The mystery of the dwarf planet Ceres' lonely ice volcano may have just been solved.

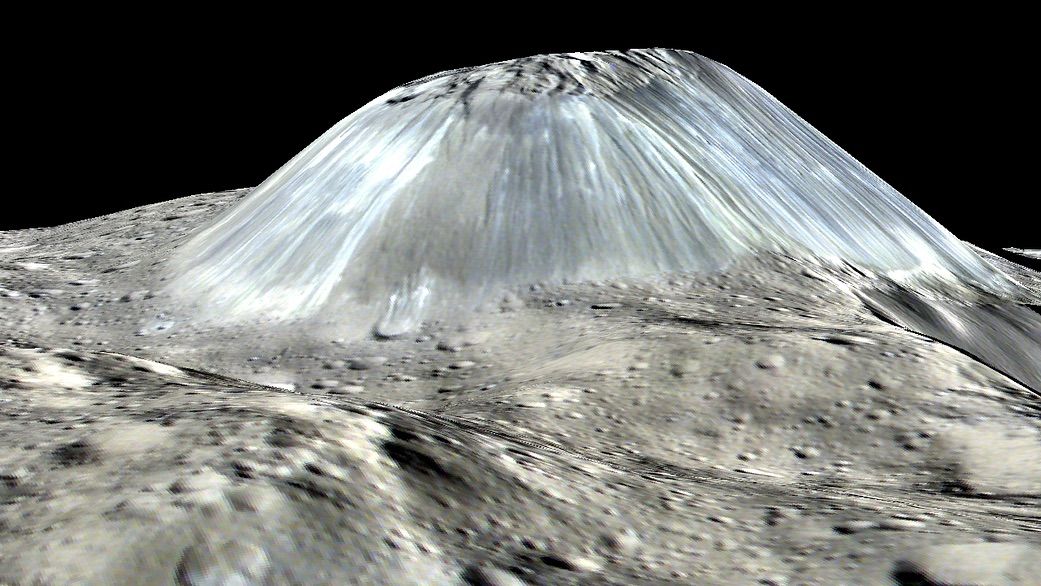

NASA's Dawn probe discovered the 2.5-mile-high (4 kilometers) cryovolcano, named Ahuna Mons, in 2015. There's nothing else remotely like it on the 590-mile-wide (950 km) Ceres — a fact that has had scientists scratching their heads.

"Imagine if there was just one volcano on all of Earth," Michael Sori, of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, said in a statement. "That would be puzzling." [The Dwarf Planet Ceres in Photos]

Ahuna Mons could simply be a one-of-a-kind feature. But new research by Sori and his colleagues suggests another possible answer: Ahuna Mons may have once had company, older cryovolcanoes that flattened out and disappeared over the eons via a process called "viscous relaxation."

Viscous relaxation means that many solids on a planetary surface will flow, given enough time. Earth's mountains don't relax in an appreciable way, because they're made of rock. But Ahuna Mons has a lot of water ice mixed in and is therefore a relaxation candidate, Sori said. (Think of the flowing glaciers on Earth.)

So Sori and his colleagues used computer simulations to model how Ahuna Mons would relax over time. They found that such relaxation would occur only if the cryovolcano were made of at least 40 percent water ice. At this composition, Ahuna Mons should be flattening out at the rate of about 33 feet to 165 feet (10 to 50 meters) per 1 million years, the researchers report in a new study, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Such a relaxation rate is sufficient to wipe out a large Ceres cryovolcano in hundreds of millions to a few billion years. So it's possible that Ahuna Mons once had older brothers and sisters, which have since vanished into Ceres' frigid surface, Sori said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Ahuna Mons is at most 200 million years old," Sori said. "It just hasn't had time to deform."

Sori and his team plan to search for signs of Ceres' lost cryovolcanoes (which would spew icy material rather than molten rock) in other images captured by Dawn. The probe has been studying Ceres — the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter — from orbit since March 2015.

Such work could inform scientists' understanding of cryovolcanoes throughout the solar system, said Kelsi Singer, a postdoctoral researcher at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, who was not involved with the new study. (Cryovolcanoes are suspected to occur on a number of different bodies, such as Pluto, Pluto's moon Charon, the Neptune moon Triton and Saturn's giant satellite Titan.)

"It would be fun to check some of the other features that are potentially older domes on Ceres to see if they fit in with the theory of how the shapes should viscously evolve over time," Singer said in the same statement. "Because all of the putative cryovolcanic features on other worlds are different, I think this helps to expand our inventory of what is possible."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.