478-Million-Year-Old Spiky Slug Solves Long-Held Mollusk Mystery

A tiny, hat-like shell that adorns a 478-million-year-old spiky slug is helping scientists figure out how mollusks evolved over the ages, according to a new study.

The newly identified species solves a decades-old puzzle. Mollusks are a diverse group of invertebrates that includes both water and land animals, from the clever octopus to the slow snail. However, it's unclear whether mollusks evolved from an ancestor with no shell, one shell or two shells, the researchers said.

Now, the scientists can confidently say that the ancestor of all mollusks likely had one shell, just like the newfound species, they said. [See images of the ancient "hat"-wearing slug]

The specimens — seven in all — were discovered in the late 2000s by Mohamed 'Ou Said' Ben Moula, a self-taught fossil collector who has uncovered hundreds, if not thousands, of specimens with fossilized soft tissues in Morocco's Fezouata Biota. Ben Moula has a working relationship with paleontologists at Yale University, and shipped the fossils to Yale, in Connecticut, so they could be studied.

Two of the specimens — one adult and one juvenile — were complete, allowing the researchers to examine their anatomy in detail.

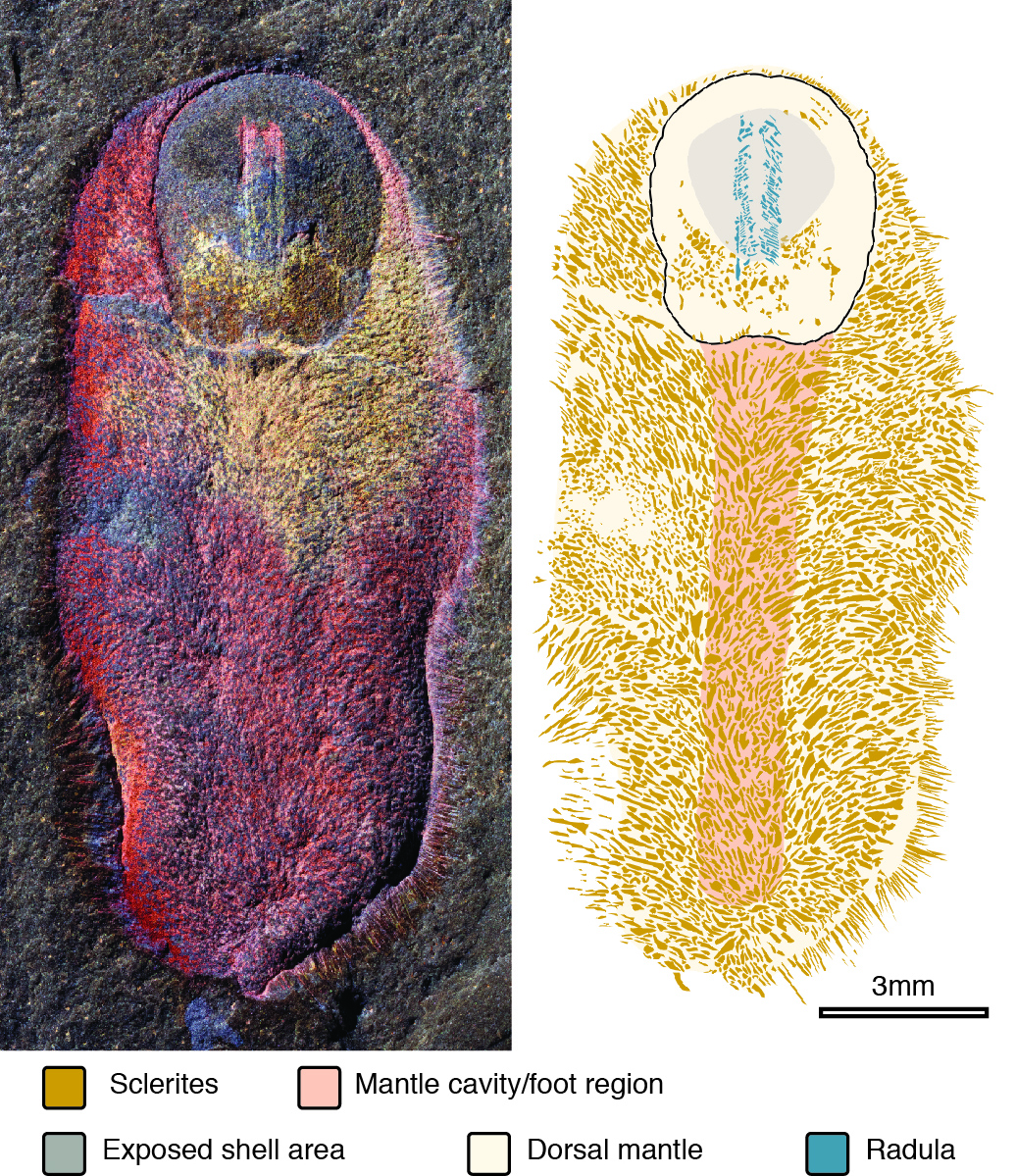

"I describe them as an armored, spiny slug with one single shell at the head end," said the study's co-lead researcher, Luke Parry, a doctoral student in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol in England.

