s). Like modern humans, A.afarensis walked upright on two legs, but recent studies suggest that Lucy and her kin also used their load-bearing arms to climb trees, where they may have searched for food or hidden out from hungry predators.

Palace of Knossos, Crete

Located on the Greek island of Crete, the Palace of Knossos is a Bronze Age structure built by the Minoan civilization around 1950 B.C. The palace complex covers about 150,000 square feet (14,000 square meters) and, in ancient times, was surrounded by a sizeable town.

The Palace of Knossos became a well-known archaeological site in the early 20th century, when British archaeologist Arthur Evans led a team of researchers in the excavation and restoration of the ancient site (though the first excavations at Knossos were conducted in 1878 by an archaeologist from Crete). Evans and his team discovered that the first palace built on the site had been severely damaged and that another palace was built on top of it around 1700 B.C., according to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. The second palace stood until around 1450 B.C., when some kind of catastrophe (either a natural disaster or an enemy invasion) destroyed not only Knossos, but also other sites across Crete.

Knossos is perhaps best known for its colorful frescoes, many of which depict mythological creatures, marine wildlife and ceremonial scenes. The site also yielded many diverse examples of Minoan pottery, many of which are displayed at the nearby Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Sutton Hoo, England

Located in the east of England, Sutton Hoo is the site of several early medieval cemeteries, including an Anglo-Saxon ship burial — one of the most remarkable archaeological finds ever discovered in Great Britain.

The ship burial was unearthed in 1939, when Edith Pretty, then the landowner of the Sutton Hoo estate, asked archaeologist Basil Brown to investigate a large burial mound on her property. Inside the mound, Brown found the remains of an 86-foot-long (27 meters) ship loaded with treasures and, as he would discover, the skeleton of a long-dead Anglo-Saxon leader. Artifacts from the burial mound include an iron helmet, gold jewelry and silverware, many of which are on display at the British Museum.

Cave of Altamira

The prehistoric paintings that adorn the walls of the Cave of Altamira in Spain were discovered in 1879 by an amateur archaeologist and his young daughter. The Paleolithic drawings, which were made with charcoal and natural earth pigments, depict bison, aurochs (an extinct species of wild cattle), horses, deer and the outlines of human hands.

Scientists believe that most of the drawings were created between 14,000 and 18,500 years ago, though a recent study suggests that some of the artwork at Altamira was created about 35,600 years ago — at a time when humans were just starting to inhabit northern Europe.

Rapa Nui

Located in the southeast Pacific, Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, is best known as the home of approximately 1,000 giant "head" statues, or moai. There are an estimated 900 moai on Rapa Nui, which were carved and erected sometime between the 11th and 17th centuries A.D., according to UNESCO. The figures, which consist of oversized heads atop long torsos, range in height from 6 feet (2 meters) to over 30 feet (9 m), though one unfinished moai on the island is over 65 feet (20 m) tall.

The moai, and the ceremonial platforms (ahu) around which they typically stand, were built by a group of Eastern Polynesian settlers, who came to the island sometime around the first century A.D. The Rapa Nui people worshiped their ancestors and depended on these ancestral gods for protection and good fortune during life and the afterlife, according to the Easter Island Statue Project. Researchers believe that the moai were constructed as representations of these deified ancestors.

Antikythera Mechcanism

In 1900, a group of sponge divers in the Mediterranean Sea came across a 2,000-year-old shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera. The divers hauled many artifacts from the wreck, including three flat pieces of corroded bronze that are now known as the Antikythera Mechanism.

The rusty old device sat in storage at the National Archaeology Museum, Athens, until the 1950s, when Derek J. de Solla Price, a science historian from Yale University, took interest in the find. Price described the mechanism as an "ancient Greek computer," and other researchers have referred to the Antikythera Mechanism as an astronomical calculator. It's about the size of a shoebox and contains an intricate system of gears and a crank on the outside that controls the gears. The two faces of the device contain a series of dials, which researchers believe corresponded to a display of the sun, moon and planets.

