'Immigration Act of 1917' Turns 100: America's Long History of Immigration Prejudice

One hundred years ago today (Feb. 5), Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1917, the first legislation to dramatically limit immigration into the U.S. It introduced rulings that singled out specific countries and ethnicities, and included conditions that favored privilege over need.

While many people view immigration as a cornerstone of America's journey and continued success as a country — a position outlined by White House representatives under President Barack Obama — sweeping restrictions such as those put forward in 1917 also shaped the United States' immigration story.

Decades after the 1917 act became law, its guidelines for inhibiting immigration persisted. And its legacy reverberated recently, when President Donald Trump issued a Jan. 27 executive order temporarily halting the acceptance of refugees from Syria, and forbidding people from several predominantly Muslim countries from entering the U.S. [Refugee Crisis: Why There's No Science to Resettlement]

The Immigration Act of 1917, also known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act, prohibited immigration from any country that was on or adjacent to Asia but was "not owned by the U.S.," according to a summary shared online by the University of Washington Bothell Library (UWBL). The Philippines was not included in the ban because it was a U.S. territory at the time, and Japan was excluded for diplomatic reasons.

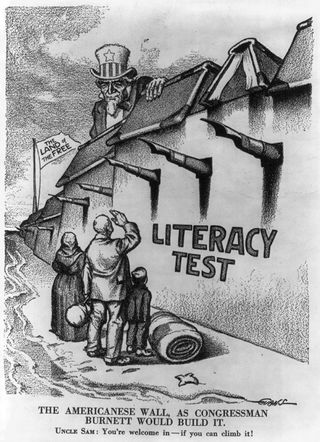

The act also stated that all immigrants over age 16 would be required to pass a literacy test, demonstrating that they could read "not less than 30 nor more than 40" words in English or in "some other language or dialect." Further prohibitions expanded an existing list of "undesirables," adding epileptics, alcoholics, political radicals, anarchists, criminals, people suffering from contagious diseases or with mental or physical disabilities, and people who were merely poor, UWBL explained.

"A radical departure"

First proposed in 1915, the legislation was vetoed twice by then-President Woodrow Wilson, who declared in a message issued Jan. 28, 1915, to the House of Representatives that such a bill would be "a radical departure from the traditional and long-established policy of this country" to welcome immigrants. Congress overturned his second veto on Feb. 5, 1917.

The ban on people from most Asian countries was the first to target a specific geographical region, expanding on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 — the first legislation to deny immigration to a specific ethnic group. The act's momentum was driven by nationalist fervor, the propaganda machines of World War I and the anti-immigrant "100 percent Americanism" movement, according to Mae Ngai, a professor of history and Asian American studies at Columbia University.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It also reflected prevailing negative attitudes in the U.S. toward Chinese immigrants, and extended that prejudice to also exclude immigrants from South Asia, Rebecca Kobrin, an associate professor of history at Columbia University, told Live Science.

"This was a big move for restriction of immigration. It marked the move of America to think of itself as a nation defined by race, and it inscribed those racial hierarchies into law," Kobrin said. "There has always been demonization of groups in our history. At the time, Asians were seen as a hallmark of 'the other.'"

These immigration laws were paralleled by other forms of legalized racial discrimination across the country, Ngai told Live Science in an email.

"Asians suffered from state laws excluding them from various professions and occupations — such as teaching and commercial fishing — and from owning agricultural property," Ngai said.

The literacy test included in the Immigration Act of 1917 was also unfair because it offered immigrants a limited selection of languages to prove their proficiency, according to Kobrin. If an immigrant's native tongue didn't appear on that list, he or she would have been considered illiterate and denied entry, Kobrin said. [20 Startling Facts about American Society and Culture]

As harsh as the 1917 measures were, for many members of Congress, the restrictions didn't go far enough, and even stricter legislation followed, María Cristina García, a professor of American studies at Cornell University, told Live Science in an email.

From 1921 through 1924, a series of quotas drastically reduced European immigration into the U.S., cracking down more severely on countries in eastern and southern Europe, who were not as well established in American communities as were people from western and northern Europe, García said. Following the Immigration Act of 1924 (also called the Johnson-Reed Act), "Germany's quota stood at over 51,000, while Greece and Albania had quotas of 100 each," García said.

And at the height of the anti-communist "Red Scare" during the 1950s, European immigrants suspected of communist sympathies or activities were punitively targeted with criminal charges and deportation measures, Ngai said.

Righting a wrong

Immigration quotas shaped by race remained in place until the Hart-Celler Immigration Act of 1965, which abolished quotas and prioritized uniting families by granting naturalized immigrants the ability to sponsor relatives in their native lands. When President Lyndon Johnson signed it into law, he praised it as correcting "a cruel and enduring wrong in the conduct of the American nation," according to the Center for Immigration Studies.

However, Trump's Jan. 27 executive order appeared to revisit an earlier time, when America's perception of immigrants was less welcoming. It suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for 120 days; prohibited entry to Syrian refugees indefinitely; suspended entry for 90 days to immigrants and nonimmigrants from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen (countries that were identified later by the Department of Homeland Security in a fact sheet); and limited refugee admission to 50,000 people for the duration of 2017's fiscal year. This order was seen by many as prejudicial and racially motivated, The Atlantic reported.

Laws that legitimize discrimination on racial grounds can send a troubling message, fueling public fear that can spark violence and hate crimes toward targeted groups, Ngai told Live Science.

"Trump's executive order, and the stereotypes and discourses that circulated during the 2016 presidential election, more generally, are rooted in century-long conversations about who is 'worthy' of admission to the United States," García explained.

"However, history also teaches us that, while some Americans are fearful, others are welcoming, and they challenge draconian immigration policies if they violate our most deeply held convictions about justice and equal opportunity," García said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.