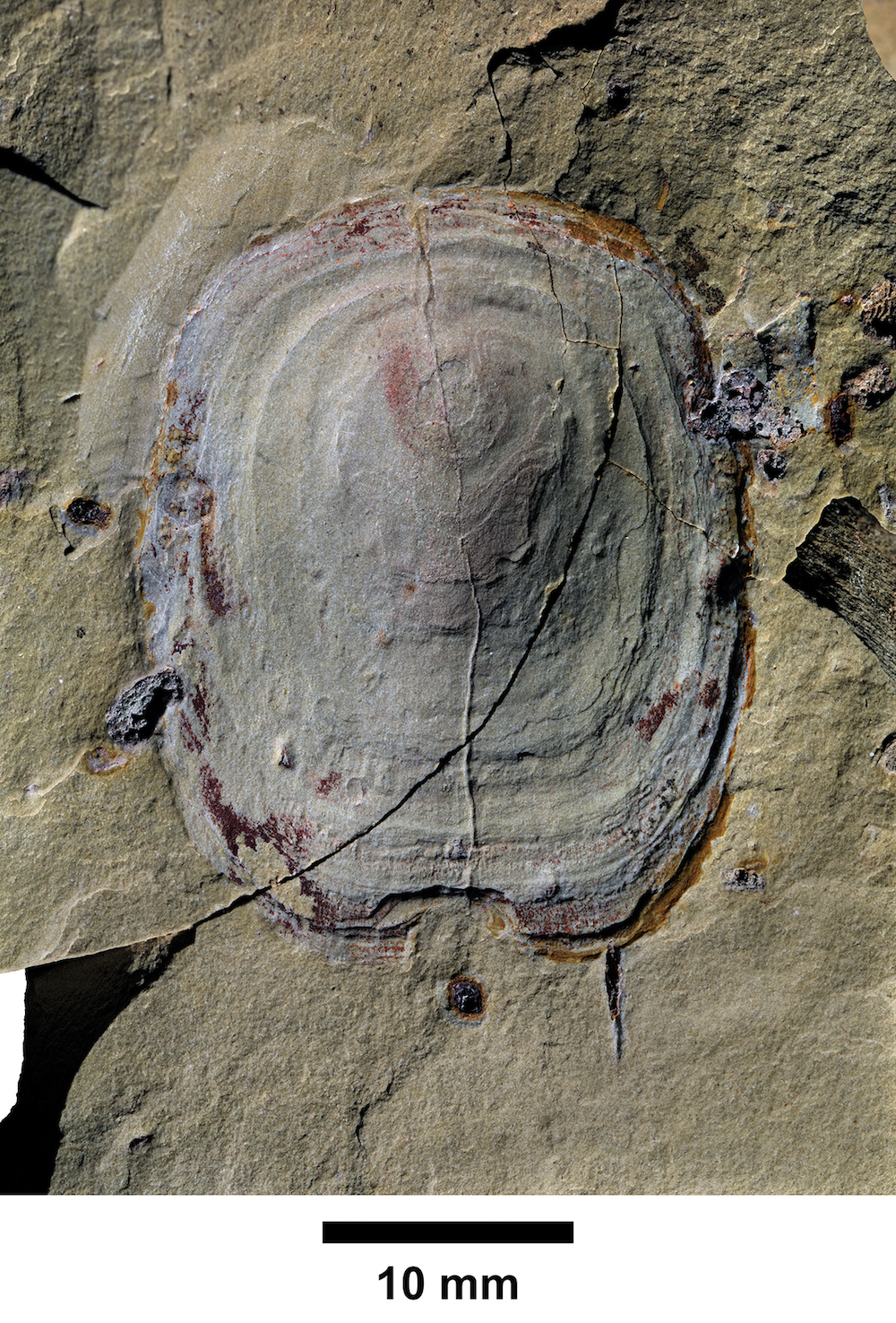

The researchers named the newfound mollusk Calvapilosa kroegeri. The creature's head plate was densely covered with spikes, which inspired its genus name, because "calva" and "pilosus" are Latin for "scalp" and "hairy," respectively, the researchers said.The species name honors Björn Kröger, a paleontologist who discovered the first C. kroegeri specimen in the material that Ben Moula sent to the Yale collections.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tiny teeth

Amazingly, some of the roughly 4-inch-long (10 centimeters) C. kroegeri specimens had preserved radula — "this conveyor belt of rasping teeth that's in the pharynx," Parry told Live Science. "It's underneath the shell, but because the shell has been dissolved away [in the fossil], you can see all of these hundreds and hundreds of tiny teeth pressed up against the shell."

Some mollusks, including snails, use the radula to rake up food, such as algae off of rocks, Parry added. Because no other group of animals has a radula, its presence indicated that the newfound species was a mollusk, he said.

Researchers have found other fossils of animals that look like mollusks. However, they haven't been able to definitively label them as such, because these fossils don't have preserved characteristics that are as unique as a radula, Parry said.

The radula finding is extraordinary, as it helps researchers label similar fossil animals as mollusks, said study senior researcher Peter Van Roy, a paleontologist at Yale University.

"Calvapilosa, in possessing a radula, unequivocally shows that other fossils like Halkieria [an ancient slug-like creature with two shell 'hats' found in Greenland] and Orthrozanclus [a spiny critter found in Canada's Burgess Shale deposit] belong to the molluskan … group," Van Roy told Live Science in an email. "The affinities of these animals were previously debated."

After studying C. kroegeri's features, the researchers did an analysis to decipher the mollusk family tree. The newfound mollusk was the most primitive member of the lineage leading to chitons, modern-day marine mollusks that sport eight shell plates as well as spines that are similar to those found on C. kroegeri, the researchers said. [Photos: Trove of Marine Fossils Discovered in Morocco]

Interestingly, whereas some mollusks, such as chitons, evolved to have more shells, others, such as aplacophorans (a group of modern worm-like animals), evolved to have no shells at all, the researchers said.

"If we trace back the evolution of chitons, we can see that the number of their shells has increased with time," study co-lead researcher Jakob Vinther, a senior lecturer of macroevolution at the University of Bristol, said in a statement. "It is therefore likely that the ancestor to all mollusks was single-shelled and covered in bristle-like spines, not dissimilar to Calvapilosa kroegeri."

The study was published online today (Feb. 6) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.