While the ancient Greeks could have used the device to track the position of the sun, the phases of the moon and even the cycles of Greek athletic competitions, researchers aren't sure why ancient people would have needed such a complicated device to track those cycles. Recently, researchers have suggested that the Antikythera Mechanism was used as an instructional device — more of a novelty than a necessity.

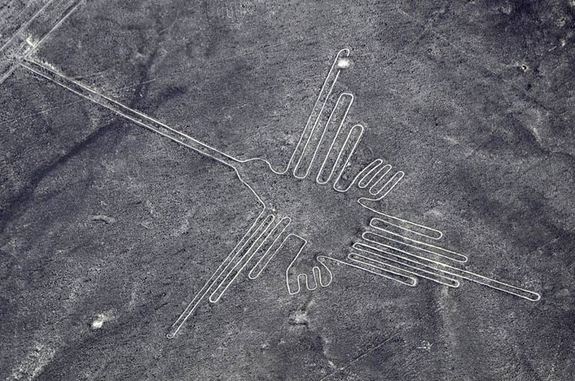

Nazca Lines

The Nazca Lines are geoglyphs (large designs produced on the ground) located on the coastal plateau of Peru. The designs, many of which were scratched on the ground or created with rocks, cover about 170 square miles (450 square kilometers). The oldest of the lines were made with rocks and date to 500 B.C., but the ancient Nazca people produced most of the designs between 200 B.C. and A.D. 500. Some of the Nazca Lines are simple geometric shapes, while others are in the shape of animals, like monkeys, birds and llamas.

The mysterious lines were never really "discovered," as they are visible from nearby foothills, and many people likely observed them before they were brought to the attention of the general public. Paul Kosok, a historian from the U.S., was the first researcher to seriously study the Nazca Lines in the 1940s. To this day, researchers aren't sure why the lines were made. However, there are a number of theories as to their possible uses, including those that suggest links to astronomy, religion and agriculture. [See Photos of the Mysterious Nazca Lines]

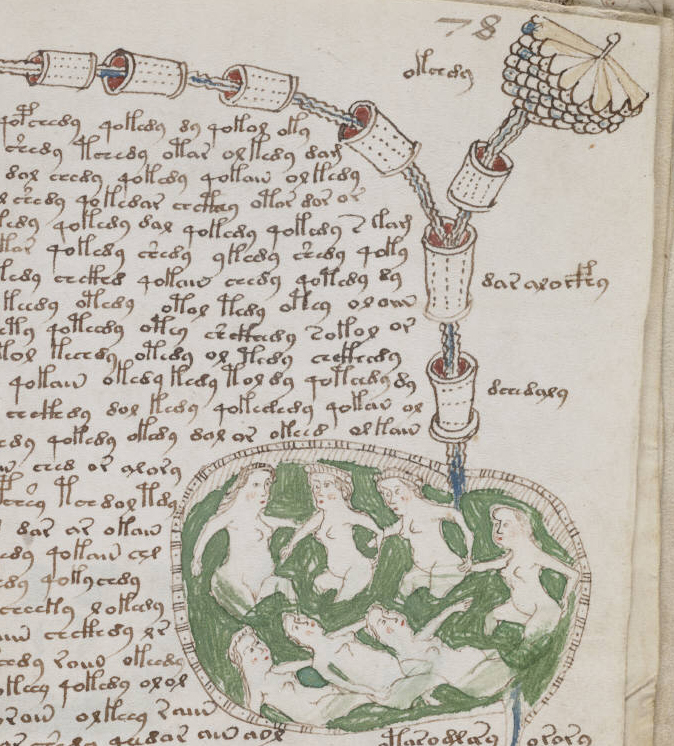

Voynich Manuscript

An antique dealer discovered the mysterious Voynich Manuscript in 1912 and immediately knew that he had stumbled upon something special — a book written in a language that no one can read. The 250-page book features a range of interesting images, from female nudes and Zodiac signs to drawings of medicinal plants.

Researchers believe that the book is about 600 years old and hails from Central Europe. One researcher who has studied the Voynich manuscript extensively believes that it is most likely a treatise on nature, written in an unknown Near Eastern or Asian Language. However, there are some scholars who believe that the manuscript is simply an elaborate hoax that has kept people guessing since the Renaissance. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Gobekli Tepe

Located in southern Turkey, near the modern-day city of Urfa, Göbekli Tepe is an archaeological site that dates back more than 11,000 years. Only a small portion of the site has been excavated since its discovery in 1963, but researchers believe that the structures found there may have been part of a prehistoric temple — perhaps the first temple ever constructed.

Göbekli Tepe's standout features are its T-shaped limestone blocks, which line the site's stone rings. The rings were built so that each was inside of the other and the largest has a diameter of 100 feet (30 m). Before building a new ring inside of a larger ring, ancient people would line the outer ring with the T-shaped blocks and then fill the outer ring with debris. The blocks were also carved with images of people and animals. While researchers aren't sure exactly what purpose all of these rings and blocks served, some suspect that the site attracted people from all over the Near East and served as a place of pilgrimage.

Staffordshire hoard

In 2009, a man in Staffordshire, England, quite literally struck gold while taking a stroll through the countryside. The man was using a metal detector in a recently ploughed field when he happened upon the largest Anglo Saxon treasure hoard ever discovered.

Archaeologists excavated the hoard, recovering more than 3,500 items made from gold, silver and other metals. Among these items are thousands of pieces of garnet cloisonné jewelry (gold items with inlaid garnet, a red gemstone), golden sword pommels and crosses. Most of the artifacts that make up the hoard are "martial" in nature, or have something to do with warfare, and none of the items are domestic goods, like cups or silverware. This leads researchers to believe that the treasure may have been part of a "death duty," or a collection of valuable gifts that were given to a king upon the death of one of his noblemen.

Most of the items in the Staffordshire hoard date back to the seventh century A.D., and many of the treasures are on display at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in the U.K.

Provincial pyramids of Egypt

You've heard of the Great Pyramid of Giza, but what about the step pyramid of Edfu? This ancient structure is about 4,600 years old, making it at least a few decades older than the famous pyramid at Giza.

The once 43-foot-tall (13 meters) step pyramid is one of seven "provincial" pyramids constructed by either pharaoh Huni or Snefru sometime between 2635 and 2590 B.C. These early pyramids are found throughout central and southern Egypt near what were once major settlements. Unlike the pyramids at Giza, the step pyramids do not contain internal chambers and weren't used for burial. In fact, researchers aren't sure what their primary purpose was.

Scholars knew about the pyramid at Edfu long before it was first excavated in 2010. However, recent efforts by archaeologists from the University of Chicago are the first to explore in-depth the reasons for the pyramid's construction and subsequent abandonment not long thereafter.

Madaba Map

The Madaba map is the oldest surviving map of the Holy Land (particularly Jerusalem) and is part of a floor mosaic in the Byzantine church of Saint George in Madaba, Jordan. The map was uncovered during renovations at the church in 1884 and dates to somewhere between 560 and 565 A.D. [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

While the map originally depicted a large swath of the Middle East, from southern Syria to central Egypt, much of the mosaic map was already destroyed when it was first uncovered. However, the part of the map depicting Jerusalem remained in tact and includes an oval-shaped walled city with six gates, 21 towers and several dozen buildings and structures.

Visitors to Madaba can see the map in person, and a copy of the ancient map is also kept at the Archaeological Institute at Göttingen University in Germany.

The grave of Richard III

After centuries of speculation, the grave of King Richard III was finally unearthed in 2012 by archaeologists at the University of Leicester in England. The king, who was immortalized (for better or for worse) in Shakespeare's play "Richard III," died in battle in 1485. Rather than a regal funeral, King Richard's body was reportedly interred at the church of the Grey Friars in Leicester, the location of which was lost to history.

But using historical records, archaeologists were able to narrow down the former location of the church and recover the bones of the late king. In 2015, Richard III was reburied in a marble tomb next to the altar in Leicester Cathedral.